Acadian Musicians Lisa Leblanc, Les Hay Babies Find Inspiration in Louisiana

The New Brunswick-based artists return to Louisiana this month to play at Festival International de Louisiane. The region, although separated by thousands of miles and hundreds of years of cultural history, still feels like home.

The New Brunswick-based artists return to Louisiana this month to play at Festival International de Louisiane. The region, although separated by thousands of miles and hundreds of years of cultural history, still feels like home.

in 2018, Lisa LeBlanc played at Festival International de Louisiane. Photo courtesy of David Simpson

By Jonathan Olivier

Acadian musician Lisa LeBlanc first visited Louisiana in 2015 to play at Festival International de Louisiane, one of the state’s biggest music festivals. Later that year, she returned for Blackpot Festival where she camped out for a week at Blackpot Camp in Eunice with other musicians from Louisiana and afar.

Louisiana’s music, food, culture and regional French dialect left an indelible mark on the award-winning musician from New Brunswick, so much so that the Bayou State has become a place of inspiration.

“I love Lafayette and it makes me think of Moncton [New Brunswick],” LeBlanc said. “From the first moment that I arrived in Louisiana, it was like I was back at home due to the similarities and the music. There are a lot of similarities between us, the Acadians of the north, and the Acadians of the south.”

LeBlanc is returning to Louisiana this month to play at Festival International de Louisiane for the fifth time. While past appearances have featured her self-described “trash rock” folksy sound, this year she’ll also play songs from her latest album “Chiac Disco” that she released in 2022. Her new music is devoid of banjo and more reminiscent of funk genres from the ‘60s or ‘70s.

LeBlanc returns to Festival International this year, taking the stage Friday and Saturday night. Photo courtesy of David Simpson

“Honestly, I’m really flabbergasted by the reaction to this album,” she said. “We didn’t really know what would come of it. Because, honestly, this kind of album kind of came out of nowhere. It’s super different from what I’ve done in the past.”

Although LeBlanc’s sound has shifted with Chiac Disco, the album’s vibe is not much of a departure from past hits like “Aujourd’hui ma vie c’est d’la marde”—LeBlanc’s new music still showcases her voice’s unique tone, as well as her vibrant personality. Chiac Disco has been a hit with fans across the francophone world, bringing her to Europe to tour several times since the album’s release.

“All of a sudden, I’m finding myself with such a magnificent reception,” she said. “I couldn’t be happier with everything. We are really lucky.”

The Acadian group Les Hay Babies, composed of Vivianne Roy, Julie Aubé and Katrine Noël, also from New Brunswick, will return to Festival International this year for the second time. Like LeBlanc, during the group’s previous trips to the state, it was easy to find similarities between their culture and Louisiana.

“I find that in Louisiana, there are so many familiarities,” Roy said. “It’s as if we could enter a totally parallel world.”

Noël added: “We say all the time that our friends we make who are from Lafayette, it’s like, ‘This is the Louisiana version of someone from back home.’ It’s like everyone has a Louisianan or Acadian counterpart.”

Les Hay Babies return to Festival International de Louisiane this year for the second time. Photo courtesy of Marc-Étienne Mongrain

The group rented a space for a week in Henry, near Erath, Louisiana, in order to record their next album, using the region as inspiration. The trio, which normally plays rock, has no plans for what this new record will sound like—they’re waiting on motivation from Louisiana’s countryside and plan to cut a few songs with local musicians.

“If there are any people who want to come talk to us in French after our show, if anyone sees us at the festival, or if anyone wants to tell us some stories, we’ll take any inspiration that we can have for our album,” Noël said.

Festival International de Louisiane kicks off on April 26, ending on April 30. The event is free and sprawls across downtown Lafayette. Lisa LeBlanc will play on April 28 at 8:30 p.m. at the Scène Laborde Earles Fais Do Do, and on April 29 at 6 p.m. at the Scène LUS Internationale. Les Hay Babies will play on April 29 at 4:30 p.m. at the Scène Tito’s Handmade Vodka, and on April 30 at 3:30 p.m. at the Scène Laborde Earles Fais Do Do.

For more information on Festival International de Louisiane, find the full line up here.

Cajun Mardi Gras in the Prairie of Faquetaique

Lafayette-based photographer Kristie Cornell has participated in the Faquetaique Courir de Mardis since 2009. This year, she captured the tradition in a series of analogue photos.

Lafayette-based photographer Kristie Cornell has participated in the Faquetaique Courir de Mardis since 2009. This year, she captured the tradition in a series of analogue photos.

By Kristie Cornell

In 1997, I attended and photographed my first Courir de Mardi Gras, which was the Tee Mamou/Iota women’s run. In the years following, I continued on and off to follow and photograph various courirs, including those in Soileau, Elton, Jennings and Eunice, but always as a spectator. In 2009, I participated in the Faquetaique Courir de Mardi Gras, carrying my camera and capturing images from the perspective of a participant rather than that of a bystander.

Over the years, my personal photography had been a mix of film and digital, but for speed and ease I always opted to carry my digital camera when photographing at Faquetaique. By 2020, I had grown tired of digital images and had fully transitioned back into analog photography. So, in 2023, I decided to try to shoot the courir on film with my medium format Hasselblad 500c. This is no easy task–carrying a heavy camera while walking all day, and framing images on the ground glass while wearing a mask. But I love every minute of it.

I have continued to run Faquetaique every year since 2009, always photographing with the intention of documenting my friends and the ridiculousness that happens during the course of a Mardi Gras day. In capturing these images each year, I hope to preserve the memory of the day for all of us who actively participate in upholding our culture and traditions.

Kristie Cornell is a self-taught photographer living and working in Lafayette, Louisiana. Her work explores her relationship to the natural and cultural landscapes of her native Louisiana and the South, as well as connections made to places she explores while traveling. Her photographs have been published in several books and as album artwork, and her work has been shown at many galleries across Louisiana. Additional work can be found at www.kristiecornell.com, or on Instagram at @kccornell.

An Introduction to Louisiana French

Louisiana French is a collection of varieties spoken by Native Americans, Africans, Acadians and Europeans since the 18th century.

Louisiana French is a collection of varieties spoken by Native Americans, Africans, Acadians and Europeans since the 18th century.

