An Introduction to Louisiana French

Louisiana French is a collection of varieties spoken by Native Americans, Africans, Acadians and Europeans since the 18th century.

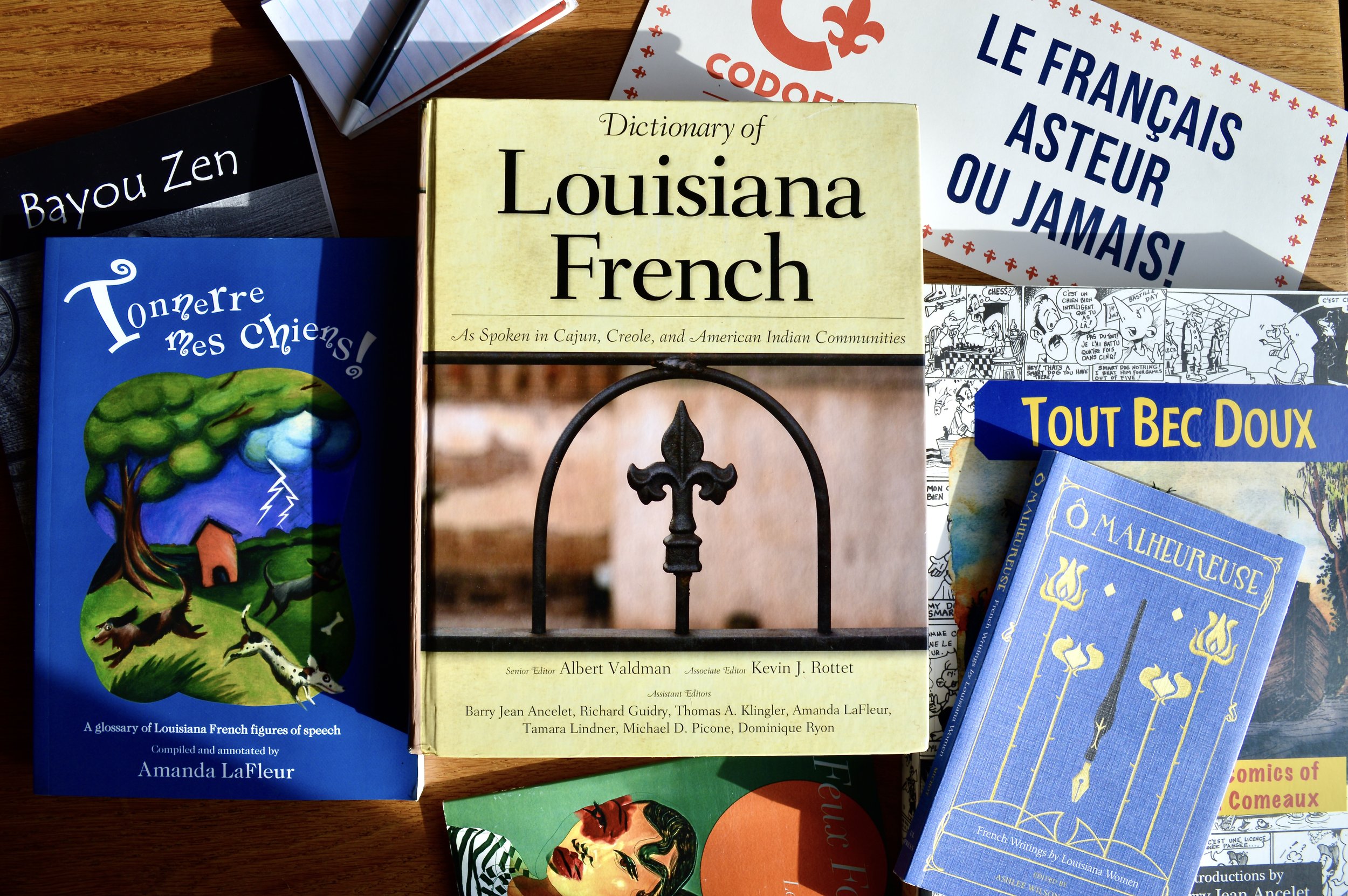

The “Dictionary of Louisiana French: As Spoken in Cajun, Creole, and American Indian Communities” serves as a valuable resource for francophones wishing to learn. Jonathan Olivier/Télé-Louisiane

By Jonathan Olivier

It was always those little phrases my mom or dad would utter that stuck with me the most. Viens manger or ferme la porte. Scattered throughout their English were words rooted in Louisiana French, the byproduct of their upbringings—their parents are native speakers of French, while my mom’s mother also grew up with Louisiana Creole.

