John Bel Edwards inaugurates new home of École Pointe-au-Chien

In August, the school opened its doors in a temporary location as it awaits renovations on its permanent site at the former Pointe-aux-Chênes Elementary.

In August, the school opened its doors in a temporary location as it awaits renovations on its permanent site at the former Pointe-aux-Chênes Elementary.

Gov. John Bel Edwards after his remarks at École Pointe-au-Chien on Tuesday, November 7, 2023. Wayan Barre/Télé-Louisiane

By Jonathan Olivier

Gov. John Bel Edwards, at an inauguration event on Tuesday for École Pointe-au-Chien, stressed that now is the time to take steps to preserve and advance French in Louisiana before the last generation of native speakers fades away.

“These kids come here and they’re learning French, and they go home to parents that don’t speak French,” Edwards said. “But the French is being reinforced by the grandparents. If we had gone one more generation, it would be exponentially harder, and probably would never have happened, that we would hang on to this.”

Edwards visited the small community of Pointe-aux-Chênes on Tuesday for an official inauguration of the schools’ new location in a Knights of Columbus building. The public school, the country’s first French immersion program serving a predominantly Indigenous population, was created through legislative action in 2022. The move came after the public outcry resulting from the closure of Pointe-aux-Chênes Elementary in May 2021, and an effort led by the Pointe-au-Chien Indian Tribe in collaboration with partners including Télé-Louisiane, the French Consulate, and the Louisiana Department of Education. The school is now governed by an independent state board.

Since signing the bill into law, Edwards has voiced support for the school and the historic move spearheaded by his administration. At the event Tuesday, he reiterated his commitment to French in the state as a way to strengthen Louisiana’s economy, culture and small communities.

“They will do better overall than kids in non French immersion schools—and you all are going to see this,” he said. “As a result, this school is going to pay dividends for years to come.”

Wayan Barre/Télé-Louisiane

In addition to Edwards, French Consul Rodolphe Sambou, school Board President and Télé-Louisiane CEO Will McGrew, and Rep. Mike Huval, R-Breaux Bridge, also shared remarks at the inauguration ceremony to an audience of Pointe-au-Chien tribal members, parents, state officials, francophone advocates and other community members.

Christine Verdin, executive director of the school, noted in her remarks that École Pointe-au-Chien has been temporarily housed in the Vision Christian Center in Bourg since August, and after moving to the KC Hall around Thanksgiving, it will remain there until the 2025-2026 school year when renovations are expected to be completed on the former Pointe-aux-Chênes Elementary building.

Verdin said they have enrolled more students since the beginning of the academic year and are working to acquire a bus, among other steps to ensure longevity of the program in the community. She noted that in August, her students didn’t know how to speak French at all—now, they use the language every day.

“To see them singing French, saying the pledge in French, and they speak to each other in French, it’s really something very positive,” she said. “And they go home speaking French.”

La Veillée returns for second season on LPB

Each week, Télé-Louisiane highlights different aspects of Louisiana culture and way of life in the only Louisiana French TV news show.

Each week, Télé-Louisiane highlights different aspects of Louisiana culture and way of life in the only Louisiana French TV news show.

Drake LeBlanc/Télé-Louisiane

By Jonathan Olivier

The second season of La Veillée premiered on October 5 on Louisiana Public Broadcasting (LPB). The premiere episode focused on the opening of École Pointe-au-Chien and the school's effort to teach the region’s local French dialect.

The series airs every Thursday at 7:45 p.m. in Louisiana French with English subtitles. It’s part of LPB’s ongoing commitment to showcasing Louisiana’s unique French culture and heritage. “The great viewer response we receive to this series underscores the high interest Louisianans have to the French language, and also to our French history,” said Jason Viso, LPB Director of Programming. “But the interest in La Veillée transcends our Louisiana audience. Thanks to streaming, it has put Louisiana’s French culture in the spotlight throughout the Francophone world, especially in France and Canada.”

La Veillée’s second season will again cover unique and compelling stories across Louisiana. After covering École Pointe-au-Chien in episode 1, the second episode focused on the unique Creole language and culture of the Creoles of Pointe Coupée Parish.

Drake LeBlanc/Télé-Louisiane

Later in the season, the team explores the legacy of Sid’s One Stop Shop in North Lafayette goes back to Pointe-aux-Chênes to talk to shrimpers about the ongoing crisis in the industry, visits the Giant Omelette and French Food Festivals in Abbeville and Larose respectively, conducts an exclusive first interview with the new French Consul in Louisiana Rodolphe Sambou, and paints a portrait of the star of “Swamp People” Troy Landry.

Will McGrew, CEO and Co-Founder of Télé-Louisiane, said La Veillée is necessary as part of the broader effort to keep Louisiana French alive. “Each episode constitutes a new, engaging audiovisual resource for French speakers and learners across Louisiana,” he said. “But La Veillée is about more than just French—the show also tells the unique stories of the people of Louisiana and helps remind us to have pride in our unparalleled culture. We are so grateful to be partnering with LPB in this endeavor for a second season.”

All episodes of La Veillée are available online at Télé-Louisiane and LPB.

The Legend of Pachafa

In Avoyelles Parish, a Louisiana Folktale that transcends time and language

In Avoyelles Parish, a Louisiana Folktale that transcends time and language

No historical images of the Pachafa exist, so this artist rendering provides an idea what the mythical creature looked like. Illustration by Burt Durand

By Natalie Roblin

This article was published in partnership with Country Roads Magazine. Read the article and more here.

Mention the word “Pachafa” in Avoyelles Parish and you’re likely to get at least half of a story. For generations, children have feared the tale of the grisly half-man creature coming to steal them away. As for the other half of the tale…well, it depends who you ask.

“When you were a little boy, there you were alone in the woods, in the cypress swamp,” begins anthropologist and Avoyelles Parish native, Dustin Fuqua. “It’s very quiet. You hear a whistle.” He emits a high-pitch whistle through his teeth, then pauses, “and you look up high, high in the tree. Behold! Pachafa!”

Fuqua recounts the tale in Avoyelles-accented Louisiana French, the way he heard it from family members growing up. “Pachafa starts to come down from the cypress tree,” he continues, looking up. “He sees the little boy. In one hand, he offers herbs; in the other hand, he offers a knife. If the little boy chooses the herbs, he becomes a medicine man. If he chooses the knife, he’ll become a warrior.”

While the story of Pachafa is familiar to residents across the parish, it has a prominent presence in the Spring Bayou, otherwise known as Bayou Blanc, community, which is located a few miles outside the parish seat of Marksville, near the Tunica-Biloxi Tribe of Louisiana reservation. For Fuqua, Spring Bayou is the frightening mise-en-scéne for Pachafa. “The earliest recollection I have of Pachafa was riding in the car in the Spring Bayou Wildlife Management Area,” says Fuqua, who was always told by his mother that Pachafa lived in an old Wildlife and Fisheries maintenance building, near the Boggy Bayou boat launch—only about twenty minutes from his family’s home. Fuqua and his family would make the drive often; fear and anticipation building as they crept down the gravel road, closer and closer to Pachafa’s house.

Spring Bayou Wildlife Management Area spans 12,000 acres across the Red River backwater system. A series of coulees, lakes, and rivers flow through the area and its communities, and with them flows the tale of Pachafa. On the edge of the system, running through the middle of the Tunica-Biloxi reservation, is a canal called the Coulée de Greus, which flows into Old River and then into Spring Bayou. In the story of Pachafa, the Coulée de Greus and Spring Bayou, as well as the Fort DeRussy cemetery in the Brouiliette community, are prominent sites in the Tunica and French Creole tellings. As Fuqua points out, Coulée de Greus is a sacred place where cemeteries were once located and, according to some Tunica tellings of the story, where Pachafa camps out. While Pachafa has no explicit homebase, he hovers near and around these historic waterways and the indigenous mounds surrounding them, never shifting too far geographically. ”His story is pretty localized,” says Fuqua, “and, in my opinion, it’s because of the presence of the mounds.”

Language and Transmission

Language bears on the malleable nature of Pachafa’s story and name. The many iterations of the tale exemplify the complex interaction of culture and language that historically make up Avoyelles Parish. While the most widely recognized name for the legend is “Pachafa,” there are various spellings and interpretations. To children who heard the tale from French or Creole speakers, he became “Johnny Pachafa.” Some, like Fuqua, believe this to be an anglicized version of the French folktale “Jean á patte de fer,” meaning “John with an iron paw,” and referring to a character who has a prosthetic foot. For members of the Tunica-Biloxi Tribe of Louisiana, he was “Tanapachafa,” or simply, “Tanap"—which is originally a Choctaw word associated with war.

Dr. Pete Gregory, who is the curator of the Williamson Museum at Northwestern State University, and Donna Pierite of the Tunica-Biloxi Cultural and Educational Resource Center, translated the Tunica legend to “Tanap apah achafa,” loosely describing a half-man, half-warrior with only one leg. According to Fuqua, Gregory, and Pierite’s research, the word “tanap” might also derive from the Tunica word “tana,” meaning “louse,”—a common slang term for a scoundrel or rascal. The Tunica word, “pachafa” is used to describe someone who walks with a limp—a notorious idiosyncrasy of Pachafa.

Though in almost every iteration of the folklore Pachafa is half-man, besides the other half being a warrior—he might instead be half alligator, or half horse. Occasionally, he is simply described as half of a man—limping along railroad tracks or lurking in nearby woods and fields.

