Dunn: Job Creation is Essential to the Louisiana Francophone Movement

State laws already exist that would highlight and strengthen francophone businesses in Louisiana. The next step is to fund and staff them.

State laws already exist that would highlight and strengthen francophone businesses in Louisiana. The next step is to fund and staff them.

Taalib Auguste (right), who speaks English, French, and Louisiana Creole, is a member of a multilingual staff who leads tours at Laura Plantation in Vacherie. Taalib Auguste

By Joseph Dunn

Joseph Dunn served as the executive director of the Council for the Development of French in Louisiana (CODOFIL). He is the director of PR and marketing for Laura Plantation in Vacherie, Louisiana.

At Laura Plantation in Vacherie, Louisiana, tourists from France, Québec and Belgium wait in the gift shop for the 1 p.m. French tour to begin. The historic Creole sugar plantation offers tours en français three times a day:one in the morning and two in the afternoon. When asked if the tour option in the French language influenced his decision to visit, Guillaume, from France, replied, “It’s important to have a tour in French to understand this history. We have this fantasy in France about Louisiana. The way it is presented in ads and on television makes us believe that we will hear at least some people speaking French, but we’ve been here for three days and this is the first place we have spoken French with locals since our arrival.”

Guillaume’s experience is not an exception. It’s the norm for Francophone tourists visiting the state. Géraldine, from Québec, was also recently in Louisiana. Visiting world-renowned museums in New Orleans, she was astonished at the absence of language options. The interpretative panels and digital kiosks are only in English. “Being from Québec, I automatically look for the button that will allow me to view information in French. I’m really surprised that museums in a city with such deep French history don’t take into consideration that not all of their visitors speak or read English.”

Dial 8 for French

Thanks to an automated answering service in Ottawa, Canada’s Lord Elgin Hotel is just one of many businesses that provides the option “composez le 8 pour continuer en français.” In the capital city of a nation where English and French are official languages, it is expected that services, especially in the public and other essential sectors, be equally available in French as in English.

Such a scenario could exist in Louisiana thanks to legislation passed more than a decade ago. In 2010, Act 679 of the Louisiana legislature recreated the Council for the Development of French in Louisiana (CODOFIL), giving the agency specific mandates to oversee the state’s economic development and tourism promotion initiatives in French, as well as to create a certification system to identify festivals, businesses, and other entities that provide services in French. (See CODOFIL’s “Oui!” Initiative).

Act 106, also passed in 2010 and called “The Louisiana French Language Services Program,” mandates that CODOFIL and the Louisiana Department of Recreation, Culture, and Tourism (DCRT) to create a census of each French-speaking state employee in order to :

to the extent practicable, to provide state government services to French- speaking citizens and visitors in the French language

to assist Louisiana citizens who speak French in dealing with and receiving services from the state government so as to support the long-term sustainability of Louisiana's historic French cultural heritage

to assist French-speaking visitors to the state and thus to promote an increase in tourism and greater investment in the state from Francophone countries

The law, modeled after French-language services legislation in Nova Scotia, Canada, also requires the department to “provide for appropriate insignia, such as a badge with the word "Bienvenue" or "Bonjour" to identify employees who will assist French-speaking clients in accessing and using department services.”

Despite this legislation, these important mandates are largely unknown to the Louisiana public and they remain unfunded and thus unstaffed.

It is curious, especially given the popularity of French immersion schools and the publicity they garner from local and international media, that no real pathways have been created to make French “useful” in the Louisiana tourism marketplace or in other professional sectors. This could easily be remedied by the introduction of policies in state and local governments (especially tourism promotion offices) which require the active recruitment and hiring of French speakers from Louisiana.

Jobs in French Equal Economic Development

At Laura Plantation, the site employs two full-time and eight part-time bilingual staff members who ensure the operation of the site, handle social media and public relations, conduct archival research, greet guests, lead tours, and sell merchandise… all in French. These efforts at hiring and training French-speaking staff members, especially young Louisianians eager to use their language skills in a professional setting, along with cultivating the Francophone tourism market, have been fruitful. Francophone visitors accounted for 20 percent of annual visitation in 2022.

French is a natural resource in Louisiana that we simply need to cultivate and develop. At Laura, we offer tours in French and people come for that. It’s not really rocket science.

New Speakers of French in Louisiana: Continuing a Legacy

In Lafayette, former immersion students are establishing the institutions necessary to support a new generation of francophones.

In Lafayette, former immersion students are establishing the institutions necessary to support a new generation of francophones.