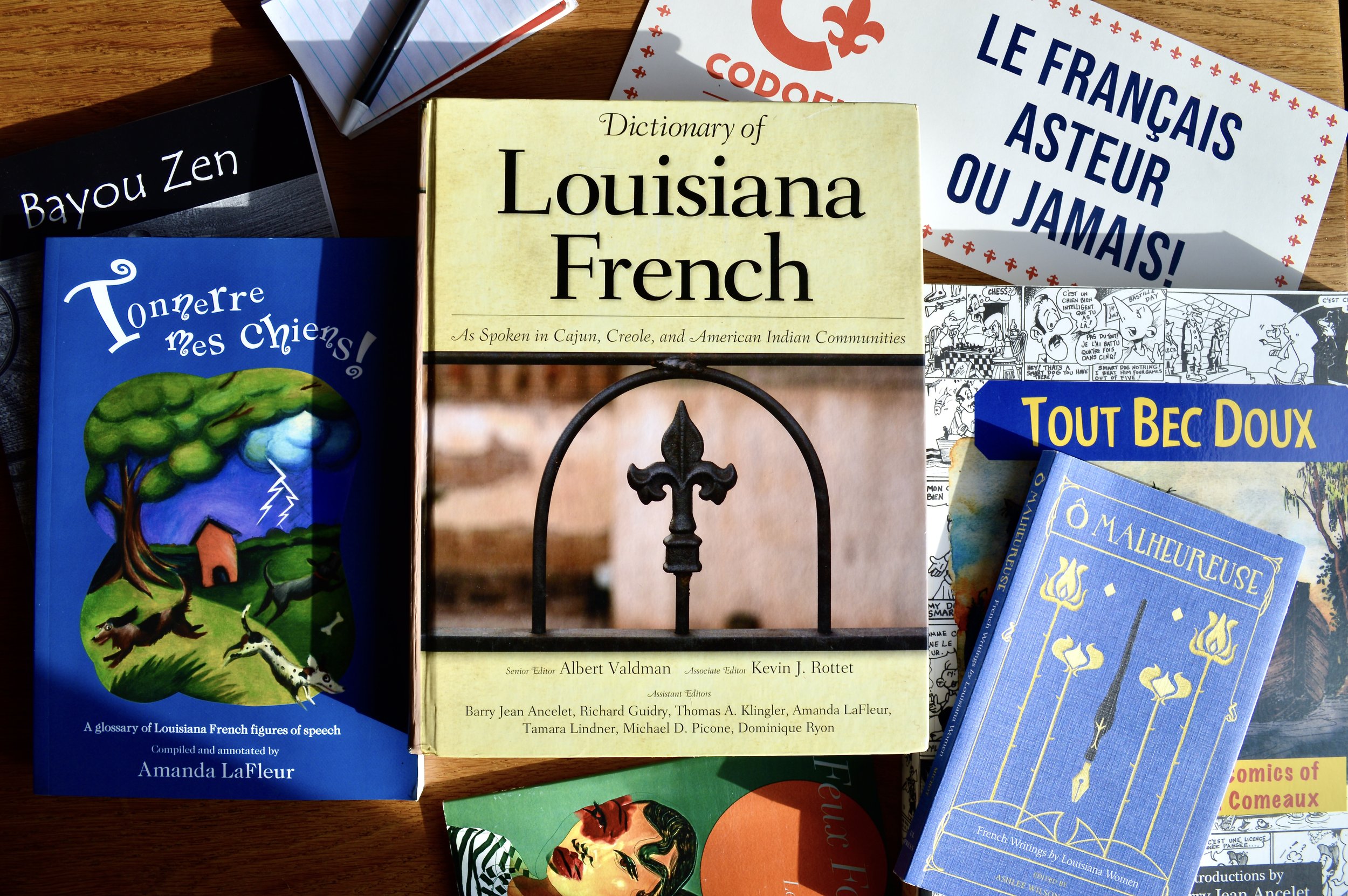

The “Dictionary of Louisiana French: As Spoken in Cajun, Creole, and American Indian Communities” serves as a valuable resource for francophones wishing to learn. Jonathan Olivier/Télé-Louisiane

By Jonathan Olivier

It was always those little phrases my mom or dad would utter that stuck with me the most. Viens manger or ferme la porte. Scattered throughout their English were words rooted in Louisiana French, the byproduct of their upbringings—their parents are native speakers of French, while my mom’s mother also grew up with Louisiana Creole.

Yet, for the majority of my life French only played a minor role—the result of decades of Americanization, economic changes in Louisiana, and the state’s 1921 constitution that allowed only English to be used in classrooms. A heritage and linguistic chain had been severed, one that linked me to my first francophone ancestors in North America who came in the 1600s to Nova Scotia, Canada, in the region they called Acadia.

The journey to reclaiming my family’s heritage language has been a long one. I have taken classes in high school, college and participated in French immersion in Canada. I traveled to Quebec and New Brunswick. I began to hardly speak English to my grandparents, embracing and better understanding the French of my family, of my home. In a region now dominated by English, I have to work at it every day. I make mistakes, then learn from them. At times, it feels more like work than reconnecting with my past. And I’d imagine this is true for most folks who have taken that step toward reclaiming a heritage language.

Although, at other points, I forget the grind and the pressure to hold on to French as the number of native speakers continues to decline. I don’t worry so much about the mistakes I make. Speaking French feels effortless. The language of my ancestors opens up doors I didn’t know were there. Ideas, opportunities and friends arrive in my life that otherwise would’ve been unknown to me. For me, speaking French has evolved past a journey of reclamation, but now it’s an integral part of my existence, a powerful piece of my identity.

For those wanting to take the first step to reconnecting with French, or even for those who are just curious about it, this guide is meant to provide you with an introduction to several aspects of it. This article is not exhaustive at all, meaning I’ve left out more than I could include. But I hope that this provides you with a start, or perhaps even inspiration to keep going in your journey to reclaim this heritage language as your own.

What is Louisiana French?

Louisiana French, also commonly called Cajun French, is an umbrella term for a collection of varieties of French that was first spoken in the region by francophone groups such as colonial French settlers, Canadians, Haitian Creoles and Acadians. French, the dominant language of Louisiana for many generations beginning in the 18th century, was also adopted by many of Louisiana’s Native American groups, enslaved Africans and free people of color, as well as German, Spanish and English immigrants.

Today, the predominant populations that continue to speak French as their first language consist of Bayou Indians (Native Americans of Lafourche and Terrebonne parishes), Creoles, and Cajuns. All three of these groups descend to varying extents from the founding peoples of Louisiana.

Over the decades, French in Louisiana was shaped by these different ethnic groups. For example, there are many indigenous elements in Louisiana’s lexicon, such as chaoui (raccoon), a Choctaw word, or plaquemine (persimmon), from an Algonquian language. The words gombo and févi (both can refer to okra) are derived from African peoples and lagniappe comes from Spanish in South America.

Other notable features are archaic structures that Louisianans have retained but that have mostly disappeared from today’s international French. For example, chevrette (shrimp) is an older French word that remained in Louisiana due to isolation while in France today people use crevette, more recently adopted from the Normans. Still, Louisianans adapted words to refer to new inventions like cars, which in Louisiana and Quebec is char and in France it is voiture.

Despite these few lexical variations, French in Louisiana is mutually intelligible with other varieties of French across the francophone world. After all, the French as it’s spoken today in France is only one dialect of the language, just as American English varieties differ slightly from British English.

A Language Continuum

In geographic areas where French has existed alongside Louisiana Creole, there is the notion of a continuum of French and its related varieties, which includes: Louisiana French, Louisiana Creole and international French. A continuum implies some sort of structure involving elements that are similar yet markedly different at the two poles. In this case, it’s easy to think about the three elements existing on a linear plane, with international French and Louisiana Creole at separate ends, then Louisiana French in the middle. These two extreme poles are different on the morphosyntactic level while there is much overlap on the lexical level between Louisiana French and Louisiana Creole. These similarities and differences are incredibly important in Louisiana, where different speech communities regularly interact with one another.

People can be placed on the continuum, depending on the language or variety of French they speak. However, due to the interaction between speech communities, people often have the ability to move back and forth along the continuum depending on who they are speaking with. For example, a French speaker might be able to move more toward Creole on the spectrum if he or she regularly interacts with Creole speakers. This tactic allows different speech communities to effectively communicate.

Although, at one time, Louisiana Creole was categorized as a dialect of French, it is in fact its own language given its unique syntax and grammar, despite its lexical similarities with French. Louisiana’s speech community is further complicated and enriched by the fact that Louisiana Creole is spoken not only by people who identify as Creole but also by many Cajuns. While Louisianans may refer to the language they speak as Cajun, Creole, Cajun French, Indian French, Houma French, Creole French, or just French, linguists increasingly use the terms Louisiana Creole or Kouri-Vini, and Louisiana French, in an effort to more accurately identify these two languages within Louisiana’s linguistic continuum.

Variations of French in Louisiana

Herb Wiltz, pictured here in episode 10 of La Veillée, speaks French and Louisiana Creole. Drake LeBlanc/Télé-Louisiane

There are several varieties of French in Louisiana that differ due to an array of factors like geographic location, age, education or even language attrition. Some francophones in southeast Louisiana, particularly in south Lafourche Parish, utilize an aspirated “h” when pronouncing “j” or “g” (j’ai été sounds like h’ai été). Someone might use the word grouiller to mean “to move” to another home, while others will say déménager or even “move,” borrowed from English. In Avoyelles and Lafourche parishes, it’s common for speakers to express “what” by saying qui while other regions of Louisiana employ quoi.

Professor emeritus at the University of Indiana Albert Valdman, in his study “Standardization or laissez-faire in linguistic revitalization,” included an example of a native speaker that, in one paragraph, used five different ways to express they, or the third person present indicative verb form: eux-autres, ça, ils, eusse, and ils with -ont.

Mais sho, eux-autres serait contents, tu les appelle ‘oir, parce que ça travaille tard, eusse a un grand jardin en arrière, et ils travaillont tard, des fois ils sont tard dans la maison. [Well sure, they would be happy, you call them and see, because they work late, they have a big garden in back, and they work late, sometimes they’re in late.]