Fuqua and Pierite believe that Pachafa’s story may have been adopted from the Choctaw tale of the “Little People”. Similarly, in this legend, a little boy wanders into the woods and is presented with the choice of a knife or herbs. The Tunica-Biloxi Tribe includes many people of Choctaw descent who, over generations, might have reinterpreted this tale and since preserved the story of “Tanapachafa.” Some Tunica versions reference the herbs and the knife, while other versions pit Tanap against the young boy in a wrestling match.

A Rite of Passage

Members of the Tunica-Biloxi tribe consider hearing the tale of the Tanapachafa as a rite of passage. Pierite, who serves as the Tunica-Biloxi Legends and Songs Keeper, has complex feelings toward Tanap. “There was fear, but there was also respect,” explained Pierite. She recalls the ceremonial way in which her grandmother shared folktales—locking the front door, and then her bedroom door, sitting the children on the side of the bed and, in a low voice, passing the knowledge of Tanap to the next generation.

For Pierite, hearing these folktales was a private and personal event. Growing up, she was told not to tell anyone the stories she heard because people would laugh. Keeping them close to your heart was a way to protect yourself from potential judgment or mocking. Pierite describes the difficulty of initially sharing the folktales with the public at Tunica-Biloxi Pow Wows. Over the years, however, her pride vanquished any fears. “This is our inheritance. This is the treasure,” she said.

The intimate nature of native folktales, coupled with the departure of large numbers of Tunica from the Avoyelles area over the past fifty years, may contribute to the strong association of Pachafa with the lore of the French Creole community in Avoyelles. However, like most of the best Louisiana traditions, the story is an amalgam of the many cultures that make up the area. Each of its diverse retellings is pivotal to its preservation.

An Oral Folktale

In the near decade he’s spent researching the legend of Pachafa, Fuqua has not come across any historical references or written accounts of the legendary spirit, other than a brief description he helped to create for the Pachafa Pale Ale brewed at Broken Wheel Brewery in Marksville. The story is ever-changing, ever-evolving, preserved only within the archive of individual memory. This is perhaps what makes such oral traditions so sentimental; we cling to our subtle variations of the stories as a way to remain close to our identities and our ancestors. It is also what makes the folklore a unifying agent, allowing us to bond over commonalities and shared experiences. As Nathan Rabalais explains in his book Folklore Figures of French and Creole Louisiana, “The paradox of specificity and universality is what gives readers and listeners around the world the peculiar impression of both familiarity and novelty.”

Pachafa is regional and specific; always lurking in proximal locations such as cornfields, bayous, or under nearby bridges. According to Rabalais, this process of substituting decorative or surface-level elements of a story—such as what the other half of the half-man might actually be—is called “localization.” “Localization,” explains Rabalais, “is responsible for the relatability of the tale and an affective proximity to its listener.” The stories change and take on contemporary aspects in order to become most relevant to each community, each family, each person.

Conclusion

To unravel the various versions of Pachafa story is virtually impossible, as each tale is so intertwined with the others—all of them, over time, lending themselves to each other. Today, the area’s French Creoles recall hearing the tale of Johnny Pachafa as a 'tit garçon—or little boy—on weekend rides to the camp with brothers and uncles or fathers and grandfathers, not necessarily realizing this story was itself an adaptation of the Tunica-Biloxi’s folktales of the Tanap.

As to how Pachafa, in every iteration, came to be a half man is unclear. This piece of the story seems to consistently change with each telling, but it is always gruesomely creative—a chainsaw, a train, a woodchipper, the devil. The tales of Pachafa do not exist in straight lines running parallel to each other, but rather, as twists and curves, weaving in and out like bodies of water, sometimes flowing in harmony. And sometimes cutting each other off.

Residents of Pierre Part Keep French Alive

Thanks to an effort by elders and children enrolled in an immersion program, this small town has one of the highest percentages of French speakers in the nation.

Thanks to an effort by elders and children enrolled in an immersion program, this small town has one of the highest percentages of French speakers in the nation.

By Sara Guillot

“I love you grand comme ça,” my grandfather would say to me, his arms outstretched as far as he could reach. I was young, before school age, and the words were foreign to me. My grandfather, who is not from here, did not grow up speaking French. However, in Pierre Part, where we’re from, it is nearly impossible to live your life without learning some of the colloquialisms.

Pierre Part is a small town located in Assumption Parish, first settled by Acadians in the late 17th century. Today, nearly 40 percent of its residents still speak at least some French, according to the United States Census Bureau, which is one of the highest percentages of any town in the country. Although the number of native French speakers has declined over the years, the language and culture hold a special place in the hearts of the community.

I started to finally learn the town’s heritage language years later through the French immersion program at Pierre Part Elementary. Only then was I finally able to understand what my grandfather was telling me.

Eventually, I saw French more like a newfound superpower. I could listen to the adults gossiping around town, able to understand what they were saying without giving myself away. When my little sister started to learn French, as well, we treated the language like a secret code that was foreign to our anglophone parents. It wasn’t until much later that I was able to appreciate just what learning French meant to me and my community.

Ray Crochet grew up speaking Louisiana French in Pierre Part. Ethan Castille/Télé-Louisiane

French in Pierre Part began a slow decline when children started to attend public schools in the mid-20th century after the Louisiana Constitution of 1921 declared that the language of instruction in the State’s public schools must be English despite the French-speaking majorities in many communities. Ray Crochet, who grew up in Pierre Part, told me that although his teachers discouraged children from speaking French in class, they were considerate of how difficult it was for them at first.

“They were understanding,” he said. “They could not teach well unless they understood. We were just as foreign to them as they were to us, and they could tell when you were trying your best.” He explained how he got excited to answer a question in class, only for the words to come out half in English and the other in French.

As he grew up, Crochet endured the stigma that outsiders associated with his native tongue. There was a language barrier that kept him and others from Pierre Part socially separated from the rest of the parish, which by that point had embraced English on a larger scale.

“Since you couldn’t express yourself in English as well as the next person, it was registered in some people’s minds as having a lack of intelligence,” he said, referring to working alongside anglophones. “Only intelligence is not measured by what language you speak, or even how fluent your language is.”

Crochet admits to still reverting back to French frequently when speaking with his wife, Bessie, or when meeting up with his old friends. He mentioned how much more naturally French came to them, and how they were more comfortable speaking it than English.

Despite the decades-long downward trajectory of francophones in Louisiana, many Pierre Part residents insisted on passing down the language. Carol Ann Aucoin, former principal of Pierre Part Primary School, gifted the language to her daughters because their grandparents and great-grandparents spoke French.

“My girls spoke French not because they learned it in school, but because we thought it was only fair that they had the ability to communicate with them,” she said.

In 1990, Aucoin was approached by then-superintendent of schools, Ed Cancienne, to discuss improvements to the education system in Pierre Part. Aucoin expressed her desire to start a French immersion program. Cancienne gave her a green light, and she garnered overwhelming support from residents, as well as some of the teachers in the school.

French signs in Pierre Part, Louisiana, where around 40 percent of the population speaks French. Ethan Castille/Télé-Louisiane

In 1991, the French immersion program in Pierre Part officially started with two grades, kindergarten and first grade, making it one of the longest-running programs in the state.

“We thought it best to start with those two classes, and then add another grade each year that passed, all the way through eighth grade,” said Ruth Blanchard, former French teacher at Pierre Part Primary and Assumption High School. “That way, the children were first exposed to the language at a time when they could learn French alongside their home language, and then build upon that foundation as they progressed through school.”

Every day, Blanchard taught half an hour of French to students ranging from kindergarten to fourth grade who were not enrolled in the immersion program. This allowed all of the students to have some exposure to French, even if they were not part of the program.

It was important to the teachers and faculty that they get the community involved. Students participated in various events around the town, such as singing for the Christmas tree lighting, and serving at the French mass at St. Joseph the Worker Catholic Church.

“It meant so much to the community to see these young people speaking French,” Blanchard said. “So many of the older people showed up to mass because they were the ones who could remember having it in French. They never thought they would get the chance to hear it again.”

Students were also involved with the Fais-Do-Do, a Cajun food and music event hosted by Les Amis du Français de Pierre Part, a nonprofit organization that aims to protect the immersion program, in order to showcase the town’s heritage for the younger generations.

Christopher Templet was a student in the French Immersion program from 2006 to 2015 partly because his family members, especially on his father’s side, speak French. At the end of the program, he felt that he was truly bilingual. Now, he will speak French with his family, and he has made francophone friends at school.

“French is something I am going to keep with me forever,” he said. “It allowed me to really feel in touch with the roots of where I’m from. I have a better understanding of life in Pierre Part, of live in general, knowing that this is what my ancestors did. It truly helped me build my identity.”

While some of the immersion students ended their journey after completing the program, there are some who have fully embraced the language, and made it a part of their daily lives, such as Erin Barbier, who was a part of the first class in 1991. Although French faded from her life for a number of years during high school, she was drawn back to it in her senior year. After graduation, she continued to study French in college.

Now she is the world languages instructional coordinator with the Austin Texas Independent School District, and she serves as the immediate past president of the Texas Foreign Language Association. She has opened two French programs in Texas, both of which are still active. Her current position in administration allows her to play a bigger part in helping students who are seeking to learn a second language.

“Pierre Part is a very small town, but the French Immersion program opened my eyes to the history of what it meant to be Cajun, what it meant to come from a family of French speakers,” Barbier said.

Saint Luc French Immersion Campus terminates project, but local pride remains strong

The board of the non-profit purchased a 1960s-era hospital in Arnaudville in 2019, but after funding and renovation issues will sell the building.