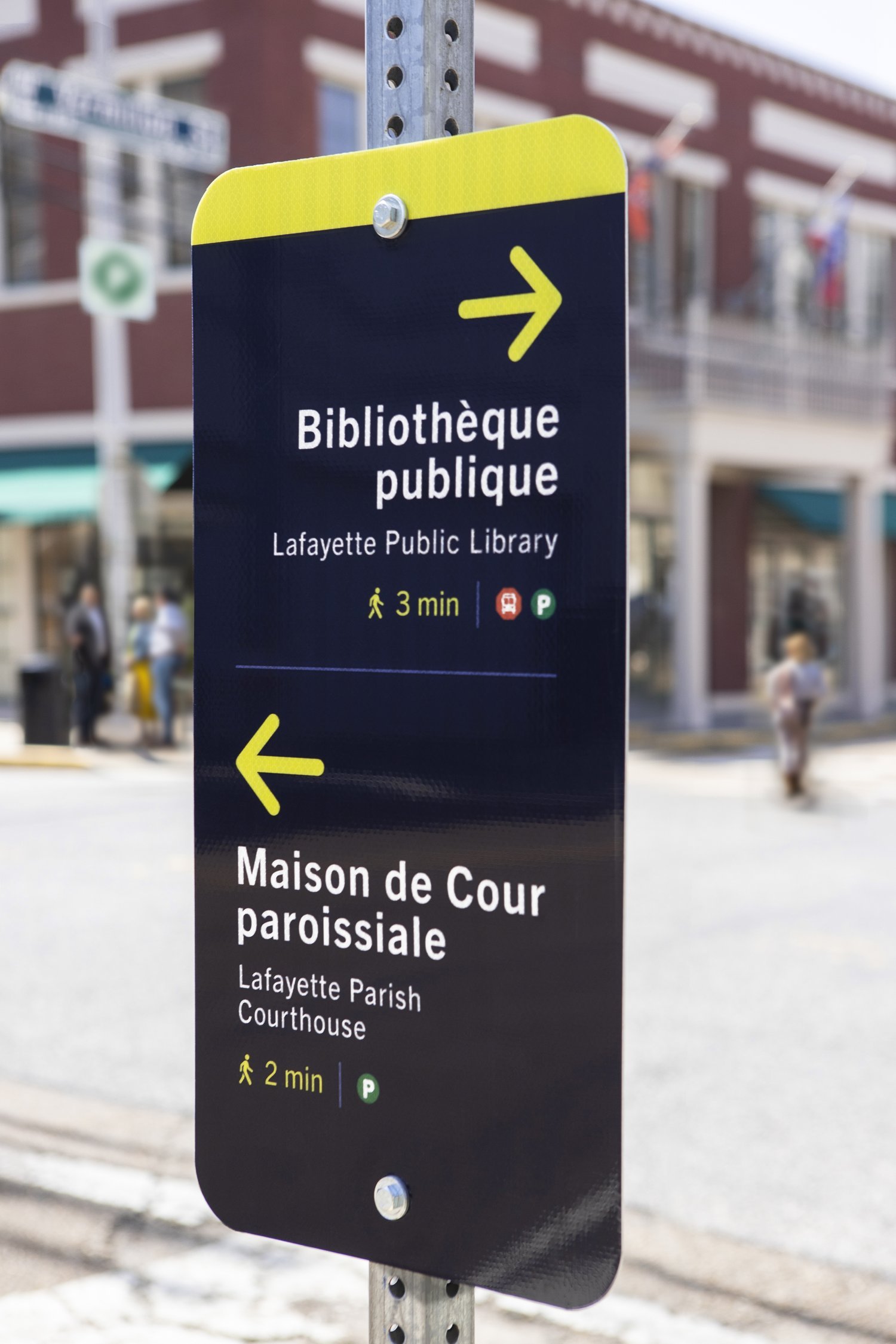

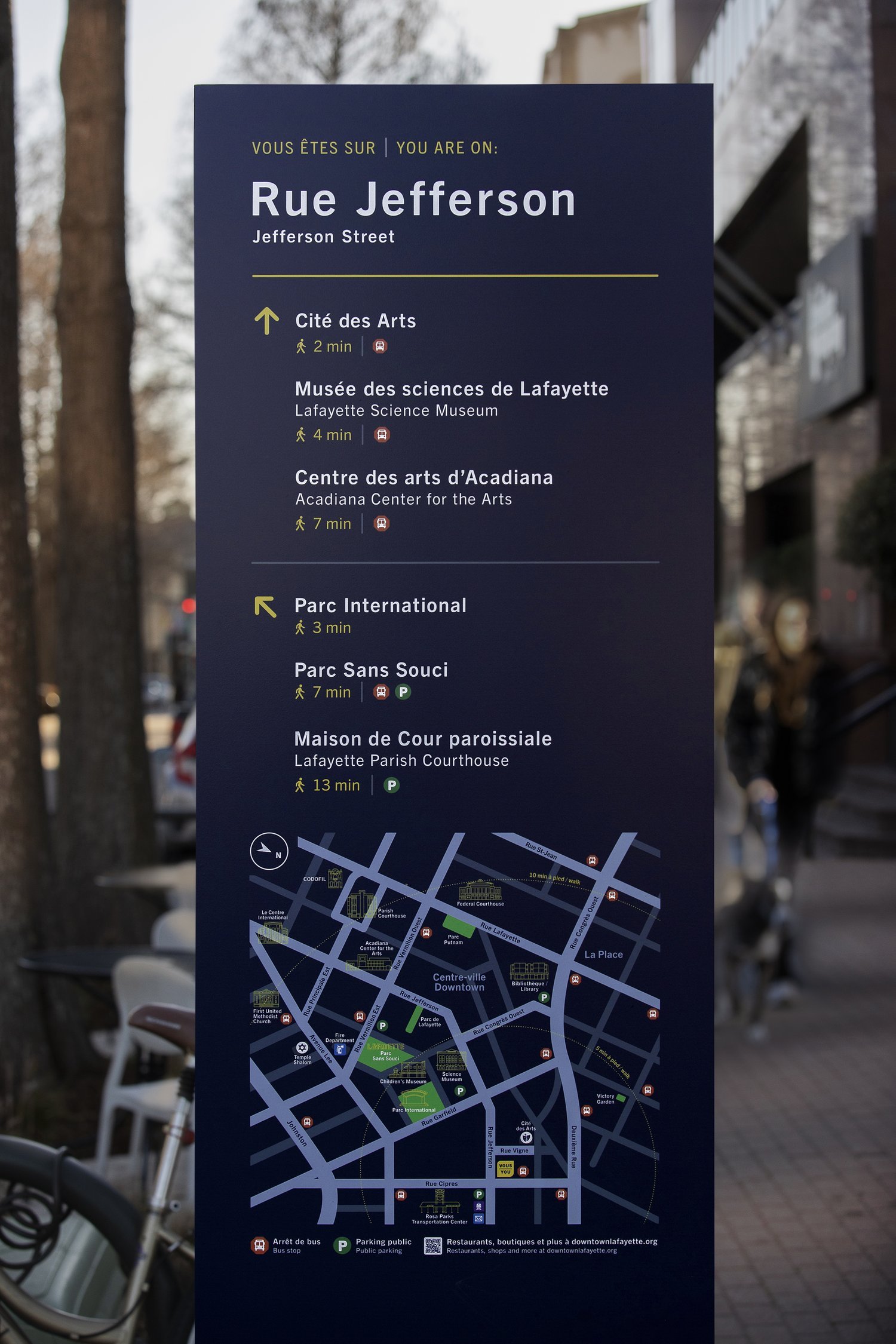

In 2021, Stephen Ortego worked with Makemade and Lafayette Consolidated Government to design and implement bilingual signs in downtown Lafayette. Jonathan Olivier/Télé-Louisiane

This article is Part 2 in a series on French in Louisiana. Part 1, which explains the complexities of French immersion in Louisiana, is available here.

By Jonathan Olivier

Renée Reed began learning French when she was around five years old at Evangeline Elementary School, an immersion program in Lafayette. Although she left the program just a year later, French remained in her life through learning Cajun music and spending time with her grandparents who are native speakers of Louisiana French.

“I remember a period in my life when I was little, speaking mostly French at school,” she said. “And then when I’d go to my grandparents, because I’d go to my grandparents a lot, we would speak French.”

Despite Reed’s familial link to French, English was still her mother tongue. Given that English had become the region’s dominant language for a few decades by the time she was growing up in the early 2000s, it was easy for French to take a background role. Then, in high school, she began playing Cajun music with her mom, Lisa Trahan, who plays with the Magnolia Sisters, and her dad, Mitchell Reed, who played with BeauSoleil. Later on, as a student at the University of Louisiana at Lafayette, she majored in French and music.

Due to the various ways Reed had learned the language, she had created a patchwork of French competencies. In order to form a more solid base, in 2019 when she was 20, she participated in a five-week immersion program at the Université Sainte-Anne in Nova Scotia, Canada. Participants could only speak French for the duration of the program, during classes and a variety of workshops, games and extracurricular activities.

“That's where you're really learning is when you're in real life with the language,” said Reed, now 24. “And I had never been in those kinds of situations before. And so, in that experience, I was learning more than I was even processing. By two weeks in, I could really talk and I wasn't even aware of how much I was learning.”

Renée Reed plays with several Cajun music groups in Lafayette, as well as a solo act that allows her to write music in French. Courtesy of Renée Reed.

Reed is what linguists in Europe who study minority and heritage language revitalization call a “new speaker.” Typically, this refers to someone who has had little home or community exposure to a heritage language, and who then acquires it via immersion education or language revitalization projects.

In the last few decades, French has been principally passed down to younger generations of Louisianans like it was for Reed—through immersion education as children or adults. Many native speakers of Louisiana French are often elderly, usually older than 60, yet many more are in their 70’s or 80’s. As this demographic continues to age, in the near future new speakers of French in Louisiana will comprise the bulk of the francophones in the state.

This generation of new speakers, often younger than 40, represents a generational shift that developed after home transmission of French faded in the mid to late 20th century. Their grandparents likely spoke French as a first language, and their parents are likely anglophones with some knowledge of French. This contact with native speakers of Louisiana French, although often limited, gives new speakers the ability to grasp what they can and pass it on, according to Stephen Ortego, a Lafayette-based architect who, as a teenager, also studied at Université Sainte-Anne.

“Our generation is a sort of bridge between our grandparents who almost all spoke French and the next generation,” said Ortego, 39, from Carencro. “It’s up to us to transfer the language to this next generation. And it’s important to have a certain percentage of us who continue what makes us special.”

In order for French to continue to remain viable with this new generation, folklorist and professor emeritus at the University of Louisiana at Lafayette Barry Ancelet wrote in a 1988 essay that there must be the development of a “French environment.” This includes a society where French is institutionalized and visible alongside English, including the existence of radio and television programs, magazines, books, billboards and road signs. “If someone is to bother learning French,” Ancelet wrote, “there must be something worth doing, reading, seeing, and hearing in the language.”

For much of the decades following Ancelet’s call to restore French in the state, his francophone environment failed to gain steam. Yet, in the last few years, there has been a flurry of progress thanks, in large part, to former French immersion students. Scattered about south Louisiana are signs of new life that is nurturing French within the state’s wider society through infrastructure, music and art.

Building a French Environment

Ortego heard French often when he was a kid, spending time in Washington or Opelousas with his French-speaking grandparents, neighbors and extended family. But he wasn’t immersed in a society where French is institutionalized until, at age 19, he attended Université Sainte-Anne’s immersion program. It was there that he began dreaming in French, thinking in French, all without effort. This, Ortego said, provided him with a solid base of the language so that he could return to Louisiana with the linguistic skills to live in French.

“Afterwards, I continued to speak in French with my grandparents, neighbors and friends,” he said. “I made friends my age who were in immersion. I refused to speak in English with people in Louisiana who I knew spoke French because I wanted to learn. It was the only way to learn.”

Only a few years later, Ortego served as a state representative, from 2012 to 2016. During that time, he invested in institutionalizing French in Louisiana. Ortego’s House Bill No. 998 in 2014 allowed parish governing bodies, either police juries or parish councils, to ask the Louisiana Department of Transportation and Development (DOTD) to provide bilingual signs along state and federal highways. The bill was ultimately signed into law by Governor Bobby Jindal, becoming Act 263, which first tasked DOTD with adopting changes to the Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices (MUTCD) to include bilingual signage.

Bilingual signs were installed in Lafayette in 2021 thanks to Makemade, SO Studio Architecture and Lafayette Consolidated Government. Photos of signs courtesy of Makemade.

“We had already started talking with several parish presidents or presidents of the police jury in the 22 parishes of Acadiana,” Ortego said. “We had the intention that as soon as the policy was adopted by DOTD, we wanted to go to each parish and talk with the police juries or the parish councils.”

According to Ortego, DOTD never took steps to adopt the changes to the MUTCD. So, nearly 10 years later, local parishes still don’t have the opportunity to adopt bilingual signs. Yet, Ortego made progress on this front in 2021. His firm SO Studio Architecture was able to work with Makemade and Lafayette Consolidated Government to install bilingual wayfinding and street signs throughout downtown, called the Route Lafayette project.

While these signs exist only around downtown Lafayette at the moment, Ortego’s firm and Makemade also took some of the steps that DOTD has not, making changes to the MUTCD that features bilingual signs that go beyond wayfinding, such as stop signs. If the parish government would decide to adopt these changes parish-wide, Ortego said the document outlining changes to the MUTCD would provide a pathway to do so. On the state level, Ortego emphasized that, legislatively, everything is in place for DOTD to expand bilingual signage.

“Maybe there are people who can ask their state representatives to return to this question and push more to maybe provide money to DOTD to adopt the policy that is already written in law,” Ortego said. “So, if it’s financed, there aren’t any more excuses.”

A Bridge to the Next Generation

Philippe Billeaudeaux was part of the first French immersion class in Lafayette in the early ‘90s at S.J. Montgomery Elementary School, which is now housed at Myrtle Place Elementary. Billeaudeaux continued on to Prairie Elementary School and then Paul Breaux Middle School, while he also heard some French at home from his father.

“I have continued using French in my creative projects,” said Billeaudeaux, 37, from Lafayette. “I play Cajun and Creole music with Feufollet, Steve Riley and Cedric Watson. I also do a cartoon in Louisiana French with filmmaker Marshall Woodworth, who lives in New Orleans. We created ‘Les Aventures de Boudini et Ses Amis,’ a cartoon for immersion students.”

Boudini, a project between Billeaudeaux and Woodworth’s Creole Cartoon Company and Télé-Louisiane, first aired online in January 2021. This year, a new season of the series will air on Louisiana Public Broadcasting. With characters voiced by Louisianans like long-time immersion teacher and poet laureate of French Louisiana, Kirby Jambon, and musicians Cedric Watson and Louis Michot, immersion students have the opportunity to hear Louisiana French from within the local francophone community.

Philipe Billeaudeaux (left) and Marshall Woodworth created the cartoon “Les Aventures de Boudini et Ses Amis,” which provides immersion students a way to learn Louisiana French. Courtesy of Philippe Billeaudeaux

In the last few years, there has been an uptick in projects led by former immersion students. In 2018, a podcast called “Charrer-Veiller,” was founded by Joseph Pons and Chase Cormier; Drake LeBlanc, the chief creative officer and co-founder of Télé-Louisiane, and Jo Vidrine, a staff photographer, participated in Lafayette’s immersion schools; and “Le Bourdon de la Louisiane,” an online news journal, was founded in 2018 by former Sainte-Anne student Sydney-Angelle Dupléchin Boudreaux and also Bennett Boyd Anderson III.

Around Lafayette, a few organizations target immersion students in order to provide examples of French existing outside the classroom. At Vermilionville, Lafayette’s living history museum, the staff is again hosting a summer camp in July for French immersion students. Zach Fuselier, a former immersion student, works at Vermilionville as the heritage gardener where he tends to the museum’s animals and garden, offering presentations virtually every day in French.

“Often, we have tourists from Canada and France and other French-speaking countries,” said Fuselier, 26, from Lafayette. “So, I can share my culture with them and I can do it in French. It’s a language that they’re most comfortable in. And I can show them that there are still people who speak French in Louisiana.”

