New Speakers of French in Louisiana: Continuing a Legacy

In Lafayette, former immersion students are establishing the institutions necessary to support a new generation of francophones.

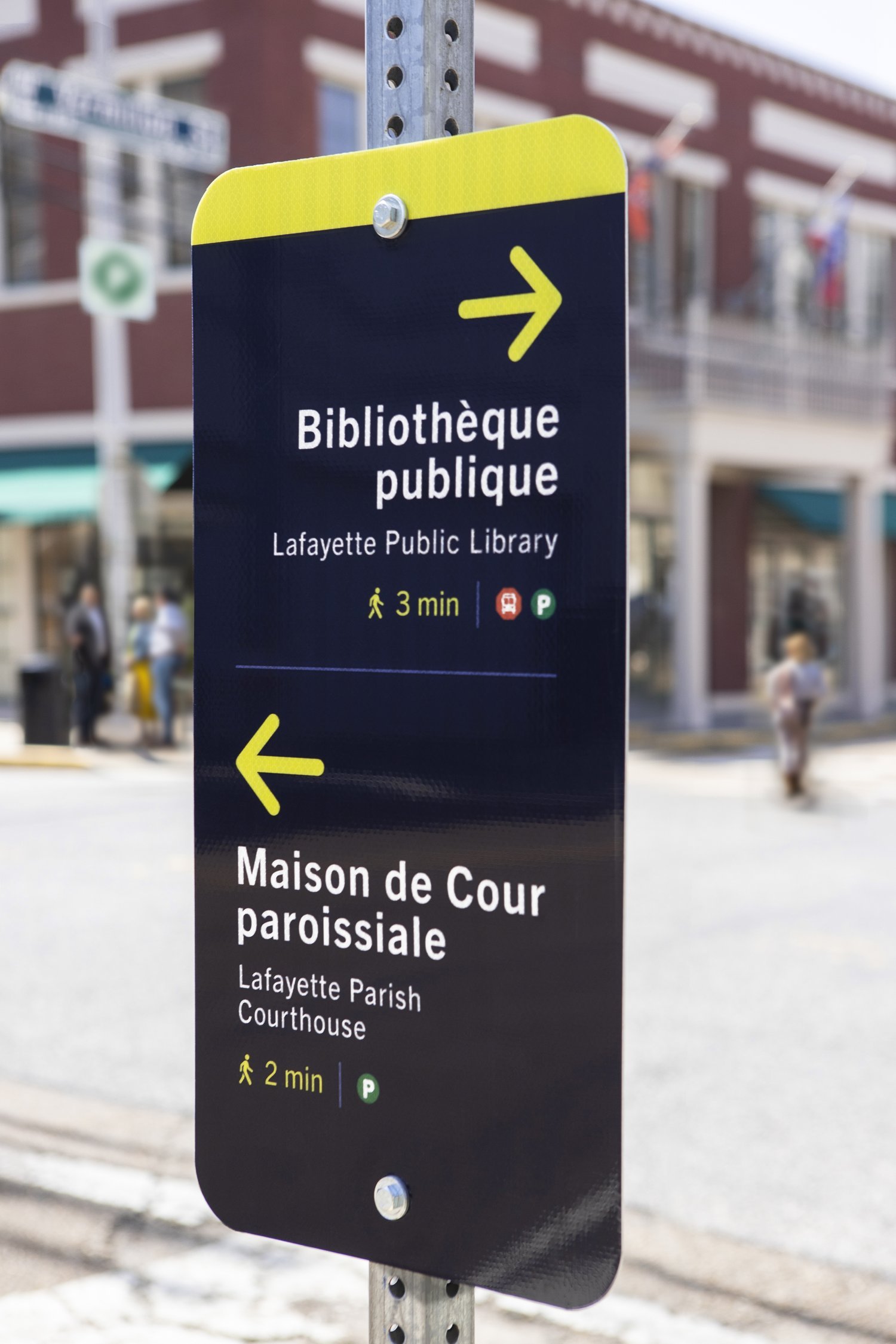

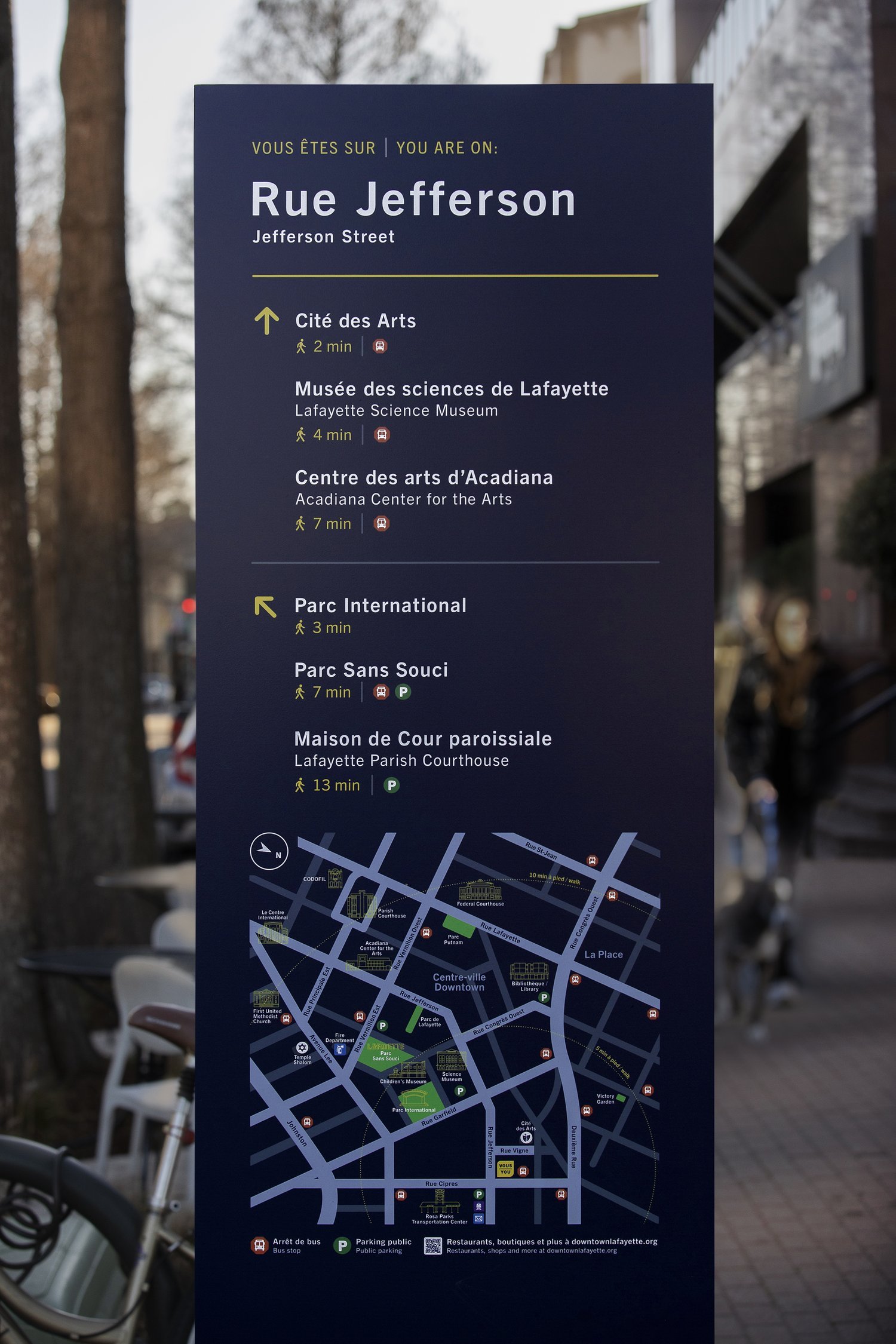

In 2021, Stephen Ortego worked with Makemade and Lafayette Consolidated Government to design and implement bilingual signs in downtown Lafayette. Jonathan Olivier/Télé-Louisiane

This article is Part 2 in a series on French in Louisiana. Part 1, which explains the complexities of French immersion in Louisiana, is available here.

By Jonathan Olivier

Renée Reed began learning French when she was around five years old at Evangeline Elementary School, an immersion program in Lafayette. Although she left the program just a year later, French remained in her life through learning Cajun music and spending time with her grandparents who are native speakers of Louisiana French.

“I remember a period in my life when I was little, speaking mostly French at school,” she said. “And then when I’d go to my grandparents, because I’d go to my grandparents a lot, we would speak French.”