The board of the non-profit purchased a 1960s-era hospital in Arnaudville in 2019, but after funding and renovation issues will sell the building.

Mavis Arnaud Frugé at the campus of Saint Luc in Arnaudville, Louisiana. Will McGrew/Télé-Louisiane

By Jonathan Olivier

The board of the Saint Luc French Immersion Campus and Cultural Center, located in Arnaudville, announced on Sept. 17 the project will be terminated and the building will be sold.

Saint Luc, a non-profit organization, purchased the St. Luke General Hospital building in November 2019 in the hopes of renovating it to host French immersion courses. After obtaining the building, which was built in 1967 and sat vacant since 1990, officials with Saint Luc raised money and replaced the aged roof, and began cleaning the inside of the building. Over the years, Mavis Arnaud Frugé, the project’s founder, enlisted the help of volunteers to host workshops and classes.

Despite this progress, it became increasingly clear that large capital costs to bring the building up to standard would be insurmountable for the small community organization. The board will now have the building appraised, and after the sale it will refund investors.

Frugé, the former board president of Saint Luc, worked tirelessly to bring the project to life in her small hometown. Her idea to create the Saint Luc program started as a five-day French immersion session in 2005, which was hosted at the NUNU Art and Culture Collective in Arnaudville by former Louisiana French professor at Louisiana State University Amanda LaFleur. Along with LaFleur, Frugé helped coordinate immersive outings with local francophones, activities that included catching crawfish or kayaking. The program came to be known as “Sur Les Deux Bayous,” paying homage to Arnaudville as the confluence of bayous Teche and Fuselier.

The Saint Luc board purchased the vacant St. Luke General Hospital building in November 2019. Jonathan Olivier/Télé-Louisiane

Eventually, other universities caught wind of the project and were interested—Frugé and NUNU volunteers began hosting immersion sessions for students from across the country.

“I met some wonderful people over the years with this project,” Frugé said. “With our pilot program, we brought many students and schools to Arnaudville that came to learn French and learn about our culture.”

In 2008, Frugé and NUNU founder George Marks hatched a plan to purchase the vacant St. Luke General Hospital building and turn it into a first-of-its-kind French immersion program, building upon what they had already established, and looking to the structure at Université Sainte-Anne in Nova Scotia, Canada, for inspiration.

LaFleur, who most recently served as the Saint Luc board president, said the project was never about a building, but rather a community with Frugé at its core.

“Those who have participated in the activities organized by Mavis and her army of volunteers—French tables, immersion programs, workshops, language and craft classes, cultural gatherings, card nights and poetry evenings—form a community dedicated to this cause,” she said. “Mavis, with her enthusiasm and generosity, invited us all to see the jewel that is French Louisiana from a new perspective. And it's clear from the large number of people who return to Arnaudville again and again that this project is a success.”

Pointe-au-Chien Indian Tribe buys community’s former elementary school

After a lawsuit with the Terrebonne Parish School Board, the Tribe purchased the former Pointe-aux-Chênes Elementary building to serve as a home for École Pointe-au-Chien.

After a lawsuit with the Terrebonne Parish School Board, the Tribe purchased the former Pointe-aux-Chênes Elementary building to serve as a home for École Pointe-au-Chien.

Pointe-aux-Chênes Elementary School was closed in 2021, but will be renovated and house École Pointe-au-Chien. Drake LeBlanc/Télé-Louisiane

By Jonathan Olivier

On Friday, the Pointe-au-Chien Indian Tribe purchased from the Terrebonne Parish School Board the building that once housed the now shuttered Pointe-aux-Chênes Elementary, according to tribal officials. Officials with the tribe plan to allow the building to be used as the eventual home for École Pointe-au-Chien, a new French immersion school that opened in August.

Patty Ferguson Bohnee, a tribal member and attorney for the Pointe-au-Chien Indian Tribe, noted that the one-dollar sale of the building is believed to be part of a settlement of a two-year federal legal battle between the School Board and parents of the former elementary school. Officials with the Terrebonne Parish School Board voted to close Pointe-aux-Chênes Elementary–with one of the highest Indigenous student populations in the state–in April 2021, despite pleas from the community and state officials like Lt. Gov. Billy Nungesser and Speaker Pro Tempore Tanner Magee to allow the school to remain open as a revamped French immersion program.

A lawsuit initiated by 12 parents from the tribe in June 2021 alleged that, by closing the school and refusing, the school board had violated the Civil Rights Act, as well as the 14th Amendment of the Constitution and Article 1 of the Louisiana Constitution, by discriminating on the basis of language and thus national origin against American Indian and Cajun students in the community. In addition, the parents alleged, the school board had failed to adhere to the requirements of Louisiana’s Immersion School Choice Act.

After a year of public outcry from members of the Pointe-au-Chien Indian Tribe, as well as numerous activists and French-language stakeholders, the Louisiana Legislature voted unanimously in spring 2022 to fund and open École Pointe-au-Chien as a public state special school similar to the New Orleans Center for the Creative Arts (NOCCA). The school has an independent board, separate from Terrebonne Parish School Board, whose members were appointed by the Native Tribes of the bayou region of Southeastern Louisiana as well state officials, including the Gov. John Bel Edwards. It now serves as the first French immersion program in Terrebonne Parish.

"It is historic news that our Tribe now owns the school building where so many of our Tribal members and ancestors were prohibited from enrolling and later punished for speaking our heritage Indian French language,” Ferguson Bonhee said. “We look forward to making the building available as a final home for École Pointe-au-Chien upon its reconstruction and know it will continue to be a pillar for keeping the French language and culture of our Indian and Cajun community alive for generations."

École Pointe-au-Chien is temporarily housed at the Vision Christian Center in Bourg, offering grades kindergarten and first. School officials said the program will eventually move to the Knights of Columbus building down the road in Pointe-aux-Chênes while the former school is renovated. Each year, officials plan to add a grade, eventually offering up to the 5th grade. Renovations on the Pointe-aux-Chênes Elementary buildings are expected to take two years, after which point the property will become the homebase for École Pointe-au-Chien

“This is truly a historic day in the fight for Louisiana’s endangered coast, culture, and French language,” said Will McGrew, École Pointe-au-Chien Board President and Télé-Louisiane CEO. “So many people said it would be impossible to open a Bayou French immersion school in PAC. Now we know that not only will we have the school the community has fought for, it will also be housed on Tribal land.”

McGrew added, “In addition to the Tribe's leadership, this victory could not have happened without Jimmy Domengeaux, the parents’ determined pro bono lawyer and the nephew of CODOFIL founder James Domengeaux.”

Leaders reflect on Nathalie Beras’ impact on Louisiana in wake of her departure

Beras, the former consul general of France in Louisiana, stepped down from her role in early August. Local leaders expressed that her impact will be felt for years.

Beras, the former consul general of France in Louisiana, stepped down from her role in early August. Local leaders expressed that her impact will be felt for years.

Nathalie Beras in the coastal wetlands of Louisiana with Albert Naquin, traditional chief of the Jean Charles Choctaw Nation. Courtesy image by Audoin de Vergnette

By Jonathan Olivier

It was September 2021 and Nathalie Beras, the new consul general of France in Louisiana, had just arrived in the state to start her term in New Orleans. Then, Hurricane Ida struck, causing power outages across the Crescent City.

Beras and her staff decided to spend the next two weeks in Lafayette where they worked with local officials to get to know the Acadiana region. Dave Domingue, director of international trade and development at the Lafayette International Center, worked with Beras in that period and noted that her impact on the region’s francophone community was immediately clear.

In one of the first meetings Beras held with Domingue and other francophone leaders of Lafayette, she recommended that the University of Louisiana at Lafayette join the Agence Universitaire de la Francophonie (AUF). “No one at the meeting had ever heard of that,” Domingue said. “So, the university jumped on the opportunity.”

At the end of 2022, the AUF officially approved UL’s membership, which is the first American university to be a member of the Montreal-based network of global universities with francophone concentrations. By the time Beras had gone with her staff back to New Orleans, Domingue said she had left an indelible mark. She had visited smaller francophone communities around Lafayette, like Arnaudville, and showed a genuine interest in understanding the region’s unique challenges and assets—something not all past consuls have done extensively.

“She's given the francophone community here a lot of validation and a lot of recognition,” Domingue said.

Beras stepped down as consul general in early August, leaving behind a legacy that has been characterized by state and francophone leaders as sincere efforts to venture outside of New Orleans and interact with the bulk of Louisiana’s francophone community, which is often found in smaller towns or throughout the countryside of south central and southwest part of the state. From early on, Beras was impacted by the welcome she received in these communities, as well as the widespread attachment to the French language.

"I met the warmest people in these communities that immediately welcomed me into their midst,” Beras said. “I was able to measure the extent to which the French-speaking world is at the very heart of this region, and is enjoying a wonderful renaissance here that is inspired by music and its oral traditions.”

In particular, Beras was supportive of the efforts by south Louisiana’s Indigenous people who often comprise the largest concentrations of French speakers in the state.

“Nathalie has been very supportive of the Tribe,” said Patty Ferguson, a tribal member and attorney for the Pointe-au-Chien Indian Tribe. “She has basically made the effort to go into the communities and be part of these communities, while recognizing the dialects of the other French speakers in Louisiana.”

Beras at a meeting for the opening of École Pointe-au-Chien in 2023. Photo courtesy of Audoin de Vergnette

Beras worked with the Pointe-au-Chien Indian Tribe to highlight their needs as they rebuilt from Hurricane Ida, as well as during their fight to establish the first Indigenous French immersion school in the state, which opened in August, called École Pointe-au-Chien.