Despite the recent projects of some former immersion students, Fuselier said that the majority of his former classmates likely don’t use the language in their everyday life. Life outside of school often exists solely in English—even for him, English is the language he uses the most in his life. That’s why it’s even more important, he said, to nurture a francophone environment so that immersion students, both current and former, continue to exist in the language after they leave the classroom.

“We’ve got to provide an incentive for children, first to learn the language and second to use it in their everyday life,” he said. “If we want to bring back French, we have to have more resources, just to live in French.”

Developing New Francophones With French Immersion Schools

More than 5,000 children are learning French through immersion in Louisiana, establishing a small but growing population of new francophones across the state.

More than 5,000 children are learning French through immersion in Louisiana, establishing a small but growing population of new francophones across the state.

This article is Part 1 in a series on French in Louisiana. Part 2, which explores how former immersion students are using their language skills to support French in the state, will be published on May 9.

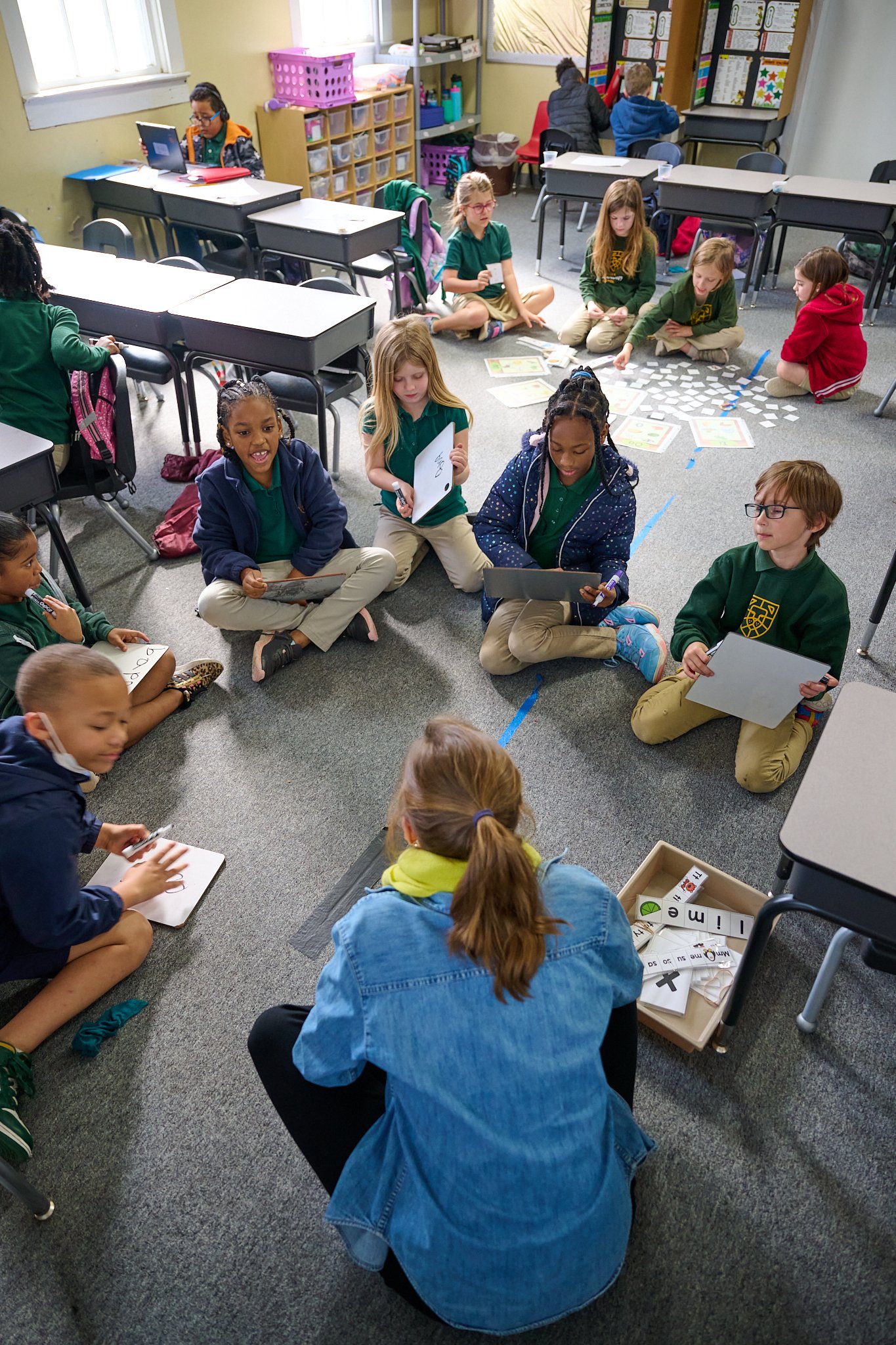

Story by Jonathan Olivier | Photos by Jo Vidrine

In the middle part of the 20th century, home transmission of French began to rapidly decline in Louisiana—what linguists call a “language shift,” as English became the dominant language spoken at home and throughout the state’s communities.

According to 1990 census data, more than 80 percent of self-identified Cajuns born at the turn of the 20th century still spoke French as their first language at home, according to Shane K. Bernard in his book “The Cajuns: Americanization of a People.” That figure fell to 21 percent for those born between 1956 and 1960, and even lower to eight percent for those born between ‘71 and ‘75. “A similarly dismal number spoke French as a second language,” Bernard wrote. While this doesn’t represent all francophone groups in Louisiana, it does offer an idea of the extent of the language shift that occurred in the 20th century.

This trend continued for decades so that, these days, French has essentially disappeared as a first language learned at home or spoken at large throughout communities. Instead, French is now typically learned by monolingual anglophone children as a second language in French immersion schools, where they learn an academic, standard variant of the language. Therefore, immersion has become one of the most important and viable ways to grow a population of new francophones in Louisiana.

“We have kindergartners who are speaking full sentences to us in French by Christmas, telling us what they need,” said Lindsay Smythe, school leader at École Saint-Landry, an immersion charter school in Sunset. “And they can remain and participate in French all day long.”

At École Saint-Landry, children who are typically monolingual anglophones begin in kindergarten where they spend the majority of their day learning in French through courses like math and science. Usually, they are only taught in English during English Language Arts classes.

Founded in 2021 as a full immersion campus with kindergarten and first grade, École Saint-Landry currently houses kindergarten through second grade. Smythe said they’ll continue adding grades as their current group of students progresses each year, eventually offering up to the eighth grade.

In 2010, immersion students totaled 3,416 statewide. Today, the 103 students currently enrolled at École Saint-Landry are among more than 5,100 children who participate in French immersion at more than 35 schools across the state. They have joined the thousands more who have participated in immersion over the last three decades. Several thousand more have participated in immersion programs as adults, most notably at the University Sainte Anne in Nova Scotia, one of the Acadian provinces of Canada.

Yet, immersion is still a niche effort that exists within a wider anglophone education system. Immersion students make up less than one percent of Louisiana’s school-age demographic—there are around 1 million children under 18 in the state. So, growing the number of schools that offer a program has been a priority of language activists and educators for years now.

According to Michèle Braud, world languages specialist at the Louisiana Department of Education, state officials involved with immersion would like to continue expanding enrollment by five percent each year. Although Braud’s department is still compiling numbers from the 2022-2023 academic year, she said enrollment is up.

In August 2023, three more programs will open: École Pointe-au-Chien in Pointe-aux-Chênes will become the first program serving a predominantly Indian French population; Evangeline Reimagine Academy will open in Ville Platte thanks to Louisiana’s Reimagine School Systems Grant; and Fairfield Elementary Magnet School will be the first program in Shreveport.

The Beginning of French Immersion Schools in Louisiana

James Domengeaux, who in 1968 was pivotal to the establishment of the Council for the Development of French in Louisiana (CODOFIL), often said that “L’école a détruit le français; l’école doit le restaurer.” “School destroyed French; school must rebuild it.” Of course, what Domengeaux was referring to is that French in Louisiana experienced such a rapid decline in the 20th century, in part, due to the 1921 state constitution that made English the official language of the classroom. This resulted in French being barred from schools—corporal punishment was often inflicted on children who spoke the only language they knew in order to force them to learn English.

Domengeaux’s vision was to reestablish the language throughout Louisiana’s communities via education. In the 1970s, CODOFIL initially instituted this plan through French language classes for short durations during the school day—the results proved to be unpromising. Domengeaux then looked to Canada, and he learned of experimental yet successful French immersion schools that, instead of teaching students French as a language class, taught them most classes in the language itself. Domengeaux’s interest led to a pilot immersion program in Baton Rouge in 1981. Yet, the programs didn’t really begin to take off until the ‘90s.

In the early 2010’s, CODOFIL’s mission was amended through a series of laws. In 2010, former Senator Eric Lafleur, D-Ville Platte, introduced Act 679, which passed to redefine CODOFIL’s purpose. The agency was specifically tasked with enhancing Louisiana’s French immersion schools in coordination with the Louisiana Department of Education and the Louisiana State Board of Elementary and Secondary Education through the International Associate Teacher Program.

Establishing an immersion program in a Louisiana school district is possible thanks to legislation passed in 2013. Act 361, called the “Immersion School Choice Act,” states that parents or legal guardians of at least 25 pre-school aged children who live in a particular school district need to sign a petition, and state law dictates a school board must create an immersion program. Unfortunately, the law has no enforcement mechanism, and at least four petitions have gone unanswered by local school boards: two in St. Tammany Parish and two Terrebonne Parish. Braud with the LDOE said that the more successful tract to opening a program is for parents to simply begin a conversation with the school district, CODOFIL and LDOE.

Typically, a program is housed within a traditional, English-language school that offers a French immersion tract. Some schools only offer French immersion, such as École Saint-Landry. There are only a handful of options for high schoolers who want to continue in immersion, such as Lycée Français in New Orleans and Lafayette High in Lafayette.

French in an Anglophone Curriculum

Rebuilding French after several generations of language shift hasn’t been an easy task. The lack of home transmission means that Louisiana doesn’t have an adequate pool of francophone educators who are certified. So, CODOFIL and its partner agencies coordinate with foreign governments to provide U.S. Department of State’s J-1 visas to teachers who instruct in Louisiana for a three-year period, which can be extended for two more years. The state has formal agreements for teacher exchanges with France, Canada, and Belgium, and teachers also come from other countries too, increasingly from Francophone Africa.

