Developing New Francophones With French Immersion Schools

More than 5,000 children are learning French through immersion in Louisiana, establishing a small but growing population of new francophones across the state.

This article is Part 1 in a series on French in Louisiana. Part 2, which explores how former immersion students are using their language skills to support French in the state, will be published on May 9.

Story by Jonathan Olivier | Photos by Jo Vidrine

In the middle part of the 20th century, home transmission of French began to rapidly decline in Louisiana—what linguists call a “language shift,” as English became the dominant language spoken at home and throughout the state’s communities.

According to 1990 census data, more than 80 percent of self-identified Cajuns born at the turn of the 20th century still spoke French as their first language at home, according to Shane K. Bernard in his book “The Cajuns: Americanization of a People.” That figure fell to 21 percent for those born between 1956 and 1960, and even lower to eight percent for those born between ‘71 and ‘75. “A similarly dismal number spoke French as a second language,” Bernard wrote. While this doesn’t represent all francophone groups in Louisiana, it does offer an idea of the extent of the language shift that occurred in the 20th century.

This trend continued for decades so that, these days, French has essentially disappeared as a first language learned at home or spoken at large throughout communities. Instead, French is now typically learned by monolingual anglophone children as a second language in French immersion schools, where they learn an academic, standard variant of the language. Therefore, immersion has become one of the most important and viable ways to grow a population of new francophones in Louisiana.