The study displayed that different age groups tended to stick to different forms of the third person present indicative verb form. For example, 25 percent of people older than 55 tended to use ils, while only one percent of people under 30 used ils—instead, 77 percent of them opted for eusse.

Due to this variation, linguists don’t exactly have a neat definition for French in Louisiana. Instead, it’s best understood as a collection of different varieties that are spoken across the state. Even still, these varieties share a lot in common, so below are some examples that make French in Louisiana unique.

Lexical Items

Ruby and Raymond Danos, pictured here in the sixth episode of La Veillée, are from Cutoff, Louisiana, where they learned to speak French as children at home. Drake LeBlanc/Télé-Louisiane

A lexical item is a word or a sequence of words. Due to Louisiana’s linguistic diversity, its French contains some lexical items unique to the region—although much more are well known in Canada, France or throughout la francophonie. Other lexical items are quite common in French, although they have taken a different meaning in Louisiana due to its isolation from other francophone regions. Here are a few examples:

Un chaoui (indigenous origin)

English: Raccoon

International French: Un raton laveur

Asteur (common in Canada and parts of France)

English: Now

International French: Maintenant

Un char (common in Canada)

English: Car

International French: Une voiture

Une banquette

English: Sidewalk

International French: Un trottoir

Une piastre (common in Canada)

English: Dollar

International French: Un dollar

Une chevrette

English: Shrimp

International French: Une crevette

Un plaquemine (indigenous origin)

English: Persimmon

International French: Un kaki

Des souliers

English: Shoes

International French: Des chaussures

Espérer

English: To wait

International French: Attendre (in France, espérer means “to hope”)

Regional Grammatical Structure

In Louisiana, the grammatical structure, or arrangement of words, can be varied and also unique. While second language learners of French are often quick to pick up lexical items like nouns, it can be harder to incorporate more complex grammatical structures. If you talk to any native speaker of French in Louisiana, chances are you’ll hear these four structures often.

Être après

In international French, the present progressive is être en train de, such as je suis en train de faire quelque chose (I am doing something). However, in Louisiana, this form is être après, such as je suis après faire quelque chose.

Avoir pour

This is a common way to express “to have to” in Louisiana. While other ways of expressing a necessity are also common by using words such as devoir, il faut or avoir besoin, in Louisiana, avoir pour is pretty unique. For example, someone might say, J’ai pour travailler aujourd’hui (I have to work today).

Article-Preposition Contractions

With prepositions, it’s standard in international French to write and say de le as du, or de les as des. Yet, in Louisiana, you’ll often hear speakers avoid these contractions. So, one might say, C’est à cause de le froid j’ai resté dedans la maison (I stayed inside because of the cold).

Subject Pronouns

Typically, native speakers of French in Louisiana follow the same subject pronoun patterns as international French, with a few exceptions. For example, the international French vous is hardly used in Louisiana—only in very formal situations. In the below examples, conjugations that differ from international French are noted.

Je (i)

Tu (you)

Vous (you, used rarely and only in very formal situations)

Il (he)

Elle (she, sometimes pronounced/written as alle)

Nous-autres, On (we)

The more colloquial expression of “we,” expressed by on, has by and large replaced nous in Louisiana. Yet, nous-autres is often used in conjunction with on. For example, Nous-autres, on était dans le clos un tas des années passées. (We were in the fields a lot back then.)

Vous-autres (you plural)

This subject pronoun uses the same verb form as the third person singular il. For example, Vous-autres va à la messe ? (Y’all are going to mass?)

Ils (they, often used to express men and women)

Elles (they, this feminine form is not often used)

Ça, eux-autres, eusse (they)

Eusse is common in southeast Louisiana, such as in Terrebonne and Lafourche parishes. However, it isn’t as common in other parts of Louisiana. While ça and eux-autres are typically used throughout the French-speaking region of the state. These three are typically conjugated using the third person singular verb form. For example, Eux-autres a deux garçons. Mais ça voulait une tite fille itou. (They have two boys. But they wanted a little girl too.)

How to Learn

Abraham Parfait of the United Houma Nation, pictured here in the fifth episode of La Veillée, speaks what people in his community call Houma French or Indian French. Drake LeBlanc/Télé-Louisiane

There are plenty of ways to learn. Online classes taught by local experts are available, and texts that have been compiled by linguists offer valuable information about the dialect. And, of course, one of the best ways to practice is to find a native speaker to learn directly from them. If they’ll allow it, record your conversation and transcribe it, which functions as an intimate way to learn. Below, you’ll find resources to get you started on your journey to learning.

Videos

Les Adventures de Boudini et Ses Amis, a cartoon series in French, produced by Crele Cartoon Company with Télé-Louisiane for Louisiana Public Broadcasting (LPB), which is perfect for beginners or children.

La Veillée, a fifteen-minute weekly news magazine produced by Télé-Louisiane and LPB.

Le Louisianiste, Télé-Louisiane’s newest podcast with a focus on native speakers of French.

Le français louisianais: quoi c’est ça ?, a YouTube video produced by Télé-Louisiane that expains the basics of French in Louisiana.

Kirby Jambon’s French lessons, a series lessons made by Acadiana French teacher Kirby Jambon.

Classes and online databases

Classes hosted by Alliance Française de Lafayette, taught by David Cheramie and Ryan Langley.

Online resources provided by the Department of French Studies at LSU.

Louisiana French Oral Histories, an oral history project complete with interviews of native French speakers and corresponding transcriptions, compiled by the Department of French Studies at LSU.

Memories of Terrebonne, an oral history collection from Terrebonne Parish.

French Tables, which are informal gatherings where francophones get together and chat, are held around the state. This list has been compiled by the Council for the Development of French in Louisiana.

Cajun French Virtual Table Française, a Facebook group dedicated to French.

Cajun French Video Lessons, a Facebook group that posts videos.

Books

Tonnerre mes chiens! A glossary of Louisiana French by Amanda LaFleur

Dictionary of Louisiana French: As Spoken in Cajun, Creole, and American Indian Communities by Albert Valdman et. al

Cajun French Dictionary and Phrasebook by Jennifer Gipson and Clint Bruce

Sources:

Ancelet, B. J. (1988). "A perspective on teaching the “problem language” in Louisiana.” The French Review, 61,

345-356.

Ancelet, B. J. (2007). “Negotiating the mainstream: The Creoles and Cajuns in Louisiana.” The French Review,

80, 1235-1255.

Blyth, C. (1997). “The Sociolinguistic Situation of Cajun French: The Effects of Language Shift and Language

Loss.” In A. Valdman (Ed.), French and Creole in Louisiana (pp. 25-46). New York: Plenum Press.

Brown, B. (1993). “The social consequences of writing Louisiana French.” Language in Society, 22, 67-101

Dajko, Nathalie (2012). “Sociolinguistics of Ethnicity in Francophone Louisiana.” Language and Linguistics

Compass, 6, 279-295.

Dajko, Nathalie; Carmichael, Katie (2014). “But qui c’est la différence ? Discourse markers in Louisiana French:

The case of but vs. mais.” Language in Society, 43, 159-183.

Valdman, Albert (2000). "Standardization or laissez-faire in linguistic revitalization: The case of Cajun French.”

Indiana University Working Papers in Linguistics 2: The CVC of Sociolinguistics: Contact, Variation, and

Culture, 127-138.

Valdman, Albert; Picone, Michael D (2005). “La situation du français en Louisiane.” In A. Valdman et. al, Le

Français en Amérique du Nord: État présent (pp. 143-165). Les Presses de l’Université Laval.

In August, École Pointe-au-Chien to Open Kindergarten, First Grade

The board of directors convened at its first meeting on Monday, March 13, where it approved hiring two French teachers for the inaugural school year.

The board of directors convened at its first meeting on Monday, March 13, and it approved hiring two French teachers for the inaugural school year.