The reliance of foreign teachers means that students often don’t hear Louisiana French in the classroom, as educators are unaware of its regional variances. The state’s Minimum Foundation Program (MFP) also caps the number of foreign teachers that can instruct in immersion in Louisiana at 300. Therefore, priority is given to elementary programs. The MFP cap, plus high rates of attrition among immersion students post middle school, have led to the creation of only a handful of high school immersion programs.

In order to expand her burgeoning school, Smythe with École Saint-Landry would like to see the state law changed to remove the MFP cap. Because, as of now, expanding her school beyond eighth grade would be a challenge—she’d have to find local teachers who are francophone and certified to teach, which she said can be difficult in small towns like hers.

Foreign teachers are also tasked with navigating Louisiana’s curriculum standards. Each school is subject to its local school district’s curriculum, which is often written in English. “So, if a parish adopts a math curriculum, if that math curriculum does not exist in French, it is on the shoulders of the immersion teachers to translate the entire curriculum into French,” Smythe said.

Smythe said she’d like to see the creation of a state-wide French language arts curriculum that could be applied to all of the French immersion schools. However, some schools, such as Audubon Charter School in New Orleans, follow both Louisiana and French national academic standards, the latter set forth by the French Ministry of Education that is part of Agency for French Teaching Abroad (AEFE).

According to Sophie Capmartin, French program director at Audubon, her students learn using books and materials purchased from France. “The work on a French curriculum allows a greater openness to the world and brings an intercultural perspective on certain themes or in the way of approaching certain disciplines,” Capmartin said. “The texts in French literature are integral works of French-speaking authors that students study as soon as the third grade.”

Capmartin noted that students at Audubon typically score above or on the French national average on the French national exam, which certifies someone’s French language abilities. In general, immersion students tend to perform better on standardized tests than their monolingual peers.

Despite the challenges of reestablishing French within an anglophone educational system, Smythe said she recognizes the many benefits her students are receiving. Plus, she feels she is doing her part in reconnecting her students to a unique linguistic heritage.

“As a French speaking society, I personally feel very honored to be a part of what we’re doing,” Smythe said. “Anybody who is bilingual, they're just going to have more opportunities, they're going to have more doors open. I'm just so pleased that we were able to bring this to our students, because they didn't have that opportunity before, and now they do.”

Tu Vis Ta Culture ou Tu Tues Ta Culture

With his latest album, Jourdan Thibodeaux implores Louisianans to hold on to their heritage.

With his latest album, Jourdan Thibodeaux implores Louisianans to hold on to their heritage.

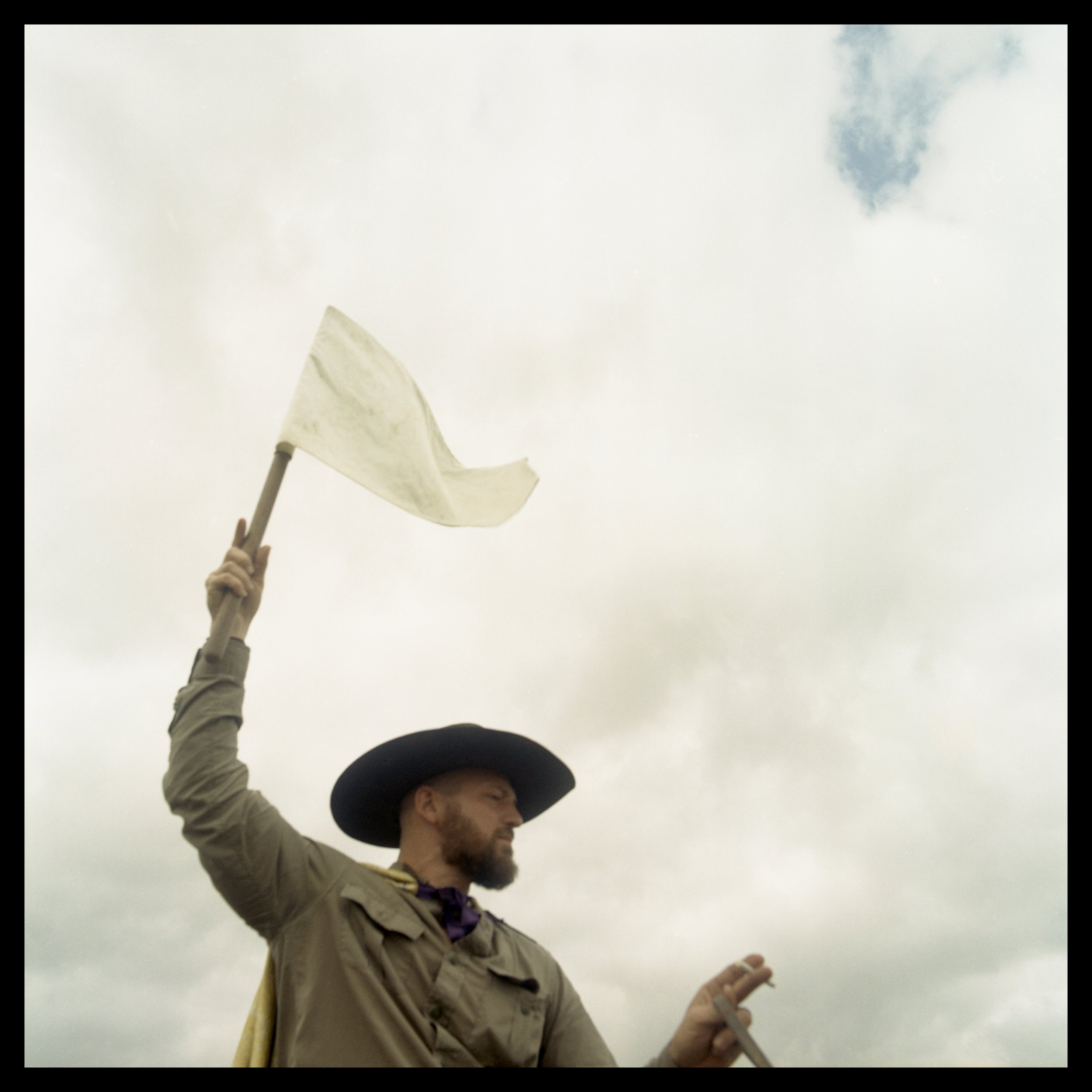

Jourdan Thibodeaux’s new album, La Prière, was released in March 2023. Drake LeBlanc/Télé-Louisiane

This article was published in partnership with Country Roads Magazine. It is available in print and online here.

By Jonathan Olivier

Last October, Lafayette’s Festivals Acadiens et Créoles closed out Saturday night with a performance by Jourdan Thibodeaux and his band Les Rôdailleurs. The set included hits from Thibodeaux’s 2018 debut album, which has earned him a following at home and afar, as well as a mix of new tunes anchored by his French lyrics.

His last song of the night, also the title from his sophomore album released this spring, La Prière, didn’t conform to typical closers. Instead, it was slow, rhythmic, solemn. The crowd, which had spent the day two stepping and waltzing, turned to the stage in reverence. Many swayed back and forth. Among those who could understand Thibodeaux’s French lyrics, there were even tears.

In the first lines, dubbed over an interview with Thibodeaux’s late grandfather Charles Herbert, he chants: “Tu vis ta culture ou tu tues ta culture, il n’y a pas de milieu.” “You live your culture or you kill your culture, there is no in between.”

In the song, Thibodeaux acknowledges the young Louisianans who cannot understand his lyrics, people who have forgotten Louisiana’s traditions and its language, and those who only speak, as he sang, “la langue de les conquis,” or the language of the conquered—English.

At the core of La Prière, which means “The Prayer,” Thibodeaux invokes that the French language—and the culture that sustained it—will not fade away into history. He prays that people continue to actively participate in Louisiana’s rich cultural heritage. And he prays that his generation won’t be the last to live it.

While La Prière is a somber reminder of how much Americanization has changed Louisiana, it’s also a rallying cry to assemble all the cultural pieces that former generations left behind, in order to preserve and perpetuate the qualities that make Louisiana so unique. This call to action, in large part, is Thibodeaux’s life’s work.

“People are always saying, ‘I’m Cajun’ or ‘I’m Creole.’ And they’re really proud of that,” he said. “But you can’t only have the title. If you want the title, you need to keep everything associated with it. You need to keep the language, the culture, the religion—because it’s all connected.”

Thibodeaux learned French from his grandmother, Lucille “Hazel” Blanchard. In order to pass the language to his two daughters, he speaks French to them at home, ensuring that, in his family, the over-three-hundred-year-old linguistic chain remains unbroken. He sticks to traditions that he was raised with—such as Roman Catholicism, hunting and gardening, and local customs like “pâquer,” which features knocking eggs together in a game played at Easter.

“We need to pass all that we have been given from other people to the next generation,” he said

Jourdan Thibodeaux et Les Rôdailleurs at Festivals Acadiens et Créoles in October 2022. Photo courtesy of David Simpson

La Prière’s original 2020 release was delayed due to COVID-19. Thibodeaux, who plays fiddle and sings, released the album with Eunice’s Valcour Records with his band Jourdan Thibodeaux et Les Rôdailleurs, which he founded in 2018. Today, the band consists of renowned musicians Cedric Watson, Joel Savoy, Alan Lafleur, and Adam Cormier.

While many local artists who sing in French today record remakes of older songs, or stick to traditional notions of what Cajun or Zydeco music should sound like, Thibodeaux writes his own music, on his own terms. His songs are heavy on the fiddle and feature prominently his raspy Louisiana French lyrics. For La Prière, Thibodeaux and his band cut songs from a list of around 40 that he has written over the course of the last several years. “I recorded the songs I feel the most at the moment,” he said.

The resulting album represents snippets of the musician’s life in Cypress Island in rural St. Martin Parish, much of it spent tending to horses and working outside. When people ask him what sort of music he plays, Thibodeaux usually responds: “Louisiana French music.”

“When I was younger, that’s what my grandmother called it,” he said. “It was just French music and it was the music of the country. It was never ‘Cajun’ or ‘Creole’. Because everyone here was the same people. We were one culture.”