Yet, for the majority of my life French only played a minor role—the result of decades of Americanization, economic changes in Louisiana, and the state’s 1921 constitution that allowed only English to be used in classrooms. A heritage and linguistic chain had been severed, one that linked me to my first francophone ancestors in North America who came in the 1600s to Nova Scotia, Canada, in the region they called Acadia.

The journey to reclaiming my family’s heritage language has been a long one. I have taken classes in high school, college and participated in French immersion in Canada. I traveled to Quebec and New Brunswick. I began to hardly speak English to my grandparents, embracing and better understanding the French of my family, of my home. In a region now dominated by English, I have to work at it every day. I make mistakes, then learn from them. At times, it feels more like work than reconnecting with my past. And I’d imagine this is true for most folks who have taken that step toward reclaiming a heritage language.

Although, at other points, I forget the grind and the pressure to hold on to French as the number of native speakers continues to decline. I don’t worry so much about the mistakes I make. Speaking French feels effortless. The language of my ancestors opens up doors I didn’t know were there. Ideas, opportunities and friends arrive in my life that otherwise would’ve been unknown to me. For me, speaking French has evolved past a journey of reclamation, but now it’s an integral part of my existence, a powerful piece of my identity.

For those wanting to take the first step to reconnecting with French, or even for those who are just curious about it, this guide is meant to provide you with an introduction to several aspects of it. This article is not exhaustive at all, meaning I’ve left out more than I could include. But I hope that this provides you with a start, or perhaps even inspiration to keep going in your journey to reclaim this heritage language as your own.

What is Louisiana French?

Louisiana French, also commonly called Cajun French, is an umbrella term for a collection of varieties of French that was first spoken in the region by francophone groups such as colonial French settlers, Canadians, Haitian Creoles and Acadians. French, the dominant language of Louisiana for many generations beginning in the 18th century, was also adopted by many of Louisiana’s Native American groups, enslaved Africans and free people of color, as well as German, Spanish and English immigrants.

Today, the predominant populations that continue to speak French as their first language consist of Bayou Indians (Native Americans of Lafourche and Terrebonne parishes), Creoles, and Cajuns. All three of these groups descend to varying extents from the founding peoples of Louisiana.

Over the decades, French in Louisiana was shaped by these different ethnic groups. For example, there are many indigenous elements in Louisiana’s lexicon, such as chaoui (raccoon), a Choctaw word, or plaquemine (persimmon), from an Algonquian language. The words gombo and févi (both can refer to okra) are derived from African peoples and lagniappe comes from Spanish in South America.

Other notable features are archaic structures that Louisianans have retained but that have mostly disappeared from today’s international French. For example, chevrette (shrimp) is an older French word that remained in Louisiana due to isolation while in France today people use crevette, more recently adopted from the Normans. Still, Louisianans adapted words to refer to new inventions like cars, which in Louisiana and Quebec is char and in France it is voiture.

Despite these few lexical variations, French in Louisiana is mutually intelligible with other varieties of French across the francophone world. After all, the French as it’s spoken today in France is only one dialect of the language, just as American English varieties differ slightly from British English.

A Language Continuum

In geographic areas where French has existed alongside Louisiana Creole, there is the notion of a continuum of French and its related varieties, which includes: Louisiana French, Louisiana Creole and international French. A continuum implies some sort of structure involving elements that are similar yet markedly different at the two poles. In this case, it’s easy to think about the three elements existing on a linear plane, with international French and Louisiana Creole at separate ends, then Louisiana French in the middle. These two extreme poles are different on the morphosyntactic level while there is much overlap on the lexical level between Louisiana French and Louisiana Creole. These similarities and differences are incredibly important in Louisiana, where different speech communities regularly interact with one another.

People can be placed on the continuum, depending on the language or variety of French they speak. However, due to the interaction between speech communities, people often have the ability to move back and forth along the continuum depending on who they are speaking with. For example, a French speaker might be able to move more toward Creole on the spectrum if he or she regularly interacts with Creole speakers. This tactic allows different speech communities to effectively communicate.

Although, at one time, Louisiana Creole was categorized as a dialect of French, it is in fact its own language given its unique syntax and grammar, despite its lexical similarities with French. Louisiana’s speech community is further complicated and enriched by the fact that Louisiana Creole is spoken not only by people who identify as Creole but also by many Cajuns. While Louisianans may refer to the language they speak as Cajun, Creole, Cajun French, Indian French, Houma French, Creole French, or just French, linguists increasingly use the terms Louisiana Creole or Kouri-Vini, and Louisiana French, in an effort to more accurately identify these two languages within Louisiana’s linguistic continuum.