Despite Reed’s familial link to French, English was still her mother tongue. Given that English had become the region’s dominant language for a few decades by the time she was growing up in the early 2000s, it was easy for French to take a background role. Then, in high school, she began playing Cajun music with her mom, Lisa Trahan, who plays with the Magnolia Sisters, and her dad, Mitchell Reed, who played with BeauSoleil. Later on, as a student at the University of Louisiana at Lafayette, she majored in French and music.

Due to the various ways Reed had learned the language, she had created a patchwork of French competencies. In order to form a more solid base, in 2019 when she was 20, she participated in a five-week immersion program at the Université Sainte-Anne in Nova Scotia, Canada. Participants could only speak French for the duration of the program, during classes and a variety of workshops, games and extracurricular activities.

“That's where you're really learning is when you're in real life with the language,” said Reed, now 24. “And I had never been in those kinds of situations before. And so, in that experience, I was learning more than I was even processing. By two weeks in, I could really talk and I wasn't even aware of how much I was learning.”

Renée Reed plays with several Cajun music groups in Lafayette, as well as a solo act that allows her to write music in French. Courtesy of Renée Reed.

Reed is what linguists in Europe who study minority and heritage language revitalization call a “new speaker.” Typically, this refers to someone who has had little home or community exposure to a heritage language, and who then acquires it via immersion education or language revitalization projects.

In the last few decades, French has been principally passed down to younger generations of Louisianans like it was for Reed—through immersion education as children or adults. Many native speakers of Louisiana French are often elderly, usually older than 60, yet many more are in their 70’s or 80’s. As this demographic continues to age, in the near future new speakers of French in Louisiana will comprise the bulk of the francophones in the state.

This generation of new speakers, often younger than 40, represents a generational shift that developed after home transmission of French faded in the mid to late 20th century. Their grandparents likely spoke French as a first language, and their parents are likely anglophones with some knowledge of French. This contact with native speakers of Louisiana French, although often limited, gives new speakers the ability to grasp what they can and pass it on, according to Stephen Ortego, a Lafayette-based architect who, as a teenager, also studied at Université Sainte-Anne.

“Our generation is a sort of bridge between our grandparents who almost all spoke French and the next generation,” said Ortego, 39, from Carencro. “It’s up to us to transfer the language to this next generation. And it’s important to have a certain percentage of us who continue what makes us special.”

In order for French to continue to remain viable with this new generation, folklorist and professor emeritus at the University of Louisiana at Lafayette Barry Ancelet wrote in a 1988 essay that there must be the development of a “French environment.” This includes a society where French is institutionalized and visible alongside English, including the existence of radio and television programs, magazines, books, billboards and road signs. “If someone is to bother learning French,” Ancelet wrote, “there must be something worth doing, reading, seeing, and hearing in the language.”

For much of the decades following Ancelet’s call to restore French in the state, his francophone environment failed to gain steam. Yet, in the last few years, there has been a flurry of progress thanks, in large part, to former French immersion students. Scattered about south Louisiana are signs of new life that is nurturing French within the state’s wider society through infrastructure, music and art.

Building a French Environment

Ortego heard French often when he was a kid, spending time in Washington or Opelousas with his French-speaking grandparents, neighbors and extended family. But he wasn’t immersed in a society where French is institutionalized until, at age 19, he attended Université Sainte-Anne’s immersion program. It was there that he began dreaming in French, thinking in French, all without effort. This, Ortego said, provided him with a solid base of the language so that he could return to Louisiana with the linguistic skills to live in French.

“Afterwards, I continued to speak in French with my grandparents, neighbors and friends,” he said. “I made friends my age who were in immersion. I refused to speak in English with people in Louisiana who I knew spoke French because I wanted to learn. It was the only way to learn.”

Only a few years later, Ortego served as a state representative, from 2012 to 2016. During that time, he invested in institutionalizing French in Louisiana. Ortego’s House Bill No. 998 in 2014 allowed parish governing bodies, either police juries or parish councils, to ask the Louisiana Department of Transportation and Development (DOTD) to provide bilingual signs along state and federal highways. The bill was ultimately signed into law by Governor Bobby Jindal, becoming Act 263, which first tasked DOTD with adopting changes to the Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices (MUTCD) to include bilingual signage.

Bilingual signs were installed in Lafayette in 2021 thanks to Makemade, SO Studio Architecture and Lafayette Consolidated Government. Photos of signs courtesy of Makemade.