Many French and Creole-speaking Louisianans were ushered into mainstream America only a few decades ago; the remnants of the once-isolated, regional culture of south Louisiana are dwindling, but they do still survive. Thibodeaux believes holding fast to these old traditions—the language, food, music, and cultural practices—serve as a guide to approach the future. And perhaps that’s the lasting message of La Prière—respect heritage traditions, and continue them with all that you’ve got.

“How are you going to know where you’re going,” Thibodeaux said, “if you don’t know where you come from?”

Acadian Musicians Lisa Leblanc, Les Hay Babies Find Inspiration in Louisiana

The New Brunswick-based artists return to Louisiana this month to play at Festival International de Louisiane. The region, although separated by thousands of miles and hundreds of years of cultural history, still feels like home.

The New Brunswick-based artists return to Louisiana this month to play at Festival International de Louisiane. The region, although separated by thousands of miles and hundreds of years of cultural history, still feels like home.

in 2018, Lisa LeBlanc played at Festival International de Louisiane. Photo courtesy of David Simpson

By Jonathan Olivier

Acadian musician Lisa LeBlanc first visited Louisiana in 2015 to play at Festival International de Louisiane, one of the state’s biggest music festivals. Later that year, she returned for Blackpot Festival where she camped out for a week at Blackpot Camp in Eunice with other musicians from Louisiana and afar.

Louisiana’s music, food, culture and regional French dialect left an indelible mark on the award-winning musician from New Brunswick, so much so that the Bayou State has become a place of inspiration.

“I love Lafayette and it makes me think of Moncton [New Brunswick],” LeBlanc said. “From the first moment that I arrived in Louisiana, it was like I was back at home due to the similarities and the music. There are a lot of similarities between us, the Acadians of the north, and the Acadians of the south.”

LeBlanc is returning to Louisiana this month to play at Festival International de Louisiane for the fifth time. While past appearances have featured her self-described “trash rock” folksy sound, this year she’ll also play songs from her latest album “Chiac Disco” that she released in 2022. Her new music is devoid of banjo and more reminiscent of funk genres from the ‘60s or ‘70s.

LeBlanc returns to Festival International this year, taking the stage Friday and Saturday night. Photo courtesy of David Simpson

“Honestly, I’m really flabbergasted by the reaction to this album,” she said. “We didn’t really know what would come of it. Because, honestly, this kind of album kind of came out of nowhere. It’s super different from what I’ve done in the past.”

Although LeBlanc’s sound has shifted with Chiac Disco, the album’s vibe is not much of a departure from past hits like “Aujourd’hui ma vie c’est d’la marde”—LeBlanc’s new music still showcases her voice’s unique tone, as well as her vibrant personality. Chiac Disco has been a hit with fans across the francophone world, bringing her to Europe to tour several times since the album’s release.

“All of a sudden, I’m finding myself with such a magnificent reception,” she said. “I couldn’t be happier with everything. We are really lucky.”

The Acadian group Les Hay Babies, composed of Vivianne Roy, Julie Aubé and Katrine Noël, also from New Brunswick, will return to Festival International this year for the second time. Like LeBlanc, during the group’s previous trips to the state, it was easy to find similarities between their culture and Louisiana.

“I find that in Louisiana, there are so many familiarities,” Roy said. “It’s as if we could enter a totally parallel world.”

Noël added: “We say all the time that our friends we make who are from Lafayette, it’s like, ‘This is the Louisiana version of someone from back home.’ It’s like everyone has a Louisianan or Acadian counterpart.”

Les Hay Babies return to Festival International de Louisiane this year for the second time. Photo courtesy of Marc-Étienne Mongrain

The group rented a space for a week in Henry, near Erath, Louisiana, in order to record their next album, using the region as inspiration. The trio, which normally plays rock, has no plans for what this new record will sound like—they’re waiting on motivation from Louisiana’s countryside and plan to cut a few songs with local musicians.

“If there are any people who want to come talk to us in French after our show, if anyone sees us at the festival, or if anyone wants to tell us some stories, we’ll take any inspiration that we can have for our album,” Noël said.

Festival International de Louisiane kicks off on April 26, ending on April 30. The event is free and sprawls across downtown Lafayette. Lisa LeBlanc will play on April 28 at 8:30 p.m. at the Scène Laborde Earles Fais Do Do, and on April 29 at 6 p.m. at the Scène LUS Internationale. Les Hay Babies will play on April 29 at 4:30 p.m. at the Scène Tito’s Handmade Vodka, and on April 30 at 3:30 p.m. at the Scène Laborde Earles Fais Do Do.

For more information on Festival International de Louisiane, find the full line up here.

Cajun Mardi Gras in the Prairie of Faquetaique

Lafayette-based photographer Kristie Cornell has participated in the Faquetaique Courir de Mardis since 2009. This year, she captured the tradition in a series of analogue photos.

Lafayette-based photographer Kristie Cornell has participated in the Faquetaique Courir de Mardis since 2009. This year, she captured the tradition in a series of analogue photos.

By Kristie Cornell

In 1997, I attended and photographed my first Courir de Mardi Gras, which was the Tee Mamou/Iota women’s run. In the years following, I continued on and off to follow and photograph various courirs, including those in Soileau, Elton, Jennings and Eunice, but always as a spectator. In 2009, I participated in the Faquetaique Courir de Mardi Gras, carrying my camera and capturing images from the perspective of a participant rather than that of a bystander.

Over the years, my personal photography had been a mix of film and digital, but for speed and ease I always opted to carry my digital camera when photographing at Faquetaique. By 2020, I had grown tired of digital images and had fully transitioned back into analog photography. So, in 2023, I decided to try to shoot the courir on film with my medium format Hasselblad 500c. This is no easy task–carrying a heavy camera while walking all day, and framing images on the ground glass while wearing a mask. But I love every minute of it.

I have continued to run Faquetaique every year since 2009, always photographing with the intention of documenting my friends and the ridiculousness that happens during the course of a Mardi Gras day. In capturing these images each year, I hope to preserve the memory of the day for all of us who actively participate in upholding our culture and traditions.

Kristie Cornell is a self-taught photographer living and working in Lafayette, Louisiana. Her work explores her relationship to the natural and cultural landscapes of her native Louisiana and the South, as well as connections made to places she explores while traveling. Her photographs have been published in several books and as album artwork, and her work has been shown at many galleries across Louisiana. Additional work can be found at www.kristiecornell.com, or on Instagram at @kccornell.

Washed Away

Construction of the Mid-Barataria Sediment Diversion is set to begin this year to restore wetlands, but the project will have adverse impacts on the region’s fisheries used by fishermen like Jason Pitre, a member of the United Houma Nation.

Construction of the Mid-Barataria Sediment Diversion is set to begin this year to restore wetlands, but the project will have adverse impacts on the region’s fisheries used by those like Jason Pitre, a member of the United Houma Nation.

Story by Jonathan Olivier | Photos by Jo Vidrine

Jason Pitre piloted his boat out of Bayou Lafourche near Leeville, speeding through marsh towards Little Lake where his oyster fishing grounds sprawl across seven acres. This particular lease goes back three generations in his family, last farmed by his late grandfather Antoine “Whitney” Dardar.

Back then, Dardar caught oysters from his pirogue just like his Houma ancestors had. He used a push pole to navigate the small ponds, canals and the nearby Bayou Rosa, the inspiration for Pitre’s current oyster business, Bayou Rosa Oysters.

As Pitre rode towards Dardar’s old fishing grounds, the wetlands that surrounded him would be unrecognizable to his grandfather’s eyes—Bayou Rosa is wider and degraded, and Little Lake has grown so large that today’s southwest wind lapped up waves that risked swamping Pitre’s 21-foot boat. Large expanses of open water have replaced nearby bayous, ponds and protected inlets, part of more than 2,000 square miles of wetlands that have disappeared in Louisiana since the 1930s. Scientists predict 4,000 square miles more will disappear in the coming decades if nothing is done.

As climate change worsens, hurricanes have become stronger, a reality that forced Pitre to move his family from his hometown of Cutoff to Raceland, a town farther north that is more protected from the Gulf of Mexico. Pitre, a member of the United Houma Nation, said other Native Americans in the region have made the same decision to abandon ancestral lands to escape the dangers of a vanishing coast.

“With each hurricane, people decide this is too much,” Pitre said. “So, the culture in the community leaves one area. It kind of gets dispersed. So over time, our traditions keep dying. As coastal erosion continues and the lands are diminishing, culture and history is slowly kind of washing away, too.”

The Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority (CPRA) has implemented various projects over the years to mitigate further damage to the region’s wetlands, part of the state’s 50-year, $50 billion Coastal Master Plan. This summer the CPRA is beginning construction on a project at a scale never before attempted—the $2.92 billion Mid-Barataria Sediment Diversion. The state will install a structure on the Mississippi River near Ironton in Plaquemines Parish that can open at certain times of the year, allowing 75,000 cubic feet per second of river water and sediment to flow through a 2-mile-long concrete channel into the Barataria Basin.

According to state officials, the project is poised to build 21 square miles of new land in 50 years, which will eventually represent 25 percent of all the wetlands left in the Barataria Basin by 2070. Officials expect the project will be completed in at least five years.

While the idea of building land sounds promising to a coastal inhabitant like Pitre, in an unfortunate twist of fate, the sudden influx of freshwater from the diversion will have “major, permanent, adverse impacts” on the oysters in the Barataria Basin, according to an environmental impact statement released by the Army Corps of Engineers. Sediment will cover oyster fishing grounds while freshwater will make many oyster beds in the basin unproductive. The diversion will also adversely impact brown shrimp populations while it’s projected that 97 percent of the 2,000 bottlenose dolphins in the Barataria Basin will die.

Pitre’s oyster lease is just west of Bayou Lafourche in the Terrebonne Basin, which borders the diversion impact area. Still, he fears he is close enough to the diversion that with an east wind he’ll see some effects, enough so that he’s concerned the future of his business is at risk.

“It's like accepting the fact that you have stage 4 cancer and you're going to die,” Pitre said. “Well, I'm going to at least try to live my life as long as I can.”

The Losses in the Barataria Basin

Between 1974 and 1990, roughly 5,700 acres per year washed away in the Barataria Basin due to a combination of factors: sea-level rise and natural factors like wind and wave erosion, but also the result of human activities. According to a recent study published in the journal Nature Sustainability, levees along the Mississippi River, plus oil and gas wells and canals, are the most prominent reasons why land in the Barataria Basin is vanishing. Drilling and then the canals dug to reach those oil wells caused erosion and subsidence issues. And without the freshwater and sediment that was once regularly deposited by the now contained Mississippi, the marsh continued to wash away without a way to rebuild.