Variations of French in Louisiana

Herb Wiltz, pictured here in episode 10 of La Veillée, speaks French and Louisiana Creole. Drake LeBlanc/Télé-Louisiane

There are several varieties of French in Louisiana that differ due to an array of factors like geographic location, age, education or even language attrition. Some francophones in southeast Louisiana, particularly in south Lafourche Parish, utilize an aspirated “h” when pronouncing “j” or “g” (j’ai été sounds like h’ai été). Someone might use the word grouiller to mean “to move” to another home, while others will say déménager or even “move,” borrowed from English. In Avoyelles and Lafourche parishes, it’s common for speakers to express “what” by saying qui while other regions of Louisiana employ quoi.

Professor emeritus at the University of Indiana Albert Valdman, in his study “Standardization or laissez-faire in linguistic revitalization,” included an example of a native speaker that, in one paragraph, used five different ways to express they, or the third person present indicative verb form: eux-autres, ça, ils, eusse, and ils with -ont.

Mais sho, eux-autres serait contents, tu les appelle ‘oir, parce que ça travaille tard, eusse a un grand jardin en arrière, et ils travaillont tard, des fois ils sont tard dans la maison. [Well sure, they would be happy, you call them and see, because they work late, they have a big garden in back, and they work late, sometimes they’re in late.]

The study displayed that different age groups tended to stick to different forms of the third person present indicative verb form. For example, 25 percent of people older than 55 tended to use ils, while only one percent of people under 30 used ils—instead, 77 percent of them opted for eusse.

Due to this variation, linguists don’t exactly have a neat definition for French in Louisiana. Instead, it’s best understood as a collection of different varieties that are spoken across the state. Even still, these varieties share a lot in common, so below are some examples that make French in Louisiana unique.

Lexical Items

Ruby and Raymond Danos, pictured here in the sixth episode of La Veillée, are from Cutoff, Louisiana, where they learned to speak French as children at home. Drake LeBlanc/Télé-Louisiane

A lexical item is a word or a sequence of words. Due to Louisiana’s linguistic diversity, its French contains some lexical items unique to the region—although much more are well known in Canada, France or throughout la francophonie. Other lexical items are quite common in French, although they have taken a different meaning in Louisiana due to its isolation from other francophone regions. Here are a few examples:

Un chaoui (indigenous origin)

English: Raccoon

International French: Un raton laveur

Asteur (common in Canada and parts of France)

English: Now

International French: Maintenant

Un char (common in Canada)

English: Car

International French: Une voiture

Une banquette

English: Sidewalk

International French: Un trottoir

Une piastre (common in Canada)

English: Dollar

International French: Un dollar

Une chevrette

English: Shrimp

International French: Une crevette

Un plaquemine (indigenous origin)

English: Persimmon

International French: Un kaki

Des souliers

English: Shoes

International French: Des chaussures

Espérer

English: To wait

International French: Attendre (in France, espérer means “to hope”)

Regional Grammatical Structure

In Louisiana, the grammatical structure, or arrangement of words, can be varied and also unique. While second language learners of French are often quick to pick up lexical items like nouns, it can be harder to incorporate more complex grammatical structures. If you talk to any native speaker of French in Louisiana, chances are you’ll hear these four structures often.

Être après

In international French, the present progressive is être en train de, such as je suis en train de faire quelque chose (I am doing something). However, in Louisiana, this form is être après, such as je suis après faire quelque chose.

Avoir pour

This is a common way to express “to have to” in Louisiana. While other ways of expressing a necessity are also common by using words such as devoir, il faut or avoir besoin, in Louisiana, avoir pour is pretty unique. For example, someone might say, J’ai pour travailler aujourd’hui (I have to work today).

Article-Preposition Contractions

With prepositions, it’s standard in international French to write and say de le as du, or de les as des. Yet, in Louisiana, you’ll often hear speakers avoid these contractions. So, one might say, C’est à cause de le froid j’ai resté dedans la maison (I stayed inside because of the cold).

Subject Pronouns

Typically, native speakers of French in Louisiana follow the same subject pronoun patterns as international French, with a few exceptions. For example, the international French vous is hardly used in Louisiana—only in very formal situations. In the below examples, conjugations that differ from international French are noted.