The board of directors of École Pointe-au-Chien voted on several measures during its first meeting on Monday, March 13. Kezia Setyawan/WWNO

By Jonathan Olivier

The board of directors of École Pointe-au-Chien, Louisiana’s newest French immersion school, located in Pointe-aux-Chênes at the crossroads of Terrebonne and Lafourche Parishes, voted to open enrollment for children seeking entry to kindergarten and first grade for the inaugural school year that will begin in August. The board also voted to recruit two French teachers in coordination with the Council for the Development of French in Louisiana and the Louisiana Department of Education.

"Not only is this going to bring a school back to our community, but it will be a beginning for bringing the language back to the community,” said Christine Verdin, council member of the Pointe-au-Chien Indian Tribe. “We will begin with elementary but will also eventually offer adult classes so interested parents can learn French too. Our goal is to hear more French in and throughout our community."

The board voted to begin soliciting interest from parents of prospective students. As permitted by applicable state law, preference in enrollment will be given to families who live in Pointe-aux-Chênes, Isle de Jean Charles or former residents who were displaced due to Hurricane Ida or relocation from the island by the state, as well as the families of former students of Pointe-aux-Chênes Elementary. If spots are still available, enrollment will then open as a lottery to students from other parts of Lafourche and Terrebonne parishes with weighting for children of French immersion teachers at the school, those with parents or grandparents from Pointe-aux-Chênes or Isle de Jean Charles, and anyone with family members with a demonstrated background or interest in Louisiana French.

Beginning with the 2023-2024 school year, École Pointe-au-Chien will be located in the Knights of Columbus building in upper Pointe-aux-Chênes. Eventually, École Pointe-au-Chien will move to the site of the former Pointe-aux-Chênes Elementary building, which closed in 2021 due to a decision by the Terrebonne Parish School Board and then was damaged by Hurricane Ida. Renovations are expected to begin on the building later this year.

“The board is working closely with the Division of Administration, the Department of Treasury, and state legislators to find the most effective ways to expend funds allocated to the school to renovate the provisional and final school buildings as well as other necessary investments in curriculum, finances, and administration,” said Will McGrew, Télé-Louisiane CEO, who was elected as interim president until the full board is appointed.

At Monday’s meeting, nine board members were present after being appointed by their respective state agencies or Indian Tribes (including the Consul General of France in Louisiana Nathalie Beras, ex officio, in an advisory capacity). In total, there will be 13 members serving on the board.

Initial funding for École Pointe-au-Chien comes from $3 million allocated by the state legislature, which voted in 2022 to pass HB 261 (Act 454), authored by Speaker Pro Tempore Tanner Magee, R-Houma, that created the school and established an independent governing board. Board members reviewed next steps for spending some portion of the $3 million by the end of the state’s fiscal year on June 30, and it is coordinating with legislators on rolling over the remaining funding to next fiscal year, which begins July 1.

The board also voted to create an online form for parents to express interest in enrolling their children who live in the target enrollment area.

“We have a lot of work ahead of us, but we are proud to be making history in creating the first French immersion school in Lafourche and Terrebonne parishes, the first immersion school serving a predominantly Native population, and the first immersion school that will teach our local Cajun and Indian French dialects of French,” McGrew said. “We are grateful for the overwhelming support from the legislature and other stakeholders in making this school a reality for Pointe-aux-Chênes and a model for communities across the state.”

Those interested in enrolling their children at École Pointe-au-Chien can complete the parent interest form or contact ecolepointeauchien@gmail.com.

La Veillée Returns to LPB for Spring Premiere on March 16

The 8-episode series explores French programming on KRVS public radio, the Isleños of Louisiana, the tradition of boucheries, and much more.

The 8-episode series explores French programming on KRVS public radio, the Isleños of Louisiana, the tradition of boucheries, and much more.

Filming for season 1.2 of La Veillée has been underway since February, featuring reporting in the field with francophones from across Louisiana. Drake LeBlanc/Télé-Louisiane

By Jonathan Olivier

La Veillée, a weekly news show produced by Télé-Louisiane with Louisiana Public Broadcasting (LPB), returns with more stories that dig deeper into the rich cultural layers of the region. The spring half of season 1 features French-language content alongside a special episode in Spanish documenting the Isleño community of Louisiana and another episode partially in Creole focused on the Louisiana Creole language.

“La Veillée is unique not only because it is in French, but also because we visit communities that are too often forgotten in mainstream coverage and we focus on stories that matter to people across Louisiana regardless of ethnic, political, or regional background,” said Télé-Louisiane CEO and co-founder Will McGrew, who is an executive producer of La Veillée.

La Veillée is the first weekly television program produced entirely in Louisiana French in over 30 years. It airs for 15-minutes on Thursdays at 7:45 p.m. on LPB and online. The spring season premiers on March 16 with a finale on May 4, featuring in-the-field reporting and interviews, and hosted by McGrew, Drake LeBlanc and Caitlin Orgeron. The eight episodes from the fall season are available online at lpb.org/laveillee.

The Thursday night premier will focus on French-language programming hosted on Acadiana’s NPR public radio affiliate KRVS. The station is home to Blake Miller’s La Lou Juke Box, Megan Brown Constantin’s Encore and Cedric Watson’s La Nation Créole.

“We have admired KRVS’s historic French programming over the years and were thrilled to see the return of Bonjour Louisiane with Ashlee Michot,” McGrew said. “Interviewing some of the young talent at the station for our spring season premiere was inspiring, informative and fun.”

Throughout the season, La Veillée episodes will explore a variety of topics:

A special Spanish-language episode focused on the Isleños of St. Bernard Parish

An episode focused on revitalization efforts underway for the Louisiana Creole language

Interviews with Lafayette-area-based musicians Jo Vidrine, Kelli Jones and Jourdan Thibodeaux

A look at the efforts to keep French alive with reports on two French immersion schools: LeBlanc Elementary, which is the first and only immersion school in Vermilion Parish, and École St. Landry, a French immersion charter school in St. Landry Parish

An exploration of the traditional boucherie through the decades-old Fête du Cochon, an annual celebration in Golden Meadow

Also airing on LPB in March is the animated cartoon series Les Aventures de Boudini et Ses Amis, created by the Creole Cartoon Company with Télé-Louisiane. Boudini premiered online in Jan. 2021, and the first season was funded with support from the Louisiana Consortium of Immersion Schools, CODOFIL, the Atchafalaya National Heritage Area, and the Louisiana Endowment for the Humanities. The move to LPB highlights the ongoing partnership between the network and Télé-Louisiane to strengthen French language programming in the state.

“Our partnership with Télé-Louisiane has been a wonderful way to share the stories of the French-speaking communities in Louisiana,” said Linda Midgett, LPB executive producer. “This has always been an important part of LPB’s mission and we are grateful for this collaboration.”

Join Millions Across the Americas to Celebrate the Mois de la Francophonie

Sylvain Lavoie of the Centre de la francophonie des Amériques discusses the importance of the francophone communities of the Americas, as well as his organization’s benefits to Louisianans.

Sylvain Lavoie of the Centre de la francophonie des Amériques discusses the importance of the francophone communities of the Americas, as well as his organization’s benefits to Louisianans.

The Centre de la francophonie des Amériques builds relationships with francophones and francophiles across the continent. Centre de la Francophonie des Amériques

This post is sponsored by the Centre de la francophonie des Amériques.

By Jonathan Olivier

The Centre de la francophonie des Amériques was created in 2008 by the Government of Quebec to build relationships with the francophones and francophiles across the continent. This year, the Centre is celebrating its 15th anniversary. The Centre also annually celebrates the “Mois de la Francophonie,” which aims to promote the French language in this magnificent context of cultural diversity.

In order to better understand the Centre’s role in the Americas, we caught up with Sylvain Lavoie, President and CEO of the Centre, to ask him about his organization and what’s going on throughout the Mois de la Francophonie. Plus, we find out how Louisianans can get involved and become a member.

Q: What is the role of the Centre in “la Francophonie?”

A: The Centre supports dialogue and encourages people, communities and groups interested in the Francophonie to come together in a spirit of solidarity, discovery and sharing. Over the past 15 years, the Centre has developed a wide network through its actions on the ground, all over the continent, which comprises thousands of members.