“We had already started talking with several parish presidents or presidents of the police jury in the 22 parishes of Acadiana,” Ortego said. “We had the intention that as soon as the policy was adopted by DOTD, we wanted to go to each parish and talk with the police juries or the parish councils.”

According to Ortego, DOTD never took steps to adopt the changes to the MUTCD. So, nearly 10 years later, local parishes still don’t have the opportunity to adopt bilingual signs. Yet, Ortego made progress on this front in 2021. His firm SO Studio Architecture was able to work with Makemade and Lafayette Consolidated Government to install bilingual wayfinding and street signs throughout downtown, called the Route Lafayette project.

While these signs exist only around downtown Lafayette at the moment, Ortego’s firm and Makemade also took some of the steps that DOTD has not, making changes to the MUTCD that features bilingual signs that go beyond wayfinding, such as stop signs. If the parish government would decide to adopt these changes parish-wide, Ortego said the document outlining changes to the MUTCD would provide a pathway to do so. On the state level, Ortego emphasized that, legislatively, everything is in place for DOTD to expand bilingual signage.

“Maybe there are people who can ask their state representatives to return to this question and push more to maybe provide money to DOTD to adopt the policy that is already written in law,” Ortego said. “So, if it’s financed, there aren’t any more excuses.”

A Bridge to the Next Generation

Philippe Billeaudeaux was part of the first French immersion class in Lafayette in the early ‘90s at S.J. Montgomery Elementary School, which is now housed at Myrtle Place Elementary. Billeaudeaux continued on to Prairie Elementary School and then Paul Breaux Middle School, while he also heard some French at home from his father.

“I have continued using French in my creative projects,” said Billeaudeaux, 37, from Lafayette. “I play Cajun and Creole music with Feufollet, Steve Riley and Cedric Watson. I also do a cartoon in Louisiana French with filmmaker Marshall Woodworth, who lives in New Orleans. We created ‘Les Aventures de Boudini et Ses Amis,’ a cartoon for immersion students.”

Boudini, a project between Billeaudeaux and Woodworth’s Creole Cartoon Company and Télé-Louisiane, first aired online in January 2021. This year, a new season of the series will air on Louisiana Public Broadcasting. With characters voiced by Louisianans like long-time immersion teacher and poet laureate of French Louisiana, Kirby Jambon, and musicians Cedric Watson and Louis Michot, immersion students have the opportunity to hear Louisiana French from within the local francophone community.

Philipe Billeaudeaux (left) and Marshall Woodworth created the cartoon “Les Aventures de Boudini et Ses Amis,” which provides immersion students a way to learn Louisiana French. Courtesy of Philippe Billeaudeaux

In the last few years, there has been an uptick in projects led by former immersion students. In 2018, a podcast called “Charrer-Veiller,” was founded by Joseph Pons and Chase Cormier; Drake LeBlanc, the chief creative officer and co-founder of Télé-Louisiane, and Jo Vidrine, a staff photographer, participated in Lafayette’s immersion schools; and “Le Bourdon de la Louisiane,” an online news journal, was founded in 2018 by former Sainte-Anne student Sydney-Angelle Dupléchin Boudreaux and also Bennett Boyd Anderson III.

Around Lafayette, a few organizations target immersion students in order to provide examples of French existing outside the classroom. At Vermilionville, Lafayette’s living history museum, the staff is again hosting a summer camp in July for French immersion students. Zach Fuselier, a former immersion student, works at Vermilionville as the heritage gardener where he tends to the museum’s animals and garden, offering presentations virtually every day in French.

“Often, we have tourists from Canada and France and other French-speaking countries,” said Fuselier, 26, from Lafayette. “So, I can share my culture with them and I can do it in French. It’s a language that they’re most comfortable in. And I can show them that there are still people who speak French in Louisiana.”

Despite the recent projects of some former immersion students, Fuselier said that the majority of his former classmates likely don’t use the language in their everyday life. Life outside of school often exists solely in English—even for him, English is the language he uses the most in his life. That’s why it’s even more important, he said, to nurture a francophone environment so that immersion students, both current and former, continue to exist in the language after they leave the classroom.

“We’ve got to provide an incentive for children, first to learn the language and second to use it in their everyday life,” he said. “If we want to bring back French, we have to have more resources, just to live in French.”