Officials with the CPRA contend that the Mid-Barataria Sediment Diversion will mimic those natural processes that existed before the levees were constructed. Bren Haase, executive director of the CPRA, noted that the Barataria Basin is starved of freshwater and sediment, and the diversion will essentially breathe new life into a dying ecosystem. “A project like this is going to hit reset on that kind of fresh, salt water balance, which is needed,” he said.

Doing nothing is too great of a risk, Haase said, because without the diversion, issues would only be exacerbated. Scientists warn 550 square miles of marsh would disappear in the Barataria Basin in the next 50 years if nothing is done. Less marshland would leave coastal communities more vulnerable to hurricanes. The Barataria Basin would continue to lose productivity—according to the Army Corps’ assessment, half as many oysters and 30 percent fewer shrimp are caught in the basin compared to 20 years ago. Eventually, the oyster and brown shrimp industry would be crippled anyway.

Yet, the Army Corps report also noted that changes to the fishing industry in the basin will occur “decades sooner” with the diversion in place. Due to this reason, George Ricks, a charter boat captain from Plaquemines Parish and president of the Save Louisiana Coalition, is strongly opposed to the Mid-Barataria project. With or without a diversion, the fisheries in the basin will be permanently altered, but for Ricks, the difference is timing.

“If we don't do anything, in 50 years we're going to lose the fisheries anyway,” said Ricks, who has been an outspoken critic of the Mid-Barataria Sediment Diversion for years. “But give us that 50 years. Don't kill us now. And that's exactly what they're going to do with this project.”

Ricks would rather that coastal communities have more time to adapt to the changes occurring in the Barataria Basin. To combat land loss, he would prefer that the state dredge sediment and pump it into the basin to build land and barrier islands. The CPRA already employs this tactic across the coast, including in the Barataria Basin, but the agency doesn’t view it as a long-term, sustainable option. The diversion, on the other hand, would theoretically offer a seemingly endless supply of sediment from the Mississippi River.

Yet, if the idea is to build land, Ricks doesn’t see how 21 square miles of it built in 50 years is a suitable solution. Hurricane Ida, for example, destroyed more than 100 square miles of wetlands essentially overnight, much of it in the Barataria Basin. From his point of view, the expected benefits of the project aren’t worth the cost or the sacrifice that coastal communities will endure. Part of the Barataria Basin falls in Plaquemines Parish, which is home to the largest commercial fishing fleet in the continental United States. He pointed out that 70 percent of the oysters, shrimp, crabs and fish sold commercially in Louisiana comes from the fishermen in Plaquemines Parish.

“The minute they open the gates to this project,” Ricks said, “they're going to put people out of work.”

Finding Ways to Adapt

When the wind calmed and it was safe to put out a few traps in Little Lake, Pitre navigated to a spot on his oyster lease and readied a cage. In a bucket nearby he had hundreds of tiny oysters that he loaded in his cage before tossing it overboard. He uses a method to grow oysters called Alternative Oyster Culture (AOC), which features growing oysters in cages that are submerged yet suspended off the bottom of the marsh, instead of the more traditional method where oysters grow on hard surfaces underwater.

Rather than relying on wild oyster larvae, Pitre purchases thousands at a time that are grown at hatcheries, such as from Triple-N-Oysters that cultivates them miles from the sea in Baton Rouge. Since Pitre’s oyster cages either float or are suspended, there is a small element of mobility that he has which otherwise wouldn’t exist in more traditional operations that rely on underwater structures.

This flexibility means that he might be able to salvage Bayou Rosa Oysters when the diversion opens. He’s eyeing oyster leases that are farther west, which will likely have more stable salinity levels compared to his current lease. He’ll be able to pack up his traps, move to a new lease and have new oyster harvests in a relatively short period of time.

In a future with regular influxes of sediment-laden freshwater from the Mississippi River in the Barataria Basin, traditional oyster beds might be covered in mud. Pitre said since AOC doesn’t require underwater structures, it could provide some people who lose traditional oyster beds with a way to continue catching, as long as the salinity levels are right.

In order to mitigate the damage caused by the diversion to oyster beds and fishing grounds, as well as those who will be impacted by flooding, state officials are setting aside more than $370 million. Haase with the CPRA noted that part of this money will go toward incentives for AOC operations like Pitre’s, as well as opening new oyster fishing grounds wherever possible. “So, a person who might have an oyster bed that's in a place that would become unproductive because of the diversion can go and reseed and put cages down in an area that may be more productive,” he said.

Even still, AOC isn’t a fix to the anticipated problems of the diversion’s freshwater. “No matter how much money you give, if you completely turn the water fresh, I can't function,” Pitre said. “I can't do anything with that.” Plus, for Pitre, leaving his grandfather’s oyster grounds isn’t an easy decision to make. Catching oysters in Bayou Rosa isn’t a business decision, it’s one rooted in his heritage.

With or without a diversion, Pitre recognizes there will continue to be loss—of land, of culture, of language. More hurricanes will wash ashore and more land will vanish. People in his community will continue retreating north. Instead of giving in to feeling powerless, Pitre focuses on the one thing he can control—going out on the water every day and catching oysters.

“I’ll do what I can to keep the industry going because that's our identity,” he said. “We're losing so much culture, the French language, traditions. Fishing is one thing that I'm going to work my hardest to keep alive so that we can survive.”

An Introduction to Louisiana French

Louisiana French is a collection of varieties spoken by Native Americans, Africans, Acadians and Europeans since the 18th century.

Louisiana French is a collection of varieties spoken by Native Americans, Africans, Acadians and Europeans since the 18th century.

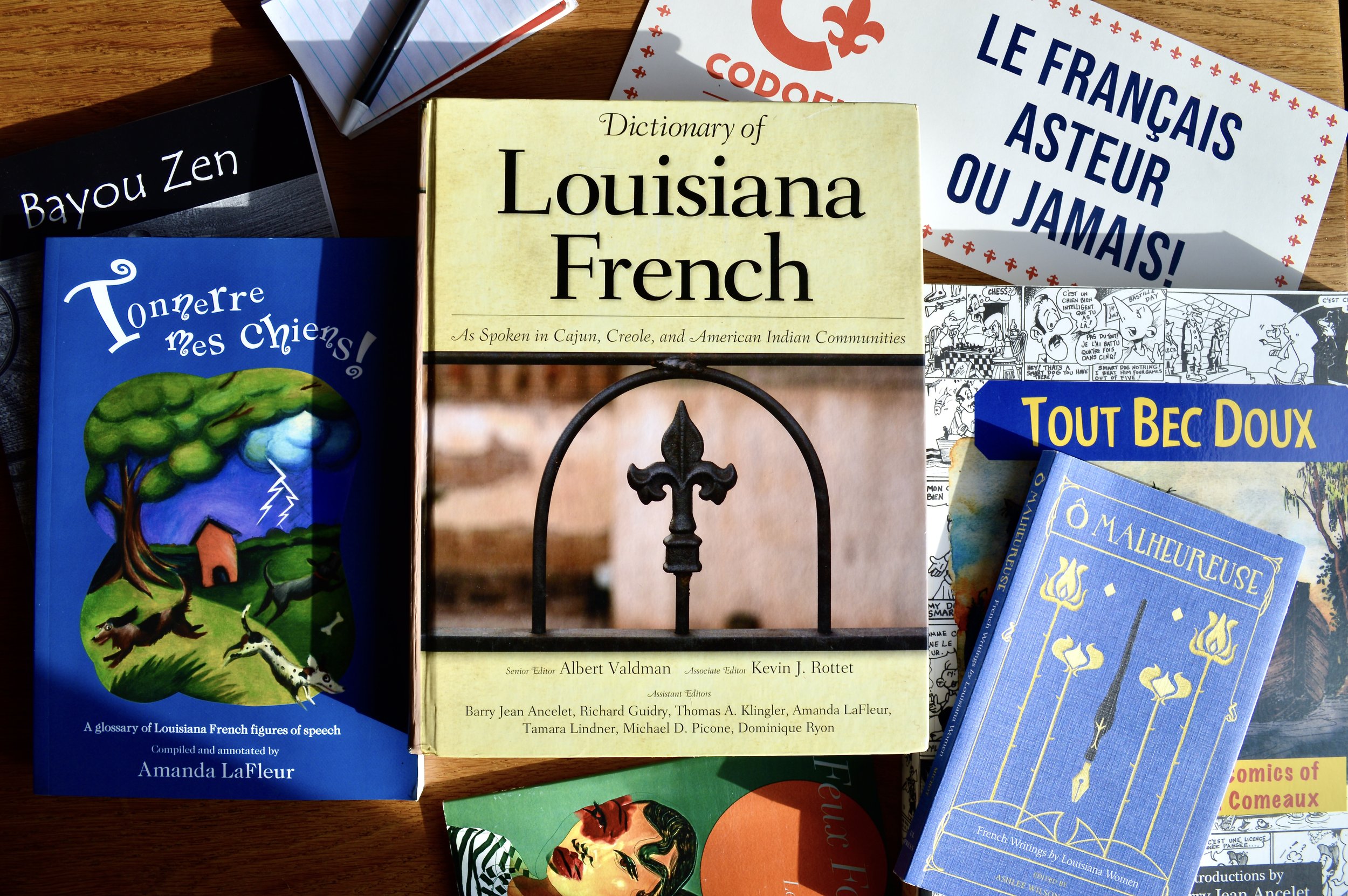

The “Dictionary of Louisiana French: As Spoken in Cajun, Creole, and American Indian Communities” serves as a valuable resource for francophones wishing to learn. Jonathan Olivier/Télé-Louisiane

By Jonathan Olivier

It was always those little phrases my mom or dad would utter that stuck with me the most. Viens manger or ferme la porte. Scattered throughout their English were words rooted in Louisiana French, the byproduct of their upbringings—their parents are native speakers of French, while my mom’s mother also grew up with Louisiana Creole.

Yet, for the majority of my life French only played a minor role—the result of decades of Americanization, economic changes in Louisiana, and the state’s 1921 constitution that allowed only English to be used in classrooms. A heritage and linguistic chain had been severed, one that linked me to my first francophone ancestors in North America who came in the 1600s to Nova Scotia, Canada, in the region they called Acadia.