To reach its clientele, the Centre collaborates with partners from various backgrounds who contribute to enhancing the French language and francophone culture, as well as sharing a diverse and dynamic Francophonie. We have many partners in Louisiana, and we are very proud of them! The projects carried out are promising and unifying for a diverse and dynamic Francophonie.

Sylvain Lavoie, President and CEO of the Centre de la francophonie des Amériques. Centre de la Francophonie des Amériques

Q: Do any Louisianans work with the Centre?

A: The Centre is very pleased to have on its Board of Directors Peggy Feehan, executive director of the Council for the Development of French in Louisiana (CODOFIL). She succeeded Zachary Richard, who has held the title since the Centre was founded, and who is now an honorary member of the Centre for his outstanding contributions over the years.

Q: What are the Centre’s flagship programs?

A: The Centre offers at least one intensive training program per year that brings together participants from the Americas. Over the years, many people from Louisiana have participated in these programs. The bonds that are forged last over time and these people become involved in their communities. These initiatives enable the discovery, development and celebration of the Francophonie of the Americas.

These three programs are:

Forum des jeunes ambassadeurs de la francophonie des Amériques

Parlement francophone des jeunes des Amériques

Université d’été sur la francophonie des Amériques

Q: Do any of the Centre’s programs take place in Louisiana?

A: The 2023 edition of the “Université d'été sur la francophonie des Amériques” will be presented in collaboration with the University of Louisiana at Lafayette (ULL), from May 22 to 27, 2023. This is the first time a Centre Signature Program has been held outside of Canada! Several partners will join this event, including CODOFIL and the Agence universitaire de la Francophonie. Nathan Rabalais, associate professor of Francophone studies at ULL, will accompany this group during this intensive training.

Q: What is the “Bibliothèque des Amériques?”

The Bibliothèque des Amériques is a unique tool that provides free access to thousands of books for all francophones and French learners in the Americas. It includes:

A catalog of over 17,000 digital books of French-speaking authors from the Americas, available for loan;

Literary news: news and portraits of authors

Suggestions for reading

Dynamic programming including “Rendez-vous littéraires”

An educational area to support primary and secondary teachers in French as a first, second or foreign language

To learn more, click the link: bibliothequedesameriques.com

Q: What is the Francophonie of the Americas?

A: The francophone presence in the Americas is a historical and geographical reality that varies from one community to another. It has 33 million francophones and francophiles. Across the continent, in sometimes isolated communities, the French heritage resonates. From the shores of Acadia to the vast expanses of the prairies of western Canada, to Louisiana and the Caribbean, French in the Americas continues to resonate, to make people laugh, cry, dance, sing and live.

There are 33 million francophones and francophiles on the continent. Centre de la francophonie des Amériques

Q: What is the “Mois de la Francophonie?”

A: Throughout the month of March, the Centre is partnering with various partners and collaborators to share the dynamism and richness of the Francophonie of the Americas. The Centre can present activities that bring together francophones from the Americas, such as conferences, round tables, film screenings, reading proposals, literary meetings, competitions, and more.

Q: When is the International Day of the Francophonie?

A: Since 1990, francophones and francophiles from all continents have celebrated the International Day of the Francophonie every March 20. This event was created in 1988 to celebrate the French language and its 300 million speakers worldwide. It is an opportunity for all individuals to celebrate by expressing their solidarity and desire to live together, in recognition of their differences and diversity!

The date of March 20 was chosen to commemorate the signing of the treaty that created the Agence de Coopération Culturelle et Technique, the precursor to today’s Organisation internationale de la Francophonie, on March 20, 1970 in Niger.

To learn more about the “Mois de la Francophonie” in 2023, click here: Mois de la Francophonie

Q: How can Louisianans take advantage of the many resources that the Centre has to offer?

A: The Centre has thousands of members and is very pleased to have people from Louisiana among them! To connect to the Francophonie of the Americas and use the Centre’s resources, you must become a member and it’s free. You are just one click away from joining us!

Individual members receive the Centre’s newsletter and benefit from:

Espace M, a platform that offers exclusive content to members;

Bibliothèques des Amériques with over 17,000 eBooks

Centre programs, activities and competitions;

The opportunity to participate in the Centre’s democratic process.

A Guide to Festivals in Louisiana: Music, Food and Culture

A list of more than a dozen festivals in Louisiana that highlight the unique culture of the Bayou State.

A list of more than a dozen festivals in Louisiana that highlight the unique culture of the Bayou State.

Donny Broussard and the Louisiana Stars at Festivals Acadiens et Créoles in 2022. Ethan Castille/Télé-Louisiane

By Jonathan Olivier

One of the best ways to get acquainted with the traditions of Louisiana is to attend a few of the many festivals that occur throughout the year. Some pay homage to regional traditions, others local musicians or foodways—but they all highlight the state’s unique cultural flair. Most festivals occur when there’s a break in the sub-tropical heat, usually in the spring months of March and April, as well in the fall in October. Our list compiles more than a dozen festivals in Louisiana that celebrate the music, food and culture of the Bayou State.

Music

Festivals Acadiens et Créoles in 2022. Ethan Castille/Télé-Louisiane

New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Festival

New Orleans - April/May

Known affectionately around Louisiana as Jazz Fest, this is one of the biggest festivals in Louisiana of the year. Multiple stages showcase musical genres like blues, Cajun, folk, rock, rap, and Caribbean played by artists from local staples such as Beausoleil and the Preservation Hall Jazz Band. The festival also attracts big names like Santana, The Lumineers and Ed Sheeran. Not only a music festival, Jazz Fest celebrates the region’s culture through food and crafts during two action-packed weekends. Tickets are required with several packages available to purchase.

French Quarter Festival

New Orleans - April

This festival, normally held each year in April the weekend before Jazz Fest, highlights the best of New Orleans’ French Quarter culture. Performances by acts like Irma Thomas and Rebirth Brass Band dot the neighborhood, complete with well-known food vendors serving up Creole food. Started in 1984, French Quarter Festival is completely free and open to visitors from around the world.

Essence Festival of Culture

New Orleans - July

Essence Fest was first hosted in 1995 to celebrate the 25th anniversary of Essence, a magazine aimed at African-American women. Today, it has grown to become one of the largest African-American cultural and music events in the country. Typically taking place over the Fourth of July weekend, the festival draws acts like Beyoncé and Mary J. Blige to the Caesars Superdome. The Essence Expo features workshops and presentations, while vendors display art, food and culture from throughout the African diaspora. Tickets are required for entry.

Festival International de Louisiane

Lafayette - April

This five-day, free event in downtown Lafayette is unlike any other in Louisiana. Festival International is a celebration of the region’s unique mix of cultures, with musical acts coming from the regions that shaped south Louisiana, such as France, Canada and Africa, but also others from around the world. Usually occurring at the end of April, Festival International also features an array of local Cajun and Creole food.

Baton Rouge Blues Festival

Baton Rouge - April

This festival in Louisiana’s capital city is free and it pays homage to a distinct genre of music—swamp blues—that developed in the area in the 1950s by artists like Slim Harpo. Originating in 1981 on the campus of Southern University, today the Baton Rouge Blues Foundation produces the festival, bringing together acts from around the world.

Festivals Acadiens et Créoles

Lafayette - October

In 1974, francophone activists organized the Tribute to Cajun Music Festival, birthing today’s festival that has become the largest celebration of Acadiana’s Cajun and Creole culture in Louisiana. The festival’s line up includes local favorites like Wayne Toups and the Lost Bayou Ramblers, as well as the best in the region’s cuisine. Festivals Acadiens et Créoles is typically held each year in October in Girard Park and entry is free.

Food

A few of the various food vendors at Festivals Acadiens et Créoles in 2022. Ethan Castille/Télé-Louisiane

Jambalaya Festival

Gonzales - May

This small town south of Baton Rouge bills itself the Jambalaya Capital of the World. Since 1968, thousands of people have flocked here to sample all sorts of jambalaya—a Creole dish of rice, sausage and meat—that results from the many vendors and the festival’s cookoff. Typically held during a weekend in late May, this free festival also features live music, carnival rides, a race and a pageant.