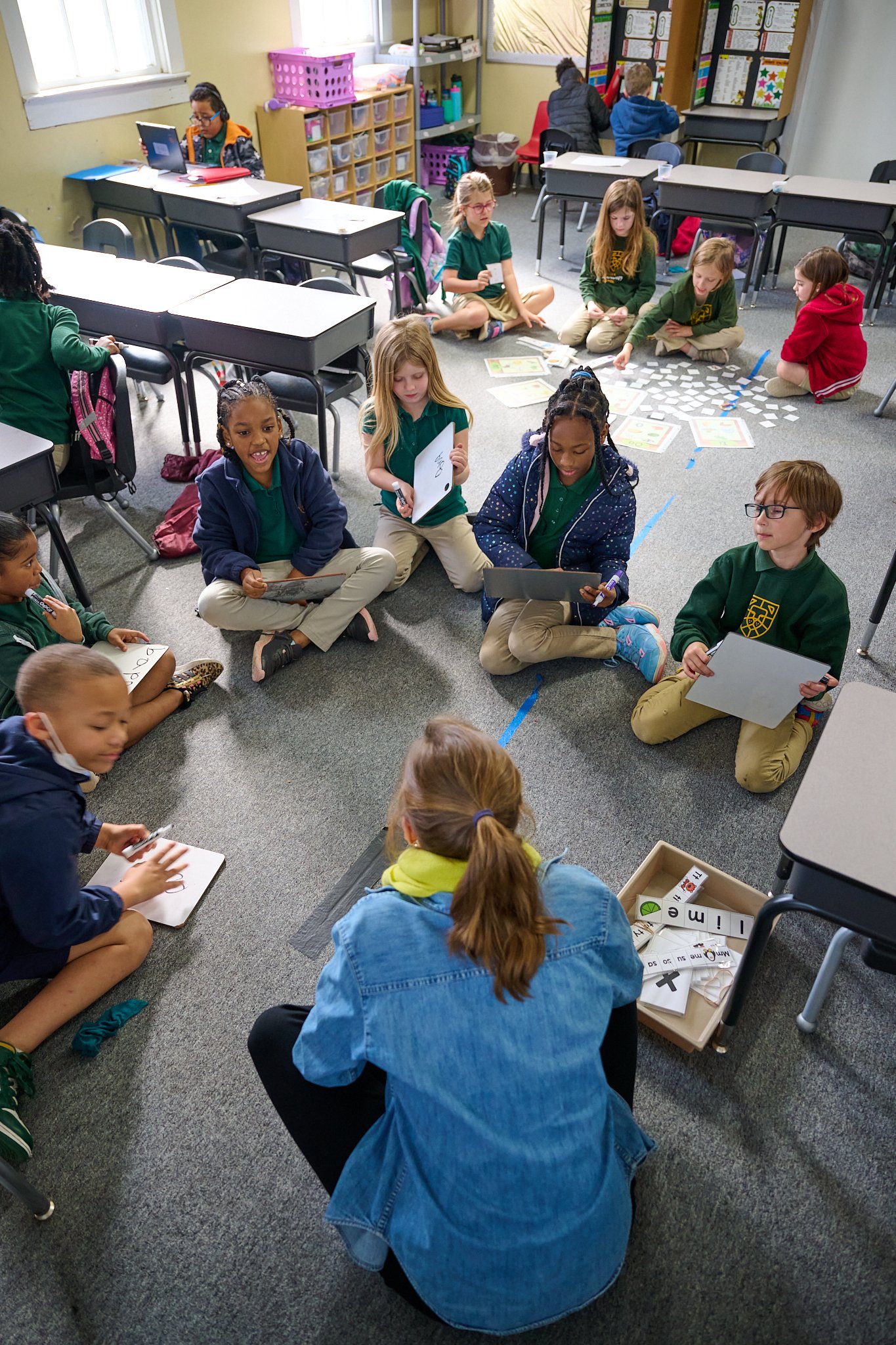

“We have kindergartners who are speaking full sentences to us in French by Christmas, telling us what they need,” said Lindsay Smythe, school leader at École Saint-Landry, an immersion charter school in Sunset. “And they can remain and participate in French all day long.”

At École Saint-Landry, children who are typically monolingual anglophones begin in kindergarten where they spend the majority of their day learning in French through courses like math and science. Usually, they are only taught in English during English Language Arts classes.

Founded in 2021 as a full immersion campus with kindergarten and first grade, École Saint-Landry currently houses kindergarten through second grade. Smythe said they’ll continue adding grades as their current group of students progresses each year, eventually offering up to the eighth grade.

In 2010, immersion students totaled 3,416 statewide. Today, the 103 students currently enrolled at École Saint-Landry are among more than 5,100 children who participate in French immersion at more than 35 schools across the state. They have joined the thousands more who have participated in immersion over the last three decades. Several thousand more have participated in immersion programs as adults, most notably at the University Sainte Anne in Nova Scotia, one of the Acadian provinces of Canada.

Yet, immersion is still a niche effort that exists within a wider anglophone education system. Immersion students make up less than one percent of Louisiana’s school-age demographic—there are around 1 million children under 18 in the state. So, growing the number of schools that offer a program has been a priority of language activists and educators for years now.

According to Michèle Braud, world languages specialist at the Louisiana Department of Education, state officials involved with immersion would like to continue expanding enrollment by five percent each year. Although Braud’s department is still compiling numbers from the 2022-2023 academic year, she said enrollment is up.

In August 2023, three more programs will open: École Pointe-au-Chien in Pointe-aux-Chênes will become the first program serving a predominantly Indian French population; Evangeline Reimagine Academy will open in Ville Platte thanks to Louisiana’s Reimagine School Systems Grant; and Fairfield Elementary Magnet School will be the first program in Shreveport.

The Beginning of French Immersion Schools in Louisiana

James Domengeaux, who in 1968 was pivotal to the establishment of the Council for the Development of French in Louisiana (CODOFIL), often said that “L’école a détruit le français; l’école doit le restaurer.” “School destroyed French; school must rebuild it.” Of course, what Domengeaux was referring to is that French in Louisiana experienced such a rapid decline in the 20th century, in part, due to the 1921 state constitution that made English the official language of the classroom. This resulted in French being barred from schools—corporal punishment was often inflicted on children who spoke the only language they knew in order to force them to learn English.

Domengeaux’s vision was to reestablish the language throughout Louisiana’s communities via education. In the 1970s, CODOFIL initially instituted this plan through French language classes for short durations during the school day—the results proved to be unpromising. Domengeaux then looked to Canada, and he learned of experimental yet successful French immersion schools that, instead of teaching students French as a language class, taught them most classes in the language itself. Domengeaux’s interest led to a pilot immersion program in Baton Rouge in 1981. Yet, the programs didn’t really begin to take off until the ‘90s.