“She didn’t just come and do a tour,” Ferguson said. “She has been very active with the community and has invited us to different events. She made sure our leaders were on the list when President Macron came out to New Orleans. Our chairman was able to shake the hand of the French president—that’s pretty huge.”

Among Beras’ other notable contributions to increasing Louisiana’s visibility in la Francophonie was the December 2022 visit from President Emmanuel Macron, which was the first visit from a French President to Louisiana in almost 50 years. In the leadup to the tour, she played a critical role in convincing the president and his team to visit Louisiana, as well as coordinating all aspects of Macron’s visit.

Bears also assisted Gov. John Bel Edwards as he twice visited France, and she negotiated the creation of a delegation of Louisianans that included Edwards to attend the“Fête de la Musique” at the Elysée Presidential Palace in June. Edwards’ visit was the first in 40 years by a Louisiana governor, with francophone Gov. Edwin Edwards being the last to visit the Élysée in 1984.

“I want to thank Consul General Nathalie Beras for her historic work supporting the French language in Louisiana while developing unprecedented economic and cultural partnerships between Louisiana and France,” Edwards said. “I was particularly proud to work with her to welcome President Macron to Louisiana—a first in almost 50 years—and to create a position for a French energy and environmental advisor within my administration. We are sad to see her go, but I am confident her impact will continue for years to come.”

In New Orleans and the surrounding coastal region, Beras was able to see first-hand the impacts of climate change and land loss. She therefore made it a priority to assist Louisiana’s francophone communities who are often at the front lines of these climate issues. Specifically, she facilitated the signature of a first-in-its-kind agreement between the governor and French Foreign Minister Catherine Colonna to fund the creation of a French energy and environmental expert role within the Louisiana government.

Beras coordinated many aspects of President Emmanuel Macron’s visit to Louisiana in December 2022. Photo courtesy of Audoin de Vergnette

The expert, Emmanuel Henriet, arrived in Louisiana in early August just before Beras’ departure, and he will be housed within the state’s Coastal Protection and Restoration Agency (CPRA), also working with Louisiana Economic Development (LED). Louisiana’s closer relationship with France in this domain could lead the state to adopt a bolder energy and climate strategy that opens up economic opportunities for Louisianans.

Beras also worked closely with immersion programs, especially those certified by the Agency for French Teaching Abroad. Tiguida Mathieu, Chief Academic Officer of Lycée Français de la Nouvelle-Orléans, the first such public French program in the United States, noted that Beras was an instrumental partner to further developing the school’s mission.

"The Lycée Français has benefited from the Consul General's deep commitment to education and her commitment to equality and equity,” Mathieu said. “She took a great interest in the Lycée Français because it's a school that embraces diversity. In other words, it's a diverse school where all the children of Louisiana—Black, white, Hispanic, from all walks of life—come together. And that's something Nathalie Beras has supported and developed a great deal.

Beras noted that the key to progress in Louisiana is the growth of French speakers, a unique asset in the state. "Louisiana's youth is energetic and combative, and the determination of these young people in universities and immersion schools is remarkable,” she said.

“I have only one word to say to everyone in my farewell: lâche pas!”

École Pointe-au-Chien opens as first French immersion school in Terrebonne Parish

On August 16, school leaders and teachers welcomed students in kindergarten and first grade.

On August 16, school leaders and teachers welcomed students in kindergarten and first grade.

Gaëtan Lombard introduces basic French words to the inaugural class at École Pointe-au-Chien on August 16, 2023. Jonathan Olivier/Télé-Louisiane

By Jonathan Olivier

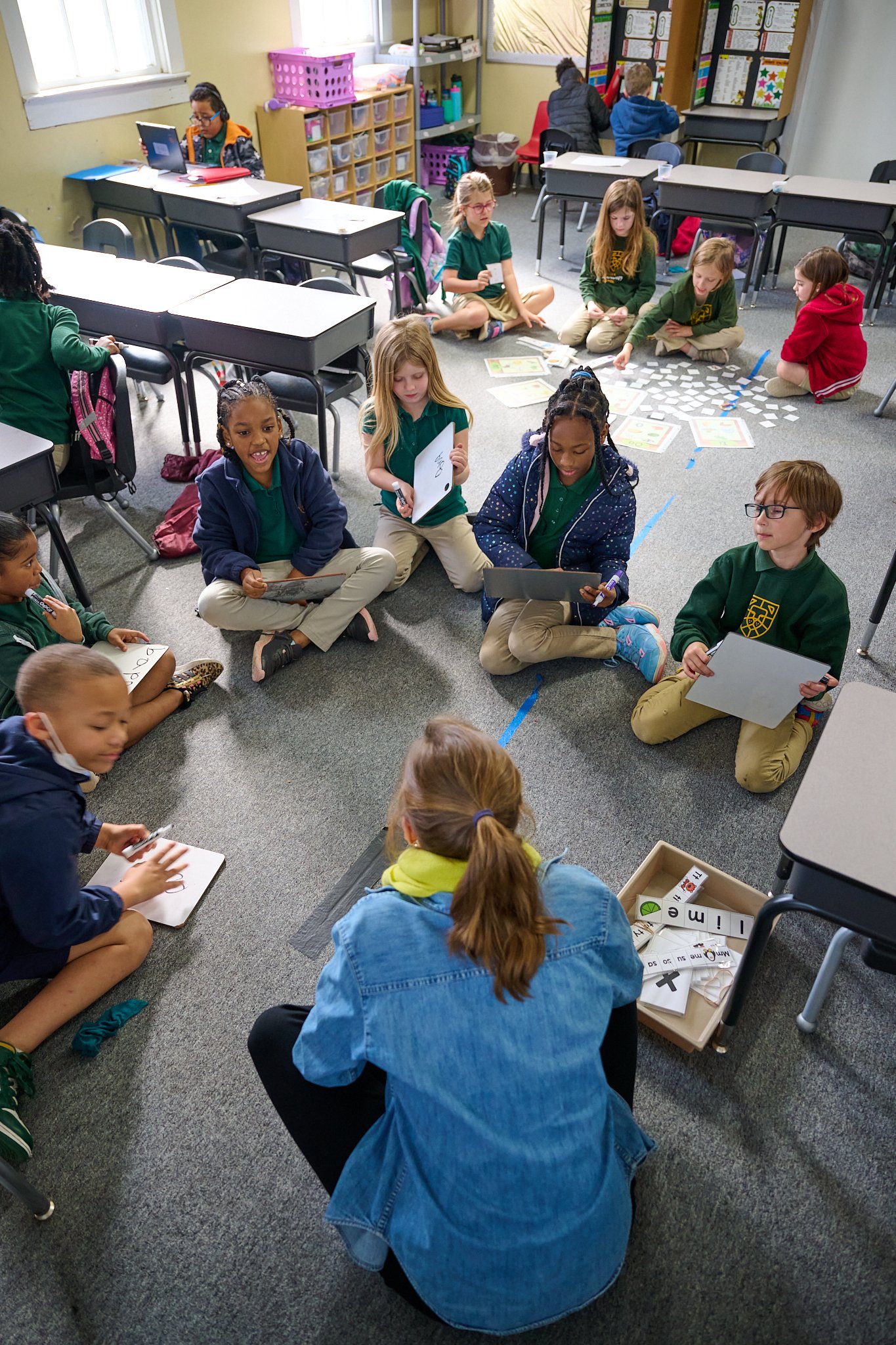

Gaëtan Lombard sat in a low chair in front of his three students, his hand in a panda puppet, leading an ice-breaking activity to coax them into uttering their first word of the day in French.

Bonjour, Lombard repeated over again, until, one by one, his students began repeating the word themselves. These three children, who on August 16 participated in the first day of school of the inaugural academic year of École Pointe-au-Chien, continued their day immersed in French by learning days, months, numbers and simple commands.

School officials welcomed kindergarten and first grade at the Vision Christian Center in Bourg where the school will be housed for a few months until moving to the Knights of Columbus building just a few miles down the road in Pointe-aux-Chênes. After a year or two of renovations at the site of the former Pointe-aux-Chênes Elementary that closed in 2021, the school will move there as its permanent location.

École Pointe-au-Chien, authorized and funded by the state legislature, opened as the first French immersion school serving a predominant Native American population. Christine Verdin, the school’s executive director and a native French speaker from the Pointe-au-Chien Indian Tribe, said her school will be the first to incorporate, on a large scale, the local Louisiana dialects spoken by the Indigenous and Cajun communities nearby. French is still used daily up and down the bayou in these parishes, Verdin said, by grandparents and other family members.

École Pointe-au-Chien opened as the first French immersion school serving a predominant Native American population. Jonathan Olivier/Télé-Louisiane

“Even though Gaëten is French, he has already started adding Louisiana French words into his lessons, because he understands that it’s important for us and our children to learn our French, too,” she said. “We’re including Louisiana French, spoken by Cajuns and Indians, and the culture of the two.”

Cynthia Breaux Seitz, a francophone from south Lafourche Parish, is teaching English language arts and will be supported by Cynthia Owens, a French-speaker from Thibodaux, who is also teaching social living and art.

This focus on local teachers and the continuation of the regional French dialect lie at the core of the school’s mission to both preserve and continue the culture of the many bayou communities that make up Terrebonne and Lafourche parishes. Will McGrew, CEO of Télé-Louisiane and president of the École Pointe-au-Chien State Board, said this aspect sets the school apart from the more than 30 immersion programs in the rest of Louisiana.