Etouffee Festival

Arnaudville - April

The Etouffee Festival celebrates crawfish etouffee—mudbugs that are “smothered” down in a gravy. Arnaudville is home to a sizable population of native Louisiana francophones, as well as cultural hub Nunu Arts and Culture Collective. Typically taking place in late April, this festival features live music, carnival rides and a cookoff.

Amite Oyster Festival

Amite - March

This small town on the north shore of Lake Pontchartrain traces its connection to the oyster industry to 1949 when Carlo’s Oyster House opened up. In 1976, this celebration was birthed as Amite Oyster Day and today it’s held in March—one of the only festivals in Louisiana celebrating this unique part of the state’s culture. The free event features a cookoff, music and plenty of oyster dishes.

Breaux Bridge Crawfish Festival

Breaux Bridge - May

In early May at Parc Hardy in Breaux Bridge, the Crawfish Festival welcomes vendors offering crawfish prepared in just about every way imaginable: etouffee, boiled, boudin, bisques and more. The free event always features local Cajun and Zydeco artists, along with a parade and crawfish eating contest.

Scott Boudin Festival

Scott - April

Scott is known as the Boudin Capital of the World for good reason—it’s home to a concentration of establishments like Billy’s, Don’s, Kartchner’s and Best Stop. The Boudin Festival celebrates all things boudin—a sort of sausage filled with rice and pork—supplied by local vendors. This free event usually occurs in April and tickets are required for entry.

Ponchatoula Strawberry Festival

Ponchatoula - April

Ponchatoula, located on the north shore of Lake Pontchartrain, is the Strawberry Capital of the World. Fittingly, since 1972 this festival has celebrated all things strawberries, typically in April. This ticketed event features a parade, live music and plenty of opportunities to sample local strawberry products from farmers of the region.

Giant Omelette Celebration

Abbeville - November

In the 1980s, members of the Abbeville Chamber of Commerce went to Bessieres, France, where they witnessed an omelette festival. While in France, they were knighted as members of a brotherhood of chefs, called the confrerie, and Abbeville hosted its own omelette festival in 1984–one of seven such festivals around the francophone world. Each year, the chefs use thousands of eggs, along with hundreds of onions and other ingredients, to cook the massive egg dish on a 12-foot skillet in the middle of town that is then eaten by participants.

French Food Festival

Larose - October

This festival celebrates the French roots that permeate part of Louisiana’s culinary history, a legacy that includes contributions from many ethnic groups like West Africans, Native Americans, and Spanish Caribbean peoples. Hosted by the Larose Civic Center as a fundraiser, the French Food Festival features an array of dishes that have put Louisiana cuisine on the map: gumbo, etouffee, jambalaya and boudin.

Culture

Most of the festivals in Louisiana feature live music and dancing. Ethan Castille/Télé-Louisiane

Louisiana Shrimp and Petroleum Festival

Morgan City - September

Located near the mouth of the Atchafalaya River, Morgan City plays host to this festival with roots dating back to a blessing of the fleet in 1936. Today, the blessing of the fleet remains a critical part of this free festival that takes place in September, paying homage to the shrimpers and oil field workers of the region. There’s also music, a car show, parade and a 5K.

International Rice Festival

Crowley - October

Held every third weekend in October since 1937, the Rice Festival is one of the oldest festivals in Louisiana. This region of the state is known for its abundance of rice agriculture, and this festival pays homage to the industry and its importance to Louisiana. Tickets are required for entry, allowing you access to live music with acts like Wayne Toups.

Rayne Frog Festival

Rayne - May

This small town in southwest Louisiana is known as the Frog Capital of the World. Although Rayne was named after B.W.L. Rayne, a railroad employee, it’s close to the Louisiana French word “raine,” which means frog. In the 20th century, the town was the largest exporter of frog legs in the world. At this festival, you can expect plenty of frog dishes and frog races along with live music and pageants.

Rougarou Fest

Houma - October

This festival celebrates the folklore of south Louisiana, owing its name to the region’s tale of a werewolf that was traditionally called the loup garou (pronounced rou garou). Admission is free, but all sales like rides and food benefit the Wetlands Discovery Center, a non-profit dedicated to studying the state’s coastal land loss crisis. One of the festival’s main highlights is its costume contest, which was ranked in the top 10 list of costume parties in the country by USA Today.

Blackpot Festival & Cookoff

Lafayette - October

Held in Lafayette’s living history museum, Vermillionville, Blackpot has amassed a cult following over the years that has turned it into one of the region’s liveliest festivals. The ticketed event includes live music on Friday night, which continues the next day along with a cookoff featuring an array of categories, like rice and gravy or gumbo. Many folks camp out on the museum grounds throughout the festival. The week before the festival, known as Blackpot Camp, features music and dance classes taught by the area’s experts.

Los Isleños Fiesta

St. Bernard - March

This festival celebrates Louisiana’s Isleños, a group of Canary Islanders who settled in the state in the late 18th century. Since these communities were isolated, many Isleños continued speaking Spanish well into the 20th century (although only a few speakers remain). Festival goers can sample Canarian dishes like ropa vieja paired with Canarian wine. Proceeds go to the Los Isleños Museum Complex in St. Bernard.

Tennessee Williams & New Orleans Literary Festival

New Orleans - March

This festival in March celebrates the literary scene of New Orleans, owing its name to Tennessee Williams who lived in the city at many periods throughout his life. The ticketed event based in the French Quarter features panels, book signings and talks from authors and poets.

Louisiana Book Festival

Baton Rouge - October

This festival brings together some of the best authors who call the Bayou State home. Held each year in October near the grounds of the Louisiana State Library, the free event hosts book signings, panels, workshops and events honoring talented Louisiana writers.

The Essential Mardi Gras Vocabulary of Carnival Season

Learn the varying lingo of Mardi Gras celebrations from New Orleans and the Louisiana countryside.

Learn the varying lingo of Mardi Gras celebrations from New Orleans and the Louisiana countryside.

Parades in New Orleans feature huge floats that host groups of people who toss beads, cups and other trinkets. Stock image/Pixabay

By Jonathan Olivier

Throughout the Mardi Gras season, there are a dizzying array of festivals, balls, and celebrations. It’s often a whirlwind of activity that culminates on Mardi Gras day before going dead quiet on Ash Wednesday, which marks the beginning of the fasting period of Lent. With so much history wrapped into one tradition, there’s a lot to learn. This list includes important Mardi Gras vocabulary that will help you navigate the many festivities during Carnival season.

The Catholic Roots of Mardi Gras

Much of the Mardi Gras vocabulary that exists today has roots in Medieval Catholic traditions. Stock image/Pixabay

Our modern Mardi Gras celebration is a vestige of many of medieval Europe’s Catholic traditions. Much of the Mardi Gras vocabulary that we have today stems from these ancient, storied rituals—even the name itself refers to Christian celebrations. Here are a few important terms that help contextualize important dates of Mardi Gras season.

Epiphany

This Christian feast is celebrated on January 6, commemorating three events: the baptism of Jesus Christ, the miracle at Cana, and the visit of the three Wise Men. This date is the official start of Mardi Gras season. In Louisiana, Kings’ Day and Twelfth Night are also terms used to refer to the Epiphany.

Lent

This is a 40-day fasting period where Catholics and some other Christians abstain from meat on Fridays and are encouraged to make other sacrifices (although in the past fasting was stricter). Adherents use this time to engage in self-reflection and repentance before the celebration of Easter. The first day of Lent is Ash Wednesday, a day of prayer where Catholics receive ashes on their forehead to symbolize death and repentance.

Carnival

The period from the Epiphany to the start of Lent marks Carnival season, more commonly referred to as Mardi Gras season. This period is a time of celebration and indulgence in preparation for the fasting and solemn reflection of Lent. In Louisiana, parades, courirs, balls, and other celebrations take place throughout the season–ramping up to a climax in the week before Mardi Gras day.

Boeuf Gras

Medieval celebrations called Boeuf Gras marked a feast of a fatted ox before Lent. The first carnival celebrations in North America were called Boeuf Gras and held in Mobile, Alabama. While a live bull was part of past Mardi Gras celebrations in New Orleans, today the boeuf makes an appearance as a paper figure.

Fat Tuesday

The English translation of Mardi Gras, this is the last day of Carnival season when people celebrate for the last time before the Lenten period of fasting.