In the early 2010’s, CODOFIL’s mission was amended through a series of laws. In 2010, former Senator Eric Lafleur, D-Ville Platte, introduced Act 679, which passed to redefine CODOFIL’s purpose. The agency was specifically tasked with enhancing Louisiana’s French immersion schools in coordination with the Louisiana Department of Education and the Louisiana State Board of Elementary and Secondary Education through the International Associate Teacher Program.

Establishing an immersion program in a Louisiana school district is possible thanks to legislation passed in 2013. Act 361, called the “Immersion School Choice Act,” states that parents or legal guardians of at least 25 pre-school aged children who live in a particular school district need to sign a petition, and state law dictates a school board must create an immersion program. Unfortunately, the law has no enforcement mechanism, and at least four petitions have gone unanswered by local school boards: two in St. Tammany Parish and two Terrebonne Parish. Braud with the LDOE said that the more successful tract to opening a program is for parents to simply begin a conversation with the school district, CODOFIL and LDOE.

Typically, a program is housed within a traditional, English-language school that offers a French immersion tract. Some schools only offer French immersion, such as École Saint-Landry. There are only a handful of options for high schoolers who want to continue in immersion, such as Lycée Français in New Orleans and Lafayette High in Lafayette.

French in an Anglophone Curriculum

Rebuilding French after several generations of language shift hasn’t been an easy task. The lack of home transmission means that Louisiana doesn’t have an adequate pool of francophone educators who are certified. So, CODOFIL and its partner agencies coordinate with foreign governments to provide U.S. Department of State’s J-1 visas to teachers who instruct in Louisiana for a three-year period, which can be extended for two more years. The state has formal agreements for teacher exchanges with France, Canada, and Belgium, and teachers also come from other countries too, increasingly from Francophone Africa.

The reliance of foreign teachers means that students often don’t hear Louisiana French in the classroom, as educators are unaware of its regional variances. The state’s Minimum Foundation Program (MFP) also caps the number of foreign teachers that can instruct in immersion in Louisiana at 300. Therefore, priority is given to elementary programs. The MFP cap, plus high rates of attrition among immersion students post middle school, have led to the creation of only a handful of high school immersion programs.

In order to expand her burgeoning school, Smythe with École Saint-Landry would like to see the state law changed to remove the MFP cap. Because, as of now, expanding her school beyond eighth grade would be a challenge—she’d have to find local teachers who are francophone and certified to teach, which she said can be difficult in small towns like hers.

Foreign teachers are also tasked with navigating Louisiana’s curriculum standards. Each school is subject to its local school district’s curriculum, which is often written in English. “So, if a parish adopts a math curriculum, if that math curriculum does not exist in French, it is on the shoulders of the immersion teachers to translate the entire curriculum into French,” Smythe said.

Smythe said she’d like to see the creation of a state-wide French language arts curriculum that could be applied to all of the French immersion schools. However, some schools, such as Audubon Charter School in New Orleans, follow both Louisiana and French national academic standards, the latter set forth by the French Ministry of Education that is part of Agency for French Teaching Abroad (AEFE).

According to Sophie Capmartin, French program director at Audubon, her students learn using books and materials purchased from France. “The work on a French curriculum allows a greater openness to the world and brings an intercultural perspective on certain themes or in the way of approaching certain disciplines,” Capmartin said. “The texts in French literature are integral works of French-speaking authors that students study as soon as the third grade.”

Capmartin noted that students at Audubon typically score above or on the French national average on the French national exam, which certifies someone’s French language abilities. In general, immersion students tend to perform better on standardized tests than their monolingual peers.

Despite the challenges of reestablishing French within an anglophone educational system, Smythe said she recognizes the many benefits her students are receiving. Plus, she feels she is doing her part in reconnecting her students to a unique linguistic heritage.

“As a French speaking society, I personally feel very honored to be a part of what we’re doing,” Smythe said. “Anybody who is bilingual, they're just going to have more opportunities, they're going to have more doors open. I'm just so pleased that we were able to bring this to our students, because they didn't have that opportunity before, and now they do.”