Je (i)

Tu (you)

Vous (you, used rarely and only in very formal situations)

Il (he)

Elle (she, sometimes pronounced/written as alle)

Nous-autres, On (we)

The more colloquial expression of “we,” expressed by on, has by and large replaced nous in Louisiana. Yet, nous-autres is often used in conjunction with on. For example, Nous-autres, on était dans le clos un tas des années passées. (We were in the fields a lot back then.)

Vous-autres (you plural)

This subject pronoun uses the same verb form as the third person singular il. For example, Vous-autres va à la messe ? (Y’all are going to mass?)

Ils (they, often used to express men and women)

Elles (they, this feminine form is not often used)

Ça, eux-autres, eusse (they)

Eusse is common in southeast Louisiana, such as in Terrebonne and Lafourche parishes. However, it isn’t as common in other parts of Louisiana. While ça and eux-autres are typically used throughout the French-speaking region of the state. These three are typically conjugated using the third person singular verb form. For example, Eux-autres a deux garçons. Mais ça voulait une tite fille itou. (They have two boys. But they wanted a little girl too.)

How to Learn

Abraham Parfait of the United Houma Nation, pictured here in the fifth episode of La Veillée, speaks what people in his community call Houma French or Indian French. Drake LeBlanc/Télé-Louisiane

There are plenty of ways to learn. Online classes taught by local experts are available, and texts that have been compiled by linguists offer valuable information about the dialect. And, of course, one of the best ways to practice is to find a native speaker to learn directly from them. If they’ll allow it, record your conversation and transcribe it, which functions as an intimate way to learn. Below, you’ll find resources to get you started on your journey to learning.

Videos

Les Adventures de Boudini et Ses Amis, a cartoon series in French, produced by Crele Cartoon Company with Télé-Louisiane for Louisiana Public Broadcasting (LPB), which is perfect for beginners or children.

La Veillée, a fifteen-minute weekly news magazine produced by Télé-Louisiane and LPB.

Le Louisianiste, Télé-Louisiane’s newest podcast with a focus on native speakers of French.

Le français louisianais: quoi c’est ça ?, a YouTube video produced by Télé-Louisiane that expains the basics of French in Louisiana.

Kirby Jambon’s French lessons, a series lessons made by Acadiana French teacher Kirby Jambon.

Classes and online databases

Classes hosted by Alliance Française de Lafayette, taught by David Cheramie and Ryan Langley.

Online resources provided by the Department of French Studies at LSU.

Louisiana French Oral Histories, an oral history project complete with interviews of native French speakers and corresponding transcriptions, compiled by the Department of French Studies at LSU.

Memories of Terrebonne, an oral history collection from Terrebonne Parish.

French Tables, which are informal gatherings where francophones get together and chat, are held around the state. This list has been compiled by the Council for the Development of French in Louisiana.

Cajun French Virtual Table Française, a Facebook group dedicated to French.

Cajun French Video Lessons, a Facebook group that posts videos.

Books

Tonnerre mes chiens! A glossary of Louisiana French by Amanda LaFleur

Dictionary of Louisiana French: As Spoken in Cajun, Creole, and American Indian Communities by Albert Valdman et. al

Cajun French Dictionary and Phrasebook by Jennifer Gipson and Clint Bruce

Sources:

Ancelet, B. J. (1988). "A perspective on teaching the “problem language” in Louisiana.” The French Review, 61,

345-356.

Ancelet, B. J. (2007). “Negotiating the mainstream: The Creoles and Cajuns in Louisiana.” The French Review,

80, 1235-1255.

Blyth, C. (1997). “The Sociolinguistic Situation of Cajun French: The Effects of Language Shift and Language

Loss.” In A. Valdman (Ed.), French and Creole in Louisiana (pp. 25-46). New York: Plenum Press.

Brown, B. (1993). “The social consequences of writing Louisiana French.” Language in Society, 22, 67-101

Dajko, Nathalie (2012). “Sociolinguistics of Ethnicity in Francophone Louisiana.” Language and Linguistics

Compass, 6, 279-295.

Dajko, Nathalie; Carmichael, Katie (2014). “But qui c’est la différence ? Discourse markers in Louisiana French:

The case of but vs. mais.” Language in Society, 43, 159-183.

Valdman, Albert (2000). "Standardization or laissez-faire in linguistic revitalization: The case of Cajun French.”

Indiana University Working Papers in Linguistics 2: The CVC of Sociolinguistics: Contact, Variation, and

Culture, 127-138.

Valdman, Albert; Picone, Michael D (2005). “La situation du français en Louisiane.” In A. Valdman et. al, Le

Français en Amérique du Nord: État présent (pp. 143-165). Les Presses de l’Université Laval.