King Cake

A circular cake made with Danish dough, cinnamon, icing, and sprinkles. A plastic baby that’s hidden inside represents Jesus. Typically, these coveted pastries are available from the Epiphany until Fat Tuesday.

New Orleans Mardi Gras Vocabulary

New Orleans parades are operated by krewes, such as the Krewe of Zulu, which is a majority-Black parading organization that dates back to 1916. Stock image/Pixabay

When Jean Baptiste le Moyne Sieur de Bienville landed near present-day New Orleans on March 3, 1699, he named the area la Pointe du Mardi Gras. While celebrations occurred in the area in the following decades, they really kicked off in earnest in the mid 19th century. These events are marked by ornate balls and parades that “roll” around the city throughout Carnival season.

Krewe

First used in 1857 by the Mistick Krewe of Comus, krewe refers to the groups of carnival organizations in New Orleans that organize and ride in parades.

Lundi Gras

Also known as “Fat Monday,” this term originally referred to the arrival of the king of the Rex Krewe by steamboat in New Orleans. In the 1980s, the term came to refer to its own slew of celebrations in the Crescent City.

Ball

Think of these as fancy galas hosted by Mardi Gras Krewes. Typically, there is a presentation of the Krewe’s royal court, which includes a king, queen, grand marshal, maids, and dukes.

Float

The Krewe’s procession of all of its court and other participants rides on floats, often elaborately decorated trailers pulled by vehicles, during a parade. Spectators stand nearby to catch an array of trinkets, called throws, which includes beads, doubloons, cups, and more.

Flambeaux

Before streetlights, torches lined the parade route so that the Krewe and spectators could see. These groups were often made up of enslaved Africans or free people of color who danced along with the parade. Today, groups of people still carry torches lit by kerosene.

Neutral Ground

This is the median between streets, often grassy and planted with trees, where spectators can watch a parade. This is to be differentiated from the “sidewalk side,” the other option for viewing parades. The term “neutral ground” originates from the median on Canal St, which divided the old French-speaking Creole city from the new English-speaking American city during the 19th century.

Mardi Gras Indians

These troupes of Black New Orleanians don elaborate costumes that are handmade throughout the year. They parade and dance on Mardi Gras Day in a Creole tradition commemorating the comradery of Africans and Native Americans in resisting racism. While Mardi Gras is an important day of celebration for Black Masking Indians, these practices continue yearlong, such as during “Super Sunday” in the spring.

Rex

Founded in 1872, Rex is one of the oldest krewes in the Crescent City. The krewe parades on Mardi Gras Day, and its king and queen are generally known as king and queen of Carnival.

Zulu

Founded in 1916, the Zulu Social Aid and Pleasure Club is the most prominent Black Mardi Gras organization and the only major majority-Black parading krewe. Zulu parades on Mardi Gras Day before Rex, and the kings of the two parades meet annually for a symbolic toast as part of the celebration.

Mardi Gras Vocabulary in Southwest Louisiana

Mardi Gras traditions in southwest Louisiana differ from their New Orleans counterparts. Ethan Castille/Télé-Louisiane

While Mardi Gras parades are common in southwest Louisiana, this region engages in its own variation of the tradition, called Courir de Mardi Gras. In several small towns around the Louisiana prairie, people dress up and roam the countryside, begging for gumbo ingredients from their neighbors. At the end of the day, revelers join together in town for a communal gumbo and music.

Capitaine

Courir de Mardi Gras participants take their orders from the capitaine who is the leader of the procession through the countryside. The only unmasked participant in the group, the capitaine is mounted on a horse and keeps order, and communicates with neighbors to gather gumbo ingredients.

Le Mardi Gras

The group of participants in the Courir de Mardi Gras is collectively referred to as the “mardi gras.”

Capuchon

The conical hat is the most recognizable part of the Courir de Mardi Gras costume. In medieval France, this tradition involved participants dressing up to mock the clergy and noble men and women. The capuchon is thought to have originated from revelers mocking the “hennin,” or tall hats worn by French noble women.

Courir

In French, courir means “to run.” Thus, the event itself is a Mardi Gras run. Throughout the day, the group of participants runs on foot or horseback through the countryside.

Chicken Chase

The mardi gras roams the countryside, visiting the houses of different neighbors in search of gumbo ingredients. While this can be rice or sausage, neighbors will often offer up a fowl of some sort, most commonly a chicken. The mardi gras then chases after the chicken. Some traditions, such as the Faquetaigue event in Eunice, features participants climbing a greased pole in order to reach a caged chicken sitting above.

A Guide to the Courir de Mardi Gras in Louisiana

Masked revelers roam the countryside, chase chickens, and sing and dance in this Mardi Gras tradition that has its roots in medieval France.

Masked revelers roam the countryside, chase chickens, and sing and dance in this Mardi Gras tradition that has its roots in medieval France.

Louisiana’s Courir de Mardi Gras has its roots in medieval Europe’s fête de la quémande, an ancient begging ritual. Ethan Castille/Télé-Louisiane

By Jonathan Olivier

As early as the 19th century, Mardi Gras took on two distinct forms in Louisiana. The most well-known is, of course, the New Orleans celebration that involves ornate balls, beads, and parades that were originally celebrated by the city’s Creole and Anglo-American elites. In south and southwest Louisiana, we find the other variant, the Courir de Mardi Gras that was popular among rural working-class families.

While traditions vary by town, generally a Courir de Mardi Gras involves costumed revelers roaming the countryside by foot, with others on horseback, as jesters and beggars. Traditional costumes include a tall, pointed hat called the capuchon, as well as a mask that completely covers the face, and a costume adorned with frilly fabric. The group–collectively referred to as the Mardi Gras–goes from house to house to beg for ingredients, often a chicken, from their neighbors to make a communal gumbo at the end of the day. At many events, there’s a common chant: Donnez quelque chose pour le mardi gras. This tradition has roots in the ancient begging rituals of medieval Europe’s fête de la quémande. Folklorist Carl Lindahl has called it “a tension of order and disorder” as roles are reversed—men dress as women, the young dress as the elderly—amid begging, flogging, inebriation, and general mischievousness. The revelers who are set loose on Louisiana’s prairies are reined in by the authority of le capitaine who oversees the event.

While the event is often depicted in national media as a grand party, Lindahl explained that these rural traditions have historically carried important implications for the community: it defined the boundaries of one’s community; it was a rite of passage for the traditionally all-male participants; it defined reliance on each other; and it also promoted the continuity of the group.

Tradition dictates that the procession of revelers, called the “mardi gras,” wear costumes, masks, and pointed hats called a capuchon. Ethan Castille/Télé-Louisiane

In the 20th century, World War II interrupted the celebrations and there was a decline in participation among many communities as many of the young men had been shipped overseas. Writing for 64 Parishes, Ryan Brasseaux noted, “When the war ended, many communities were slow to reinstitute local festivals. Community activists such as Paul Tate, however, worked to revive the tradition in Mamou and other communities.” At times, this revival incorporated women into what had been a tradition only reserved for men. Today, the spirit of the tradition continues in communities like Church Point, Eunice, and Mamou.

Each celebration has its own customs and rules—some runs allow only men and have strict costume rules, while others are co-ed or more lenient on garbs. This guide includes an overview of various Courir de Mardi Gras celebrations across south Louisiana.

Basile

The Basile Mardi Gras Association hosts a courir celebration at Lafayette’s Vermilionville the weekend before Fat Tuesday as a sort of demonstration. The main celebration is on Mardi Gras day, when men and women participate together. Basile’s Mardi Gras song is particularly unique and it’s sung various times throughout the day as the procession visits neighbors in the countryside.

Church Point

The Courir de Mardi Gras in Church Point adheres to tradition—only men are allowed to participate and they must don a mask and a costume. The event was revived in 1968, when it was established that it would be held on the Sunday before Mardi Gras day in order to not interfere with surrounding runs. Along with Mamou’s celebration, Church Point attracts thousands of people each year to witness the rituals, songs, and chicken chases that culminates with a procession through town and a communal gumbo.