The journey to reclaiming my family’s heritage language has been a long one. I have taken classes in high school, college and participated in French immersion in Canada. I traveled to Quebec and New Brunswick. I began to hardly speak English to my grandparents, embracing and better understanding the French of my family, of my home. In a region now dominated by English, I have to work at it every day. I make mistakes, then learn from them. At times, it feels more like work than reconnecting with my past. And I’d imagine this is true for most folks who have taken that step toward reclaiming a heritage language.

Although, at other points, I forget the grind and the pressure to hold on to French as the number of native speakers continues to decline. I don’t worry so much about the mistakes I make. Speaking French feels effortless. The language of my ancestors opens up doors I didn’t know were there. Ideas, opportunities and friends arrive in my life that otherwise would’ve been unknown to me. For me, speaking French has evolved past a journey of reclamation, but now it’s an integral part of my existence, a powerful piece of my identity.

For those wanting to take the first step to reconnecting with French, or even for those who are just curious about it, this guide is meant to provide you with an introduction to several aspects of it. This article is not exhaustive at all, meaning I’ve left out more than I could include. But I hope that this provides you with a start, or perhaps even inspiration to keep going in your journey to reclaim this heritage language as your own.

What is Louisiana French?

Louisiana French, also commonly called Cajun French, is an umbrella term for a collection of varieties of French that was first spoken in the region by francophone groups such as colonial French settlers, Canadians, Haitian Creoles and Acadians. French, the dominant language of Louisiana for many generations beginning in the 18th century, was also adopted by many of Louisiana’s Native American groups, enslaved Africans and free people of color, as well as German, Spanish and English immigrants.

Today, the predominant populations that continue to speak French as their first language consist of Bayou Indians (Native Americans of Lafourche and Terrebonne parishes), Creoles, and Cajuns. All three of these groups descend to varying extents from the founding peoples of Louisiana.

Over the decades, French in Louisiana was shaped by these different ethnic groups. For example, there are many indigenous elements in Louisiana’s lexicon, such as chaoui (raccoon), a Choctaw word, or plaquemine (persimmon), from an Algonquian language. The words gombo and févi (both can refer to okra) are derived from African peoples and lagniappe comes from Spanish in South America.

Other notable features are archaic structures that Louisianans have retained but that have mostly disappeared from today’s international French. For example, chevrette (shrimp) is an older French word that remained in Louisiana due to isolation while in France today people use crevette, more recently adopted from the Normans. Still, Louisianans adapted words to refer to new inventions like cars, which in Louisiana and Quebec is char and in France it is voiture.

Despite these few lexical variations, French in Louisiana is mutually intelligible with other varieties of French across the francophone world. After all, the French as it’s spoken today in France is only one dialect of the language, just as American English varieties differ slightly from British English.

A Language Continuum

In geographic areas where French has existed alongside Louisiana Creole, there is the notion of a continuum of French and its related varieties, which includes: Louisiana French, Louisiana Creole and international French. A continuum implies some sort of structure involving elements that are similar yet markedly different at the two poles. In this case, it’s easy to think about the three elements existing on a linear plane, with international French and Louisiana Creole at separate ends, then Louisiana French in the middle. These two extreme poles are different on the morphosyntactic level while there is much overlap on the lexical level between Louisiana French and Louisiana Creole. These similarities and differences are incredibly important in Louisiana, where different speech communities regularly interact with one another.

People can be placed on the continuum, depending on the language or variety of French they speak. However, due to the interaction between speech communities, people often have the ability to move back and forth along the continuum depending on who they are speaking with. For example, a French speaker might be able to move more toward Creole on the spectrum if he or she regularly interacts with Creole speakers. This tactic allows different speech communities to effectively communicate.

Although, at one time, Louisiana Creole was categorized as a dialect of French, it is in fact its own language given its unique syntax and grammar, despite its lexical similarities with French. Louisiana’s speech community is further complicated and enriched by the fact that Louisiana Creole is spoken not only by people who identify as Creole but also by many Cajuns. While Louisianans may refer to the language they speak as Cajun, Creole, Cajun French, Indian French, Houma French, Creole French, or just French, linguists increasingly use the terms Louisiana Creole or Kouri-Vini, and Louisiana French, in an effort to more accurately identify these two languages within Louisiana’s linguistic continuum.

Variations of French in Louisiana

Herb Wiltz, pictured here in episode 10 of La Veillée, speaks French and Louisiana Creole. Drake LeBlanc/Télé-Louisiane

There are several varieties of French in Louisiana that differ due to an array of factors like geographic location, age, education or even language attrition. Some francophones in southeast Louisiana, particularly in south Lafourche Parish, utilize an aspirated “h” when pronouncing “j” or “g” (j’ai été sounds like h’ai été). Someone might use the word grouiller to mean “to move” to another home, while others will say déménager or even “move,” borrowed from English. In Avoyelles and Lafourche parishes, it’s common for speakers to express “what” by saying qui while other regions of Louisiana employ quoi.

Professor emeritus at the University of Indiana Albert Valdman, in his study “Standardization or laissez-faire in linguistic revitalization,” included an example of a native speaker that, in one paragraph, used five different ways to express they, or the third person present indicative verb form: eux-autres, ça, ils, eusse, and ils with -ont.

Mais sho, eux-autres serait contents, tu les appelle ‘oir, parce que ça travaille tard, eusse a un grand jardin en arrière, et ils travaillont tard, des fois ils sont tard dans la maison. [Well sure, they would be happy, you call them and see, because they work late, they have a big garden in back, and they work late, sometimes they’re in late.]

The study displayed that different age groups tended to stick to different forms of the third person present indicative verb form. For example, 25 percent of people older than 55 tended to use ils, while only one percent of people under 30 used ils—instead, 77 percent of them opted for eusse.

Due to this variation, linguists don’t exactly have a neat definition for French in Louisiana. Instead, it’s best understood as a collection of different varieties that are spoken across the state. Even still, these varieties share a lot in common, so below are some examples that make French in Louisiana unique.

Lexical Items

Ruby and Raymond Danos, pictured here in the sixth episode of La Veillée, are from Cutoff, Louisiana, where they learned to speak French as children at home. Drake LeBlanc/Télé-Louisiane

A lexical item is a word or a sequence of words. Due to Louisiana’s linguistic diversity, its French contains some lexical items unique to the region—although much more are well known in Canada, France or throughout la francophonie. Other lexical items are quite common in French, although they have taken a different meaning in Louisiana due to its isolation from other francophone regions. Here are a few examples:

Un chaoui (indigenous origin)

English: Raccoon

International French: Un raton laveur

Asteur (common in Canada and parts of France)

English: Now

International French: Maintenant

Un char (common in Canada)

English: Car

International French: Une voiture

Une banquette

English: Sidewalk

International French: Un trottoir

Une piastre (common in Canada)

English: Dollar

International French: Un dollar

Une chevrette

English: Shrimp

International French: Une crevette

Un plaquemine (indigenous origin)

English: Persimmon

International French: Un kaki

Des souliers

English: Shoes

International French: Des chaussures

Espérer

English: To wait

International French: Attendre (in France, espérer means “to hope”)

Regional Grammatical Structure

In Louisiana, the grammatical structure, or arrangement of words, can be varied and also unique. While second language learners of French are often quick to pick up lexical items like nouns, it can be harder to incorporate more complex grammatical structures. If you talk to any native speaker of French in Louisiana, chances are you’ll hear these four structures often.

Être après

In international French, the present progressive is être en train de, such as je suis en train de faire quelque chose (I am doing something). However, in Louisiana, this form is être après, such as je suis après faire quelque chose.

Avoir pour

This is a common way to express “to have to” in Louisiana. While other ways of expressing a necessity are also common by using words such as devoir, il faut or avoir besoin, in Louisiana, avoir pour is pretty unique. For example, someone might say, J’ai pour travailler aujourd’hui (I have to work today).

Article-Preposition Contractions

With prepositions, it’s standard in international French to write and say de le as du, or de les as des. Yet, in Louisiana, you’ll often hear speakers avoid these contractions. So, one might say, C’est à cause de le froid j’ai resté dedans la maison (I stayed inside because of the cold).

Subject Pronouns

Typically, native speakers of French in Louisiana follow the same subject pronoun patterns as international French, with a few exceptions. For example, the international French vous is hardly used in Louisiana—only in very formal situations. In the below examples, conjugations that differ from international French are noted.

Je (i)

Tu (you)

Vous (you, used rarely and only in very formal situations)

Il (he)

Elle (she, sometimes pronounced/written as alle)

Nous-autres, On (we)

The more colloquial expression of “we,” expressed by on, has by and large replaced nous in Louisiana. Yet, nous-autres is often used in conjunction with on. For example, Nous-autres, on était dans le clos un tas des années passées. (We were in the fields a lot back then.)

Vous-autres (you plural)

This subject pronoun uses the same verb form as the third person singular il. For example, Vous-autres va à la messe ? (Y’all are going to mass?)

Ils (they, often used to express men and women)

Elles (they, this feminine form is not often used)

Ça, eux-autres, eusse (they)

Eusse is common in southeast Louisiana, such as in Terrebonne and Lafourche parishes. However, it isn’t as common in other parts of Louisiana. While ça and eux-autres are typically used throughout the French-speaking region of the state. These three are typically conjugated using the third person singular verb form. For example, Eux-autres a deux garçons. Mais ça voulait une tite fille itou. (They have two boys. But they wanted a little girl too.)

How to Learn

Abraham Parfait of the United Houma Nation, pictured here in the fifth episode of La Veillée, speaks what people in his community call Houma French or Indian French. Drake LeBlanc/Télé-Louisiane

There are plenty of ways to learn. Online classes taught by local experts are available, and texts that have been compiled by linguists offer valuable information about the dialect. And, of course, one of the best ways to practice is to find a native speaker to learn directly from them. If they’ll allow it, record your conversation and transcribe it, which functions as an intimate way to learn. Below, you’ll find resources to get you started on your journey to learning.

Videos

Les Adventures de Boudini et Ses Amis, a cartoon series in French, produced by Crele Cartoon Company with Télé-Louisiane for Louisiana Public Broadcasting (LPB), which is perfect for beginners or children.

La Veillée, a fifteen-minute weekly news magazine produced by Télé-Louisiane and LPB.