“If you look at other minority language situations, the whole point of the schools in the minority language was to keep the language and culture alive as it's spoken there, as opposed to just being a second language,” he said. “Whereas, sometimes when immersion schools in Louisiana are pitched, it's kind of blurred nowadays, where it's like, is it just to learn a second language or is it specifically to keep Louisiana language and culture alive? And with École Pointe-au-Chien, you can really see that, of course you are learning a second language, but the primary impetus for the school is to keep the local language and culture alive.”

In order to introduce students to the region’s French, Verdin said they’ll have francophone members of the community visit for cultural workshops, discussing topics like shrimping and local Indigenous practices like palmetto basket weaving. This focus on continuing not only the region’s language but the culture that it’s tied to is among the reasons École Pointe-au-Chien garnered so much support from state officials. Gov. John Bel Edwards has repeatedly expressed this important point as he has provided support for funding the school.

École Pointe-au-Chien will eventually be housed at the site of the old Pointe-aux-Chênes Elementary. Jonathan Olivier/Télé-Louisiane

“The language and culture of our coastal communities like Pointe-aux-Chênes and Isle de Jean Charles are part of what makes Louisiana a state like no other,” Edwards said. “I’m proud to see the work of this community and leaders in the legislature, especially Speaker Pro Tempore Tanner Magee, to pass this heritage on to the next generation with the creation of the first French immersion school in Lafourche and Terrebonne.”

Rep. Tanner Magee, R-Houma, was outspoken in his support for École Pointe-au-Chien, noting that it’s an added value and an asset to the region. “I am thrilled that Louisiana is investing in our communities and culture by bringing this kind of education to Terrebonne,” he said. “Building all the levees in the world will not matter if we do not invest in the people behind them.”

Rep. Beryl Amedée, R-Houma, who attended École Pointe-au-Chien’s opening day, said that a time when native speakers of Louisiana French are often older than 60, École Pointe-au-Chien is an important tool in the fight to save what’s left. Amedée pointed out that by building a new generation of francophones in the region, these communities will be better equipped to continue what’s been passed down.

“We have a future here,” she said. “We can write new songs in French, for example. We can have new traditions and keep up moving forward with modern times, because we don't just want to preserve the past—we want to continue our culture into the future.”

Télé-Louisiane CCO Drake LeBlanc receives 2023 French Culture Film Grant

LeBlanc and producer Rachel Nederveld’s film, “Footwork,” explores Creole trail riding culture in south Louisiana.

LeBlanc and producer Rachel Nederveld’s film, “Footwork,” explores Creole trail riding culture in south Louisiana.

Drake LeBlanc (right) will receive $25,000 as the winner of the 2023 French Culture Film Grant. Drake LeBlanc/Télé-Louisiane

By Jonathan Olivier

This year’s $25,000 French Culture Film Grant from #CreateLouisiana has been awarded to Footwork, a film that explores the Creole trail riding culture of south Louisiana. Drake LeBlanc, the film’s director as well as chief creative officer and co-founder of Télé-Louisiane, and producer Rachel Nederveld, provide an abstract portrait of Creoles in Louisiana, as well as their strong connection to horses.

“I cannot imagine a more deserving filmmaker to receive support from #CreateLouisiana and its partners,” Nederveld said of LeBlanc. “We’re so grateful for their partnership in making this intimate portrait of Drake’s Creole roots and trail riding.”

LeBlanc, who has been working on the project for several months, will continue collecting and compiling footage for the film’s premiere at the 2024 French Film Festival, which will be held in March 2024 in partnership with the New Orleans Film Society.

“I’m excited to have support in making this documentary that will bring Louisiana’s culture to the rest of the world,” LeBlanc said.

The grant aims to support films made in Louisiana that showcase francophone culture in partnership with TV5Monde USA. This year, the grant also has additional support from the Louisiana Economic Development’s Entertainment Development Fund. Other supporters include Cox Communications, Deep South Studios, and the Council for the Development of French in Louisiana.

“TV5MONDE USA has an unshakable commitment to both the community of Louisiana and to showcasing unique stories about the local francophone culture,” said Patrice Courtaban, TV5MONDE USA CEO. “We are thrilled to celebrate the newest #CreateLouisiana French Culture Film Grant winner, Footwork, as they join an illustrious group of filmmakers who have made an impact on not only their community but the greater North American French speaking community.”

As the grant recipient, the film may also be broadcast on TV5MONDE USA, and it will be a part of the “Enseigner Le Français” lesson plan available on the French company’s website, serving as a resource for students around the world.

“#CreateLouisiana is thrilled to offer this unique grant opportunity again this year,” said Scott Niemeyer, #CreateLouisiana founder. “Each year, applicants statewide show us a diverse array of stories depicting Louisiana’s past and present ties to the French language and francophone cultures. We are committed in our efforts to support Louisiana creatives, and the successful continuation of the French Culture Film Grant is a great example of that commitment.”

Colby LeJeune joins KRVS as new host of ‘Bonjour Louisiane’

LeJeune began his role in late July with plans to dedicate air time to French tables, Cajun jams and interviews with Louisiana francophones.

LeJeune began his role in late July with plans to dedicate air time to French tables, Cajun jams and interviews with Louisiana francophones.

Colby LeJeune is live Monday through Friday, from 5 a.m. to 7 a.m., at Cypress Lake Studios on the campus of the University of Louisiana at Lafayette. Cheryl Devall/KRVS

By Jonathan Olivier

Like most people his age, Colby LeJeune didn’t grow up speaking French. Rather, the language was scattered here or there in his English through various words—such as bouder or envie. As is common for many people in the region, the folks in his small community of L’Anse LeJeune in Acadia Parish speak a dialect of English that is strongly influenced by French in terms of inflection, too.

“I was raised with an English that was influenced a lot by French,” said LeJeune, 25. “That helped a lot to already have acquired the sounds of Louisiana French.”

He studied linguistics at Tulane University, but only really started learning Louisiana French in his early 20s. In addition to using books and YouTube videos, LeJeune began venturing to French tables a few years ago. His francophone family members had already passed, so these informal gatherings gave him the opportunity to hear native speakers while practicing his growing vocabulary, too.

“For just about everyone, it’s the only way to learn Louisiana French if you don’t have someone in your family who speaks it or who you can speak with,” he said. “The French tables are specifically for speaking French. The people who come are ready to talk and they want to speak French. It’s all of the ingredients in a single place.”

LeJeune, who is also a master’s student in the French department at the University of Louisiana at Lafayette, stepped into his new role on KRVS' morning program “Bonjour Louisiane” in late July. The show, hosted entirely in French, has a format which has typically been dedicated to broadcasting Cajun and Zydeco music. While LeJeune said he plans to still dedicate much air time to the region’s music, he plans to visit the many French tables around Lafayette in order to document these conversations. He feels that these outings will provide the audience with a way to hear the area’s various accents and the colorful expressions of Louisiana French.

Cheryl Devall/KRVS

In the studio, LeJeune said he also plans to conduct live interviews with musicians and members of the francophone community. He’ll also record jam sessions that take place around Lafayette, such as the Wednesday night Cajun jam at Blue Moon Saloon. LeJeune said he plans to also continue transmitting the sort of cultural information that former host, Ashlee Wilson, featured during her tenure.

“I’d really like to continue what Ashlee had been doing, providing all of the various folklore information, and the stories behind the songs,” he said.

Wilson took over Bonjour Louisiane in September 2022 when Joseph “Pete” Bergeron retired after having hosted the program for 41 years. General manager of KRVS, Cheryl Devall, noted the value of LeJeune’s commitment to continuing this legacy of honoring the area’s culture and heritage languages.

“Around Lafayette I've crossed paths with Colby at Cajun jam sessions, and he's a regular at multiple French tables,” Devall said. “He brings great energy and enthusiasm to his new role with Bonjour Louisiane, and I'm really pleased that he's taken it on.”

For LeJeune, the program will continue to serve as a way to broadcast French to Louisianans who might have few other outlets to hear the language—from older native speakers to younger people wishing to hear what French sounds like in the state.

“If I didn’t have a radio, I wouldn’t have heard French in my everyday life,” he said. “It was thanks to stations like KRVS and KBON. It was a way to hear French every day.”

Bonjour Louisiane is live Monday to Friday, from 5 a.m. to 7 a.m. on 88.7 FM, or online at krvs.org.

Nungesser, Local Officials See Opportunity in Saints France Expansion

Leaders in state and local government view the Saints-France partnership as a potential boon for Louisiana.

Leaders in state and local government view the Saints-France partnership as a potential boon for Louisiana.

Saints staff raised the French flag in front of their headquarters after announcing the France-Saints partnership in May. Wayan Barre/Télé-Louisiane

By Jonathan Olivier

In May, the New Orleans Saints announced a market expansion to France that seeks to grow partnerships between the two francophone regions. While concrete details are yet to be announced on what those connections will look like, local leaders are already planning for Louisiana’s increased visibility in the French-speaking world.

“This is no doubt a new chapter in our bilateral relations to promote Louisiana in France,” said Nathalie Beras, consul general of France in Louisiana. “Not only will this opportunity increase our trade, but we can also hope that it will attract more French investors, projects, tourists and talent here.”

This partnership is a part of the NFL’s Global Markets Program, which launched last year as part of an effort to encourage its U.S. football teams to engage fans around the world. The Saints’ French expansion is the team’s first entry into the program as well as the first time France has been chosen as a target market. Compared with other NFL teams, the Saints expansion is especially practical given the region’s historical ties to France, said Ed Verdin, public relations director for the Franklin city government.