Eunice

The Courir de Mardi Gras in this small town in St. Landry Parish started in the late 19th century and, like many in the area, it was revived after World War II. Although masks and costumes are required, the Eunice event allows for both men and women to participate—a few thousand people run each year. Eunice is home to the Cajun Mardi Gras Festival that takes place for five days, featuring music and a traditional boucherie on Lundi Gras.

The group of participants must follow the rules that are set by the capitaine, who functions as the leader of the event. Ethan Castille/Télé-Louisiane

Faquetaigue

In 2006, a group of friends founded a Courir de Mardi Gras that was more inclusive—meaning men and women could run together. Yet, they didn’t want to sacrifice tradition. Runners still don masks and costumes while roaming the backroads of the Faquetaigue community near Eunice. In addition to a horse-mounted capitaine and roaming villains, revelers attempt to reach a chicken that’s housed in a cage atop a greased pole. At the end of the day, participants enjoy gumbo, boudin, and live music.

L’Anse/Mermentau Cove

Hosted by Cadien Toujours, this run typically takes place more than a week before many other Mardi Gras celebrations. In accordance with local tradition, only men who are wearing a mask and costume are allowed to participate. The group travels through the countryside of Mermentau Cove, chasing chickens and greased pigs, before ending in a celebration full of dancing and traditional Louisiana fare.

LeJeune Cove

In 2002, masked and costumed men got on their horses or roamed around on foot, chanting the Lejeune Cove Mardi Gras song for the first time in nearly 50 years. On the Saturday before Mardi Gras, this run features a traditional chicken chase, costumes, and Cajun music.

A chicken chase stems from the tradition of begging for ingredients from neighbors to feed the community. In Louisiana, this communal meal was always gumbo. Ethan Castille/Télé-Louisiane

Mamou

The Courir de Mardi Gras in Mamou is one of the biggest celebrations of its kind in Louisiana, after its revival in the 1960s. This traditional run allows only men who are fully costumed and masked. Many participants ride horses on this run, while others opt to get ferried by a trailer in the rear of the group. The procession ends on 6th Street in town for a final fais do do and gumbo before the beginning of Lent.

Soileau

Traditions in this Allen Parish community have deep roots in Louisiana’s Black Creole culture. In the 19th century, the Courir de Mardi Gras was held in L’Anse de ‘Prien Noir. Today, both men and women take part to chase chickens and beg for gumbo ingredients from their neighbors.

Tee Mamou-Iota

This tradition in Tee Mamou/Iota features an all-women run the Saturday before Mardi Gras day, when the all-men run takes place. Both events require traditional costumes for a day filled with chicken chases and dancing. On Mardi Gras day, the men’s run ends with a parade at the Folklife Festival in town.

12 Bakeries That Make the Best King Cake in Louisiana

A guide to the bakeries across the Bayou State that produce some of the best king cakes during Mardi Gras.

A guide to the bakeries across the Bayou State that produce some of the best king cakes during Mardi Gras.

King cakes have existed in Louisiana since at least the 19th century. Jonathan Olivier/Télé-Louisiane

By Jonathan Olivier

It’s that coveted time of year when bakeries across Louisiana begin churning out king cakes for just a few short weeks during carnival season. While these colorful pastries are ubiquitous, they vary in quality or taste by bakery and by city. This guide rounds up the bakeries that make the best king cakes across the Bayou State—from the Crescent City to Acadiana to the hills of north Louisiana.

New Orleans Metro Area

New Orleans offers a dizzying array of options for those looking for a king cake during Mardi Gras. Lilah’s Bakery

Caluda’s King Cakes

Harahan

Caluda’s King Cakes has been producing some of the best king cakes in the New Orleans metro area for 35 years. Started by John Caluda and now run by his son, Josh, this bakery has taken home numerous awards, most recently the 2022 King of Cake award that tallied more than 42,000 total votes. Caluda’s uses a moist Danish dough topped with cinnamon sugar and melted butter. Vanilla icing is made fresh in house. A local favorite is their praline, made even richer with the option of a cream cheese filling.

Manny Randazzo’s King Cakes

Metairie

Due to the popularity of their king cakes, in 1995 Manny Randazzo devoted the business to making the seasonal treats each year starting in December. Options include traditional cinnamon versions with the trademark Randazzo white icing, as well as the pecan praline, apple, strawberry, and lemon-filled varieties. Lines can often stretch outside the doors during the peak of Mardi Gras season, but it’s well worth the wait.

Antoine’s Famous Cakes & Pastries

Gretna

Antoine’s king cakes don’t feature granulated sugar, but thick, white icing along with green, purple, and gold icing drizzled on top. Antoine’s is home to the original queen cake, which features five different fillings like blueberry and strawberry. While the Gretna location is the original, another location in Metairie opened several years ago.

Haydel’s Bakery

New Orleans

A Crescent City institution for decades, Haydel’s Bakery features all of the traditional options plus creations like German chocolate and brownie chocolate chip. If you find yourself in another state this season, Haydel’s can quell homesickness with shipping options. Their “Da Parish” package features a traditional king cake, a history of carnival season pamphlet, a pack of French Market coffee, and a pack of beads.

Berry Town Produce

Hammond

Hundreds of king cakes sell each day at this favorite on the North Shore, along with another location in nearbyPonchatoula. Cindy Henderson is Berry Town’s owner, and her family owns a sizable strawberry farm in a region dubbed the strawberry capital of Louisiana. This is the inspiration for Berry Town’s signature and amazingly fresh strawberry cream cheese king cake.

South Louisiana

The home of numerous courir de mardi gras celebrations, south Louisiana has its own unique carnival season traditions—and a wide selection of king cakes. Jonathan Olivier/Télé-Louisiane

Ambrosia Bakery

Baton Rouge

Founded by New Orleans natives Cheryl and Felix Sherman in 1993, Ambrosia Bakery has grown to be a favorite of the Capital City, selling more than 20,000 king cakes each year. While traditional options abound, Ambrosia’s Zulu king cake is a sensation all its own. It features a coconut spread on the inside with chocolate chips and cream cheese, topped with chocolate icing and toasted coconut.

Keller’s Bakery

Lafayette

For people in Acadiana, Keller’s and king cake are synonymous. The Keller’s secret lies in a Danish pastry recipe that’s more than 120 years old—the Keller family were bakers in France before coming to south Louisiana. Their king cakes are stuffed with fresh filling and topped with light frosting and sprinkles. Ordering ahead is recommended during the height of Mardi Gras season.

Cannata’s Market

Houma

Cannata’s has long been a favorite for communities down the bayou in Terrebonne and Lafourche parishes, but the rest of the state is catching on. This Houma bakery was a “people’s choice” winner at the 2017 and 2019 King Cake Festival. Part of the secret to success has been the bakery’s “gooey butter,” featured in options like the rougagooey king cake and the gooey butter snikerdoodle.

Misse’s Grocery

Sulphur

The bakery of this small-town grocery store in the Lake Charles area churns out some of the best king cakes in southwest Louisiana. Local favorites include the peanut butter cup, featuring a peanut butter cream filling and chocolate icing, as well as the cookies ‘n’ cream, topped with cookies and filled with cream cheese.

North Louisiana

Although miles from the heart of Mardi Gras celebrations in New Orleans, north Louisiana bakeries have proven their king cakes can compete with the best of them. Jonathan Olivier/Télé-Louisiane

Atwood’s Bakery

Alexandria

Atwood’s has been serving up quality baked goods for central Louisiana since 1977. Owner Mark Atwood stuffs his king cakes so full that there isn’t a hole in the middle. The cream cheese option, for example, is packed with more than a pound of filling.

Lilah’s Bakery

Shreveport

Lilah’s Bakery makes some of the best king cakes in all of north Louisiana. The most popular option is the cinnamon ‘n’ cream cheese, featured alongside those like red velvet, cookie butter, and banana split. Another must-try is the tiramisu king cake, made with brioche dough, stuffed with cream cheese, cocoa and espresso powder, and topped with more cocoa powder and an espresso buttercream.

Daily Harvest Deli & Bakery

Monroe

Freshness sets apart this bakery from the rest. Their king cakes are made with flour that has been freshly ground in-house. Find options like praline, lemon curd, banana cream, blueberry and more.