Le Louisianiste, Télé-Louisiane’s newest podcast with a focus on native speakers of French.

Le français louisianais: quoi c’est ça ?, a YouTube video produced by Télé-Louisiane that expains the basics of French in Louisiana.

Kirby Jambon’s French lessons, a series lessons made by Acadiana French teacher Kirby Jambon.

Classes and online databases

Classes hosted by Alliance Française de Lafayette, taught by David Cheramie and Ryan Langley.

Online resources provided by the Department of French Studies at LSU.

Louisiana French Oral Histories, an oral history project complete with interviews of native French speakers and corresponding transcriptions, compiled by the Department of French Studies at LSU.

Memories of Terrebonne, an oral history collection from Terrebonne Parish.

French Tables, which are informal gatherings where francophones get together and chat, are held around the state. This list has been compiled by the Council for the Development of French in Louisiana.

Cajun French Virtual Table Française, a Facebook group dedicated to French.

Cajun French Video Lessons, a Facebook group that posts videos.

Books

Tonnerre mes chiens! A glossary of Louisiana French by Amanda LaFleur

Dictionary of Louisiana French: As Spoken in Cajun, Creole, and American Indian Communities by Albert Valdman et. al

Cajun French Dictionary and Phrasebook by Jennifer Gipson and Clint Bruce

Sources:

Ancelet, B. J. (1988). "A perspective on teaching the “problem language” in Louisiana.” The French Review, 61,

345-356.

Ancelet, B. J. (2007). “Negotiating the mainstream: The Creoles and Cajuns in Louisiana.” The French Review,

80, 1235-1255.

Blyth, C. (1997). “The Sociolinguistic Situation of Cajun French: The Effects of Language Shift and Language

Loss.” In A. Valdman (Ed.), French and Creole in Louisiana (pp. 25-46). New York: Plenum Press.

Brown, B. (1993). “The social consequences of writing Louisiana French.” Language in Society, 22, 67-101

Dajko, Nathalie (2012). “Sociolinguistics of Ethnicity in Francophone Louisiana.” Language and Linguistics

Compass, 6, 279-295.

Dajko, Nathalie; Carmichael, Katie (2014). “But qui c’est la différence ? Discourse markers in Louisiana French:

The case of but vs. mais.” Language in Society, 43, 159-183.

Valdman, Albert (2000). "Standardization or laissez-faire in linguistic revitalization: The case of Cajun French.”

Indiana University Working Papers in Linguistics 2: The CVC of Sociolinguistics: Contact, Variation, and

Culture, 127-138.

Valdman, Albert; Picone, Michael D (2005). “La situation du français en Louisiane.” In A. Valdman et. al, Le

Français en Amérique du Nord: État présent (pp. 143-165). Les Presses de l’Université Laval.

In August, École Pointe-au-Chien to Open Kindergarten, First Grade

The board of directors convened at its first meeting on Monday, March 13, where it approved hiring two French teachers for the inaugural school year.

The board of directors convened at its first meeting on Monday, March 13, and it approved hiring two French teachers for the inaugural school year.

The board of directors of École Pointe-au-Chien voted on several measures during its first meeting on Monday, March 13. Kezia Setyawan/WWNO

By Jonathan Olivier

The board of directors of École Pointe-au-Chien, Louisiana’s newest French immersion school, located in Pointe-aux-Chênes at the crossroads of Terrebonne and Lafourche Parishes, voted to open enrollment for children seeking entry to kindergarten and first grade for the inaugural school year that will begin in August. The board also voted to recruit two French teachers in coordination with the Council for the Development of French in Louisiana and the Louisiana Department of Education.

"Not only is this going to bring a school back to our community, but it will be a beginning for bringing the language back to the community,” said Christine Verdin, council member of the Pointe-au-Chien Indian Tribe. “We will begin with elementary but will also eventually offer adult classes so interested parents can learn French too. Our goal is to hear more French in and throughout our community."

The board voted to begin soliciting interest from parents of prospective students. As permitted by applicable state law, preference in enrollment will be given to families who live in Pointe-aux-Chênes, Isle de Jean Charles or former residents who were displaced due to Hurricane Ida or relocation from the island by the state, as well as the families of former students of Pointe-aux-Chênes Elementary. If spots are still available, enrollment will then open as a lottery to students from other parts of Lafourche and Terrebonne parishes with weighting for children of French immersion teachers at the school, those with parents or grandparents from Pointe-aux-Chênes or Isle de Jean Charles, and anyone with family members with a demonstrated background or interest in Louisiana French.

Beginning with the 2023-2024 school year, École Pointe-au-Chien will be located in the Knights of Columbus building in upper Pointe-aux-Chênes. Eventually, École Pointe-au-Chien will move to the site of the former Pointe-aux-Chênes Elementary building, which closed in 2021 due to a decision by the Terrebonne Parish School Board and then was damaged by Hurricane Ida. Renovations are expected to begin on the building later this year.

“The board is working closely with the Division of Administration, the Department of Treasury, and state legislators to find the most effective ways to expend funds allocated to the school to renovate the provisional and final school buildings as well as other necessary investments in curriculum, finances, and administration,” said Will McGrew, Télé-Louisiane CEO, who was elected as interim president until the full board is appointed.

At Monday’s meeting, nine board members were present after being appointed by their respective state agencies or Indian Tribes (including the Consul General of France in Louisiana Nathalie Beras, ex officio, in an advisory capacity). In total, there will be 13 members serving on the board.

Initial funding for École Pointe-au-Chien comes from $3 million allocated by the state legislature, which voted in 2022 to pass HB 261 (Act 454), authored by Speaker Pro Tempore Tanner Magee, R-Houma, that created the school and established an independent governing board. Board members reviewed next steps for spending some portion of the $3 million by the end of the state’s fiscal year on June 30, and it is coordinating with legislators on rolling over the remaining funding to next fiscal year, which begins July 1.

The board also voted to create an online form for parents to express interest in enrolling their children who live in the target enrollment area.

“We have a lot of work ahead of us, but we are proud to be making history in creating the first French immersion school in Lafourche and Terrebonne parishes, the first immersion school serving a predominantly Native population, and the first immersion school that will teach our local Cajun and Indian French dialects of French,” McGrew said. “We are grateful for the overwhelming support from the legislature and other stakeholders in making this school a reality for Pointe-aux-Chênes and a model for communities across the state.”

Those interested in enrolling their children at École Pointe-au-Chien can complete the parent interest form or contact ecolepointeauchien@gmail.com.

La Veillée Returns to LPB for Spring Premiere on March 16

The 8-episode series explores French programming on KRVS public radio, the Isleños of Louisiana, the tradition of boucheries, and much more.

The 8-episode series explores French programming on KRVS public radio, the Isleños of Louisiana, the tradition of boucheries, and much more.

Filming for season 1.2 of La Veillée has been underway since February, featuring reporting in the field with francophones from across Louisiana. Drake LeBlanc/Télé-Louisiane

By Jonathan Olivier

La Veillée, a weekly news show produced by Télé-Louisiane with Louisiana Public Broadcasting (LPB), returns with more stories that dig deeper into the rich cultural layers of the region. The spring half of season 1 features French-language content alongside a special episode in Spanish documenting the Isleño community of Louisiana and another episode partially in Creole focused on the Louisiana Creole language.

“La Veillée is unique not only because it is in French, but also because we visit communities that are too often forgotten in mainstream coverage and we focus on stories that matter to people across Louisiana regardless of ethnic, political, or regional background,” said Télé-Louisiane CEO and co-founder Will McGrew, who is an executive producer of La Veillée.

La Veillée is the first weekly television program produced entirely in Louisiana French in over 30 years. It airs for 15-minutes on Thursdays at 7:45 p.m. on LPB and online. The spring season premiers on March 16 with a finale on May 4, featuring in-the-field reporting and interviews, and hosted by McGrew, Drake LeBlanc and Caitlin Orgeron. The eight episodes from the fall season are available online at lpb.org/laveillee.

The Thursday night premier will focus on French-language programming hosted on Acadiana’s NPR public radio affiliate KRVS. The station is home to Blake Miller’s La Lou Juke Box, Megan Brown Constantin’s Encore and Cedric Watson’s La Nation Créole.

“We have admired KRVS’s historic French programming over the years and were thrilled to see the return of Bonjour Louisiane with Ashlee Michot,” McGrew said. “Interviewing some of the young talent at the station for our spring season premiere was inspiring, informative and fun.”

Throughout the season, La Veillée episodes will explore a variety of topics:

A special Spanish-language episode focused on the Isleños of St. Bernard Parish

An episode focused on revitalization efforts underway for the Louisiana Creole language

Interviews with Lafayette-area-based musicians Jo Vidrine, Kelli Jones and Jourdan Thibodeaux

A look at the efforts to keep French alive with reports on two French immersion schools: LeBlanc Elementary, which is the first and only immersion school in Vermilion Parish, and École St. Landry, a French immersion charter school in St. Landry Parish

An exploration of the traditional boucherie through the decades-old Fête du Cochon, an annual celebration in Golden Meadow

Also airing on LPB in March is the animated cartoon series Les Aventures de Boudini et Ses Amis, created by the Creole Cartoon Company with Télé-Louisiane. Boudini premiered online in Jan. 2021, and the first season was funded with support from the Louisiana Consortium of Immersion Schools, CODOFIL, the Atchafalaya National Heritage Area, and the Louisiana Endowment for the Humanities. The move to LPB highlights the ongoing partnership between the network and Télé-Louisiane to strengthen French language programming in the state.

“Our partnership with Télé-Louisiane has been a wonderful way to share the stories of the French-speaking communities in Louisiana,” said Linda Midgett, LPB executive producer. “This has always been an important part of LPB’s mission and we are grateful for this collaboration.”

Join Millions Across the Americas to Celebrate the Mois de la Francophonie

Sylvain Lavoie of the Centre de la francophonie des Amériques discusses the importance of the francophone communities of the Americas, as well as his organization’s benefits to Louisianans.

Sylvain Lavoie of the Centre de la francophonie des Amériques discusses the importance of the francophone communities of the Americas, as well as his organization’s benefits to Louisianans.

The Centre de la francophonie des Amériques builds relationships with francophones and francophiles across the continent. Centre de la Francophonie des Amériques

This post is sponsored by the Centre de la francophonie des Amériques.

By Jonathan Olivier