“It not only becomes about introducing an international audience with football but, unlike any other NFL team, this will highlight the culture, people, food and music that has deep roots in France,” Verdin said.

Harahan Mayor Tim Baudier echoed a similar sentiment that this cultural connection differentiates Louisiana from other states and, thanks to the new partnership, it’s something that his town can build on. In particular, Baudier sees the partnership as a catalyst for developing a stronger intergovernmental and economic relationship between France and all of Louisiana. For instance, he said there could be a direct flight between New Orleans and Paris, more university partnerships, funding for more French immersion programs, and even the opportunity for Louisiana to have a more involved role in the Organisation internationale de la Francophonie (OIF).

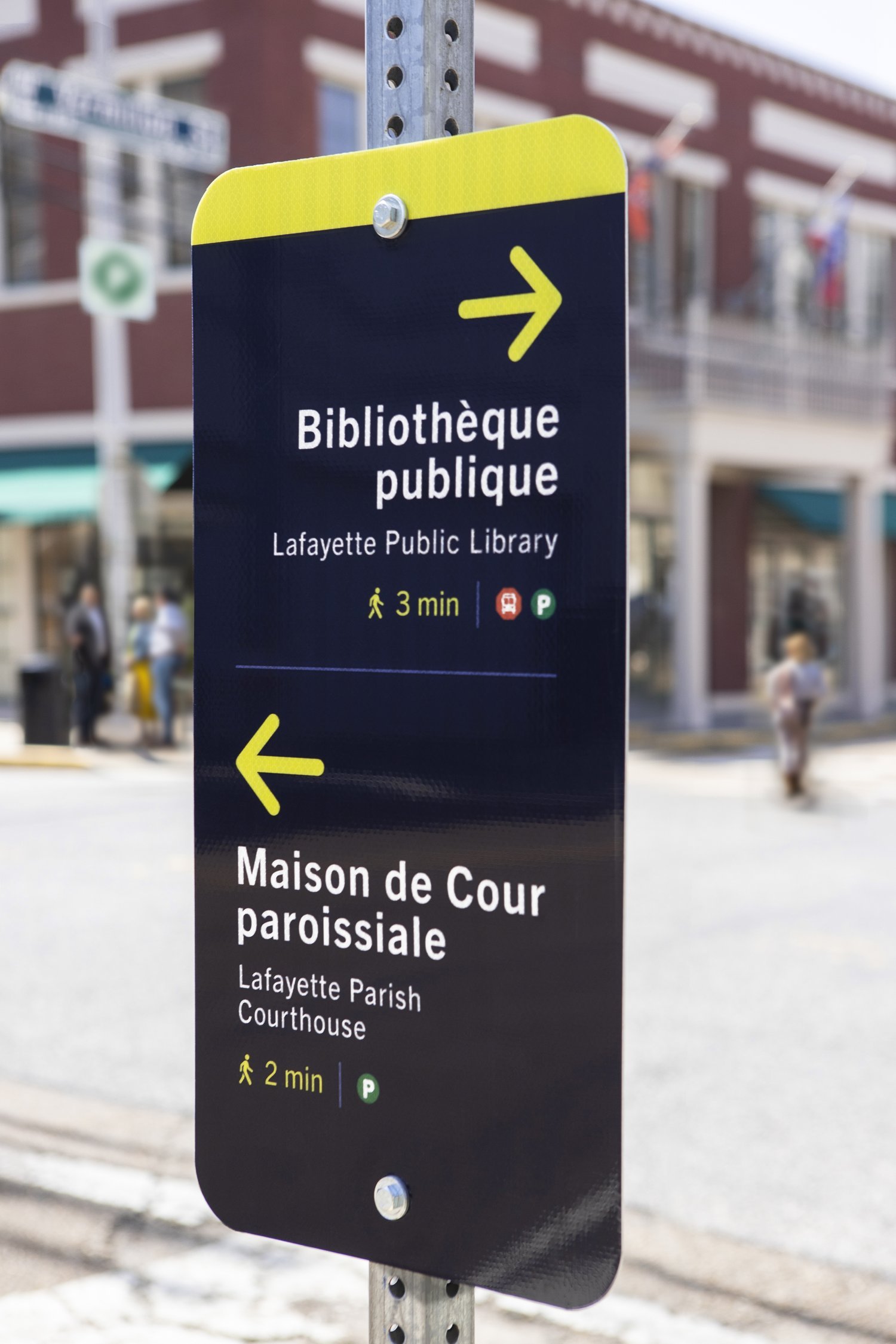

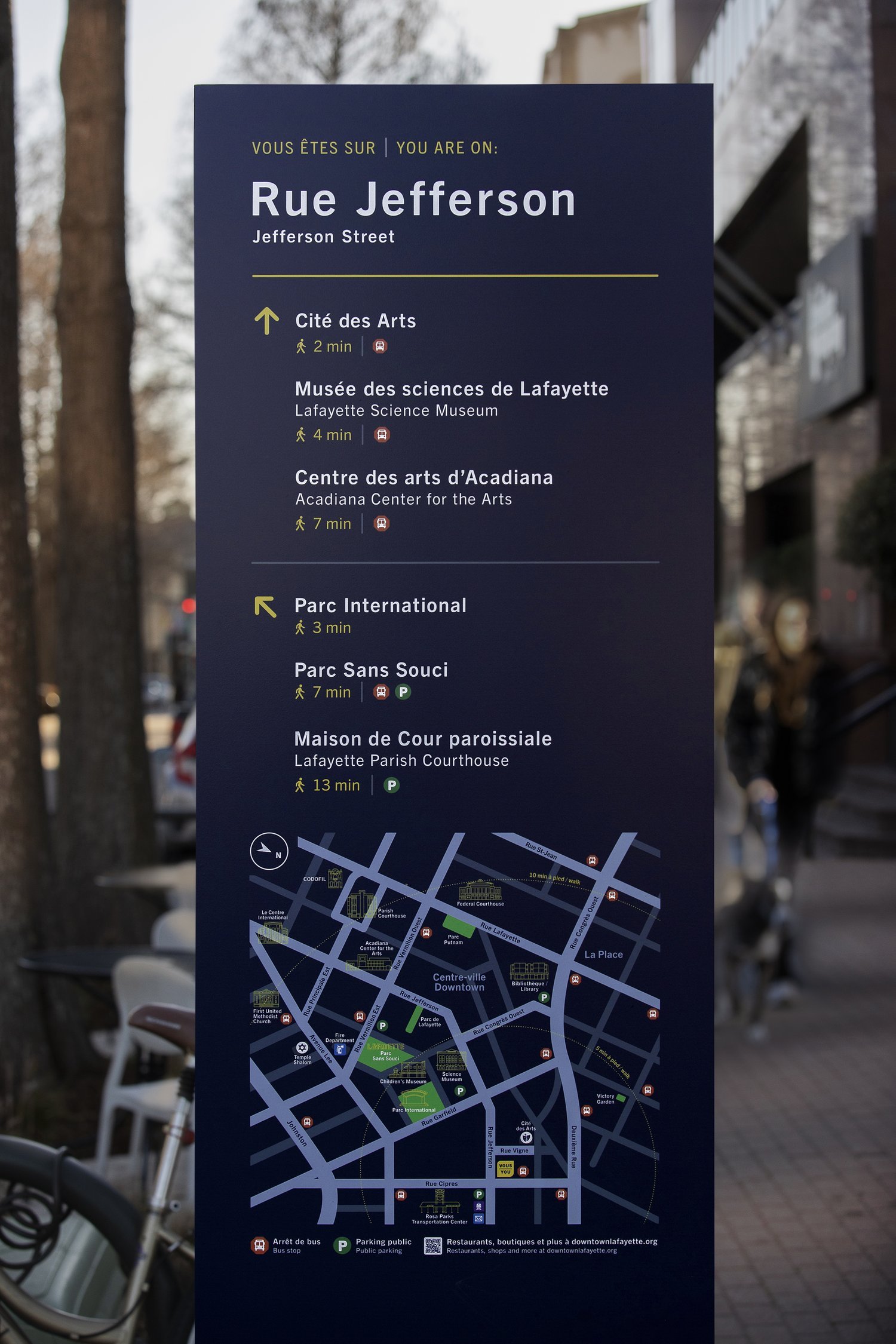

In the meantime, Baudier said that Harahan is beginning its own francophone initiatives. “We are partnering with Alliance Française de La Nouvelle-Orléans to learn the language,” he said. “We’re developing sister city alliances with cities in Quebec and France, incorporating bilingual signage where practical as part of our wayfinding sign program, and exploring a K-12 French immersion program here in town.”

Francophone tourists have long been an important piece of Louisiana’s economy—they make up a large percentage of the visitors to Louisiana each year. Lieutenant Governor Billy Nungesser sees the partnership as a chance to provide another avenue for these tourists to come to Louisiana.

“With Louisiana’s historical connection to France, the granting of the New Orleans Saints international marketing rights in France is another opportunity to bring awareness of what our great state has to offer to an international market,” Nungesser said.

Hitachi

How the rice cooker became a staple of Acadiana food culture.

How the rice cooker became a staple of Acadiana food culture.

The Hitachi rice cooker arrived in Louisiana in the late 1960s. Since then, it has become a staple in Cajun and Creole kitchens. Photo provided by Lucius Fontenot

By Jordan LaHaye Fontenot | Country Roads Magazine

This article was published in partnership with Country Roads Magazine. Read this article and more at countryroadsmagazine.com.

It was the early 1970s, at noon on a Thursday or a Friday. Housewives across Acadiana were preparing lunch, little kitchen TVs turned to Channel 10—Bill Bessun’s typical greeting, “Hi, Bill Bessun here, you’re watching Meet Your Neighbor Acadiana" playing in the background. Looking up from the pot or the oven or the sink, they saw something curious on the television screen: a squat little machine, and a hand scooping rice into it. The camera then zoomed out, focusing again on Bill—who was proceeding as usual. “Hm,” they mumbled, stirring and scrubbing away. The show went on, every now and then panning back to the odd pot of rice, which had started to steam.

Finally, about halfway through the show, Bill looked at the camera and smiled. “Now, if y’all were wondering what we were doing when the show started …”—the camera zoomed back in on the machine—“what we’re doing is making perfect rice. In a Hitachi rice cooker!” At this, someone lifted the lid and reached in with a spoon, pulling out a fluffy, steaming pile of medium grain rice. “You can now get one of these for yourself at Floyd’s Record Shop over in Ville Platte.”

“And the phones never stopped ringing after that,” Floyd Soileau remembers of the most successful advertising campaign of his career. “The ladies were sold on it.”

The Hitachi Rice Cooker's Arrival in America

The mid-century Japanese invention had already risen as a symbol of women’s liberation half a world away—after a Toshiba washing machine salesman discovered that washing clothes was less trouble for Japanese women than the task of preparing three rice-based meals a day. When the salesman proposed the idea of an automatic rice cooker to an engineer, who did not know how to cook rice, the engineer’s wife Fumiko Minami set herself to the task—developing the model still at the base of the appliance almost a century later. During the first year, Toshiba sold 200,000 rice cookers a month. A manufacturer’s race ensued, in which companies across Asia rushed to create their own prototypes. One of those was Hitachi.

By 1958, Hitachi rice cookers had made their way across the Pacific to Hawaii—whose Asian-influenced cuisine also heavily incorporates rice. The trend slowly stretched its way to California—one of the earliest mainland advertisements for the appliance (promoted as being sold at a local Asian market) appearing in the Stockton Evening and Sunday Record in 1966.

“It’s interesting, the idea that the mention of this appliance throughout South Louisiana, would cause people to get really nostalgic and go into these really sentimental stories. People remember that thing very fondly . . . there’s a respect for it—sort of this weird adoration for this artifact.” - Lucius Fontenot

At the time, Americans who encountered the rare machine considered it a foreign novelty more than a revolutionary tool. Hitachi had bigger fish to fry in the American market than a rice cooker—and was devoting more time and advertising money towards their automotive, electronic, and computer products.

But somehow, in the years between 1966 and 1970, the Hitachi rice cooker made its way to Acadiana, where hundreds of miles of fields were freshly a-wave with the products of the still-emerging rice farming industry, and where the regional diet was largely made up of rice dishes like gumbo, jambalaya, étouffée, boudin, and daily plates of rice-and-gravy.

There is more than one origin story attempting to explain the Hitachi rice cooker’s arrival in Acadiana, all difficult to verify with certainty. But newspaper archives show that a Lafayette Asian market called Tomiko’s was placing advertisements for the product in the Daily Advertiser in 1970, selling it as a machine (priced at $26.50) that “Cooks perfect rice every time—automatically—and STAYS HOT AS LONG AS YOU WANT!” At the same time, regular advertisements in the Alexandria Town Talk were promoting them in the classifieds at a price of $19.95, and with a choice of colors.

It was around this time that two Evangeline Parish businessmen, totally independently, encountered the product that, in their hands, would come to revolutionize Cajun and Creole cooking.

Guillory Wholesale

It is difficult to pinpoint exactly when Bruce Guillory and his wife Gladys, owners of Guillory Wholesale in Mamou, first started selling the Hitachi rice cookers. In an article published in 2000 in the Ville Platte Gazette, Gladys cites the date as the mid-1970s. Their son Paul estimated the late 1960s or early 1970s—which is likely more accurate; a Gazette article from November 1971 announces that Guillory Wholesale donated “one of those fabulous Hatachi [sic] 8-cup electric rice cookers” to the Mamou Volunteer Fire Department for their Christmas party raffle.

Regardless, according to Paul, Bruce first encountered the rice cookers at a trade show—likely in Chicago or Dallas. “As I recall, he initially purchased four rice cookers to try—one for my mom, one for his mom, one for Gladys Mayeux, and one for Hazel Deshotels (his two sisters),” he said. “All were pleased with their performance, and he then started selling them like hotcakes.”

“They couldn’t believe the amount of—‘steamers’ they called them—that we were selling. They came here to thank us for that. They had to air freight them into Louisiana. They never expected that. They didn’t know what the hell was going on.” - Floyd Soileau

Arthur Courville, who worked as a delivery man for Guillory Wholesale for fifteen years, remembers the first sale—“We retailed it for $13 a piece,” he said. “And the store made a profit.” It started slow, he recalled. But then “Before you knew something, we were delivering them by the case to the mom-and-pop stores in the country” from Crowley and Basile to Marksville. Once a week, Bruce would go to Lafayette and sell there—“he’s the one that really started pushing the rice cookers in the Lafayette area, too. He really sold a lot, and then it started expanding. I mean, it got to where we were selling … it was unreal what we were selling.”

In the 2000 Gazette article, Gladys explained that the product succeeded because the local people approved of it. The quality was still there, and it was less trouble for the cook.

Floyd’s Record Shop

Around the same time, Ville Platte record producer Floyd Soileau was working directly with Hitachi, selling their stereos, tape recorders, and televisions. (Again, the dates are difficult to verify with certainty, but the earliest Floyd’s Hitachi rice cooker newspaper ad I could find is from 1972.)

Through the grapevine, he learned that Hitachi had another product that might appeal to local cooks. “I had never heard of that before,” he said. He had one of his employees purchase one, and brought it back home to his wife, Jinver. He asked her if she would try to use it to cook the rice for the next day’s lunch.

“So, next day, I’m anxious to get home for lunch, and she’s all disappointed,” he recalled. “She says, ‘Oh, the baby’s crying. I didn’t have time to read the instructions, and I couldn’t do it.” The next day, though, when Soileau came home for lunch, “she had a smile from ear to ear.” She loved it, and described the rice as “perfect”. “That’s all I wanted to know,” said Soileau.

Back at the office, he placed an order from Hitachi for six or seven cases of the rice cookers in various colors and sizes. “We started selling,” he said. “I was trying to get my record dealers to stock it and sell it, but I knew we’d have to do something to let the people know about it.” Thus, the ad spot on Meet Your Neighbor—plus plenty more. Soileau saw the gap between the product and the market—which was basic knowledge of its capabilities—and he spent hundreds of dollars getting the word out. It wouldn’t be an exaggeration to say that the cultural place the Hitachi rice cooker holds in Acadiana today can in large part be attributed to this very advertising campaign. “Nobody had done any promotion,” he said. “The other distributors didn’t want to spend money advertising somebody else’s product. But we were getting orders in-store. We were making money off of this.”

There were other rice cookers, Soileau laughed. “But nobody wanted the Panasonic, because nobody had tried them before. The Hitachi was a proven thing, we approved it. And so, we had the market for it. It was a beautiful set up.”

“The Item to Have in a Cajun Home”

Throughout the 1970s, the Hitachi rice cooker became a coveted newfangled addition to almost every Cajun or Creole kitchen. “Before the rice cooker,” explained Soileau, “Cajun brides had to learn to cook rice in this special little pot on the stove, and you had to use it every day, and get the measurements just right, and cook it just right so you wouldn’t ruin it.” At the 2000 Festival de Musique Acadienne in Lafayette, which was dedicated to Soileau for his contributions to recording and promoting Louisiana French music, Barry Ancelet introduced him as “a young man that probably saved more Cajun marriages than anybody else we can think of”. As it had in Japan, the rice cooker condensed an hours-long process into a few minutes and a single push of a button—granting women more time to spend outside of the kitchen. “The Hitachi rice cooker was the number one gift for newlyweds, at the top of every registry,” said Soileau. “It was the item to have in a Cajun home.”

For a time, the two main distributors of the product in Louisiana were in fact Floyd’s Record Shop and Guillory Wholesale—who were each selling the things by the truckload. The often-repeated oral history claims that the sales reached such monumental heights as to make Louisiana, and Evangeline Parish specifically, the site of the single largest distribution of Hitachi rice cookers outside of Asia. Per local lore, to better understand this phenomenon, executives from Hitachi Corporation in Japan flew to Evangeline Parish to see it for themselves. “They visited Ville Platte and Mamou and all that, thanking us for selling their product,” said Soileau. “They couldn’t believe the amount of—‘steamers’ they called them—that we were selling. They came here to thank us for that. They had to air freight them into Louisiana. They never expected that. They didn’t know what the hell was going on.”

Paul Guillory confirms this, recalling that the executives were actually attending a trade show in New Orleans, and had rented a car to visit Evangeline Parish to figure out why this tiny rural area had such a fierce demand for the cookers. Of course, when they drove the roads leading into Evangeline, the seemingly-infinite fields of rice would have delivered as quick an answer as any. Photographs from Paul’s family archive document the executives’ meeting with his parents, Bruce and Gladys seated with the suited Japanese men at their kitchen table right at the center of a quintessentially 70s-style kitchen, sipping coffee.

The Louisiana market purportedly had its role in the appliance’s evolution, as well. Paul and Soileau each recall that a change to the product was suggested to manufacturers that would make it less reactive to the amount of salt Louisianans tended to add to their rice. “We told them to change that,” said Soileau, “and they did.”

And then there was the matter of size. Originally the cookers came in three-cup, five-cup, and eight-cup options. “We needed a ten-cup,” said Soileau. “And then later they came up with even larger ones for restaurants.”

Eventually, the area's big box stores got wind of the product’s popularity, and Hitachi rice cookers became available everywhere. Guillory Wholesale kept a healthy stock going at the small shops across the region, but Soileau—frustrated that Hitachi was going to stop using him as a main distributor and sell directly to the department stores—quit selling them. “I spent all this money helping you get this program set up, and now you’re going to cut me out? Nah, that was it,” he said.

By that point, though, the Hitachi rice cookers had become a ubiquitous part of the landscape. People could hardly remember cooking rice any other way.

The Enduring Legacy

In 2023, Hitachi still sells rice cookers, but these robot-esque multi-setting $100+ products are rarely found in Acadiana, and hardly resemble their predecessors at all.

Still, the idea of the rice cooker as a kitchen necessity has not dwindled here. When I went off to college, I purchased my own three-cupper and packed it up with my toaster and my microwave. Rice is still a staple in Acadiana’s small towns, and this is how you cook it.

And even I, born at the end of the millennium, know exactly what a 1970s Hitachi rice cooker looks like, and I can place it on my grandmother’s counter—from which we served ourselves so many gumbos and gravies. And like most of the others, still steaming in Cajun and Creole kitchens for miles ‘round, it still works just fine.

“It’s one of those things where, as an adult, it’s like—wait how do I get one of those?” said Mamou-raised, Lafayette-based photographer and filmmaker Lucius Fontenot. “They’re always around.”

Inspired after inheriting his grandmother’s avocado green cooker and photographing it, Fontenot found himself drawn into the enduring legacy of the cooker—discovering how many people he knew still had them and had intense memories associated with them. “It’s interesting, the idea that the mention of this appliance throughout South Louisiana, would cause people to get really nostalgic and go into these really sentimental stories. People remember that thing very fondly . . . there’s a respect for it—sort of this weird adoration for this artifact.”

His ongoing Hitachi Rice Cooker project features photographs of cookers still in operation in kitchens across Acadiana, combined with interviews of their current owners—altogether forming a tapestry of Acadiana’s culinary history centered around this little Japanese invention, which is now as thoroughly Louisianan as corner store boudin, or gravy on rice.

"It was like the dinner bell—‘Come serve yourself a plate!’ —Kirstie Cornell

"My cooker has been with me for more than thirty years—it outlasted my marriage, and has fed me in a way that goes beyond bringing rice to the table. —Sarah Spell

"In the back shed, we found two Hitachi rice makers, still in the boxes. I said, ‘That’s mine!’ I think we kept the other one in the box just in case someone’s breaks or dies. The other brands of rice cookers just don’t work right. They don’t have the ‘ding!’" —Rachel DeCuir

“I mean,” laughed Fontenot, “when I was a kid, I thought Hitachi was a French word.

New Orleans Musician Jon Batiste to Headline Louisiana Soirée at French Presidential Palace

French President Emmanuel Macron invited Batiste to take part in the event, part of the “Fête de la Musique,” which takes place in France each summer.

French President Emmanuel Macron invited Batiste to take part in the event, part of the “Fête de la Musique,” which takes place in France each summer.

Jon Batiste at the New Orleans Jazz Fest. Jessica Link/Télé-Louisiane

By Jonathan Olivier

New Orleans Jazz musician Jon Batiste will perform at the Élysée Palace, the official residence of the president of France in Paris, leading a delegation of Louisiana musicians and leaders who are a part of the "Fête de la Musique."

During his visit to New Orleans in December, President Emmanuel Macron invited Louisiana to participate as the guest of honor at his garden party, which will highlight the ties between Louisiana and France. Batiste will play with Ibrahim Maalouf, a French-Lebanese trumpet player, producer and composer, as well as New Orleans-based jazz legends Herlin Riley, Mitchell Player and Mahmoud Chouki.

“We are thrilled that Louisiana has been invited by President Macron for this unique event” said Nathalie Beras, consul general of France in Louisiana. “In the speech he gave during his visit last December, he expressed his desire to include the State in France's future initiatives in favor of Francophonie, such as the forthcoming Cité Internationale de la Langue française in Villers-Cotterêts. This Fête de la Musique is a strong sign of our deep cooperation in many areas, including music, of course, and I'd like to thank Greg Lambousy, Executive Director of the New Orleans Jazz Museum, for his help putting together this exceptional group of New Orleans talent.”

The festival was founded in 1982 as an event where people are invited to play music outside, such as in public spaces or their neighborhoods. New Orleans Jazz Museum Executive Director Greg Lambousy noted that with this invitation, France and Macron are shining a light on the rich culture of New Orleans. “Music and cinema are intertwined,” he said. “Jon Batiste will perform with iconic New Orleans musicians Herlin Riley, Mitchell Player and Gallatin Street Records artist, Mahmoud Choucki, helping to strengthen ties between the two cities in music and film production.”

Meet the People Building a Bilingual Economy in Louisiana

Across Louisiana, there are businesses supporting a French and Creole-speaking economy by offering jobs to locals and catering to tourists from France, Canada, and beyond.

Across Louisiana, there are businesses supporting a French and Creole-speaking economy by offering jobs to locals and catering to tourists from France, Canada, and beyond.

Bryan Dupree co-founded Beausoleil Books in 2020 in order to bridge Louisiana’s culture and those throughout the world. Jonathan Olivier/Télé-Louisiane

This article is Part 3 in a series on French in Louisiana. Part 1, which explains the complexities of French immersion in Louisiana, is available here. Part 2, which explores how former immersion students are creating a French environment in Louisiana, is available here.

By Jonathan Olivier

It was a simple stroll through downtown Lafayette in 2020 that convinced Bryan Dupree and his husband James Colvin to open an independent bookstore. The couple had walked by a group of French tourists who were looking for a place to buy a postcard and have some wine, with service in French.

At the time, Lafayette didn’t have a local bookstore—something that Dupree, who has a degree in French literature, thought was badly needed. Service in French, although available at a few establishments, also wasn’t always easy to find. So, Dupree and Colvin, along with two friends, opened Beausoleil Books in October 2020 to meet both of those needs.

“The idea was that French people from abroad could come and learn about French culture in Louisiana and Louisiana French speakers could learn about the breadth of French that is abroad,” Dupree said. “So, my idea was that we would have a French section that would showcase Louisiana French authors, which it does. And then also showcase new and rising talent in francophone countries around the world, which we do.”

Dupree curates this French book section, called “Le coin francophone,” which promotes this sort of cultural exchange through literature that he said opens up the world to the various groups of francophones—local and from abroad—in Lafayette.

In addition to French-speaking employees, Beausoleil includes bilingual signage and a curated section of books in French. Jonathan Olivier/Télé-Louisiane

At Beausoleil, there are often a myriad of French events like poetry readings and book presentations by French-speaking authors. Beausoleil is usually staffed by at least one francophone who either works in the bookstore or the adjacent Whisper Room, which is a bar.

“I think it's important to provide an opportunity where people can use their French practically,” Dupree said. “That opportunity was given to me to speak in French and be paid to do it when I was a tour guide at Laura Plantation. And I would like to give that opportunity to more people, too.”

Building a Diversified Economy

In 2021, the West Baton Rouge Museum in Port Allen rebranded with a specific focus on highlighting French and Louisiana Creole in partnership with Télé-Louisiane. Angelique Bergeron, the director at the museum who speaks French and Louisiana Creole, said they have trilingual and bilingual signs across the museum grounds. Museum guides, like André St. Romain, offer tours in French. The museum also hosts French-speaking events, such as the Café Français that takes place once a month.

“We just wanted to create a space where people could come together, speak the languages, celebrate the languages and culture, and also come and find work or do something in the languages,” Bergeron said.

Bergeron noted that businesses that offer services in French work toward two goals: to cater to the large numbers of French-speaking tourists that come to Louisiana each year, and also to offer opportunities to local francophones. “My kid is in French immersion in first grade,” she said. “We’ve got a ways to go, but hopefully there'll be jobs for her in French when she gets older.”

André St. Romain is one of the francophone employees at West Baton Rouge Parish Museum, who is capable of giving tours to visitors in French. Ethan Castille/Télé-Louisiane

Bergeron pointed to efforts such as French immersion programs that are creating a pool of francophones that will eventually be looking for work. Bergeron said the upside to hiring Louisiana francophones is that, at the museum, her staff is also capable of catering to the influx of tourists from France and Canada.

According to the Louisiana Department of Culture, Recreation and Tourism, in 2021 the travel and tourism industry was Louisiana’s fifth highest employer, and France and Canada often top the list of travelers. Due to Louisiana tourism advertisements that target francophone visitors, French-speaking tourists are often expecting services in French, yet they are often disappointed at the lack of them, according to Lawson Ota who owns Tours by Marguerite in New Orleans.

Lawson, who offers tours in English, French and Creole, is an advocate for investing more in institutionalizing Louisiana’s heritage languages—hiring francophones or creolophones at restaurants, hotels, hospitals and more. For him, this will only attract more tourists to grow an already powerful economic force. But, he said, getting there will require hard work.

“If we want this industry to grow and for Louisiana French and Louisiana Creole to have futures, the government must understand that it’s not only an opportunity to make money,” he said. “It’s necessary to work and to make investments.”